Pay and Industrial Unrest

The wages of the policeman increased as he rose in rank and length of service. By the early twentieth century pay rates were often higher and always more regular and guaranteed than other unskilled working-class jobs and included important social benefits such as a pension. Yet, as in other trades and occupations, wages and conditions remained a source of disgruntlement for officers. In 1848 a number of third-class constables petitioned their superiors that their pay was not sufficient to support a family.

There was a serious situation in 1872 when over 3,000 constables and sergeants turned up for a meeting to discuss demands for a pay rise. Senior officers at Scotland Yard were so concerned that a pay rise was quickly granted. Yet the officer who acted as secretary co-ordinating officers across divisions, PC Henry Goodchild, was ordered to hand over material concerning his activities. He refused and was subsequently dismissed. In response 180 men from the 'D' (Marylebone), 'E' (Holborn) and 'T' (Kensington) Divisions refused to go on duty. They were all suspended, and 109 were sacked. Following complaints and dissatisfaction over this mass disciplinary action, the majority were reinstated but at a reduced rank, and some were fined a week's pay.

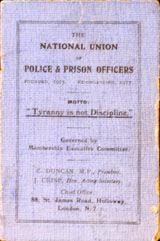

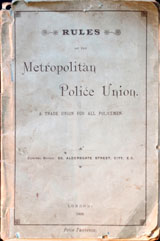

An attempt to collectivize police disaffection was made in 1890 with the attempted formation of the Metropolitan Police Union, but granting of pensions removed a major source of complaint. Since the police were used against industrial unrest the fact that officers were appropriating the language of trade unionism was viewed as a potential threat to discipline and in conflict with the demands of the job. A further attempt to unionize was made in September 1913 with the resurrection of the Metropolitan Police Union, changing its name in the following year to the National Union of Police & Prison Officers (NUPPO). Again, a glance at their membership book shows the language of trade unionism. A police order was issued in December 1913 threatening the dismissal of officers associated with the union.

Police industrial unrest reached its peak towards the end of the First World War. In 1917 police officers were removed from the list of reserved occupations – workers who were excluded from war service. To make matters worse, police pay did not keep pace with wartime inflation. The potential for conflict grew. On 27 August 1918 PC Thomas Thiel was dismissed for his union activities. NUPPO demanded that Thiel be reinstated, a war bonus to be converted into pensionable pay and recognition of the union. If the demands were not met, NUPPO would suspend its rules disallowing strike action. On 30 August almost the entire Metropolitan and City of London Police forces withdrew from duty. The unanimity of these officers took senior officers and politicians by surprise. David Lloyd George, the prime minister, agreed to increasing pay, war bonus, widows' pensions, a bonus linked to the number of children, recognition of a police organization, and the reinstatement of Thiel, as a concession for a return to duties.

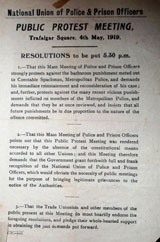

Though the prime minister stated that he could not sanction the creation of a union during wartime, NUPPO agreed, and officers were back to work on the evening of 31 August. Yet NUPPO remained unhappy at its lack of recognition. In April 1919 PC Spackman of the Metropolitan Police was dismissed for urging officers to boycott elections to the Representative Board. A mass meeting was held in Trafalgar Square in protest of Spackman's treatment. Senior officers and the government sought to crush the renewed militancy from the start.

A bill was introduced in parliament creating a Police Federation to represent the concerns of officers, though strike action remained illegal. A motion by NUPPO to call a strike in its own defence split the union. In August 1919 only 1,156 Metropolitan Police officers (in conjunction with 58 City of London men) went on strike at the union's call. The Commissioner claimed victory. All of the strikers were dismissed without reinstatement. The teeth had been removed from NUPPO. Pay increases meant that the pay of the policeman was 50 per cent higher than that of the average industrial worker, something that limited any potential for solidarity between police officers and workers. There remained, however, support for the men dismissed in 1919.

William Edward Pearce 1853-1883

William Edward Pearce 1853-1883