Heavy-Handed Policing: The Killing of Constable Culley

The module on the origins of the Metropolitan Police discusses the early hostility to the police. This was especially marked among political radicals who saw the police as agents of central government designed to suppress them and their aspirations. The first, major clash between political radicals and the police happened on the afternoon of 13 May 1833. It resulted in the death of a police constable, Robert Culley, and the knifing of two more. But the comments and verdicts of juries illustrate the problems of acceptance for the police, and suggest a serious lack of awareness on the part of the early police about how best to handle political demonstrations.

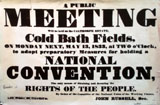

The National Union of the Working Classes were greatly disappointed by the Great Reform Act of 1832. Members of the union believed that it had not gone far enough in extending the franchise. John Russell, secretary to the union, organized a public meeting to be held at 2pm on 13 May 1833 at the Calthorpe Estate, Cold Bath Fields, Clerkenwell. Placards advertising the meeting were published a week prior to the event. Lord Melbourne, the Home Secretary, had declared the meeting illegal. The Commissioners were unsure about the legality of this and had a tense meeting with Melbourne about how best to proceed. By midday on 13 May approximately 300 people had assembled for the meeting. A heavy detachment of police was detailed to the area. The two police commissioners were present, and so were two officers from the 1st Regiment of Life Guards, in plain clothes, ready to summon a detachment of their men if the need arose.

The evidence conflicts over the number of demonstrators and police officers at Cold Bath Fields. The evidence is also unclear about how the fighting started; did the police draw their batons first, and wade into the crowd, or did they draw their batons in response to attacks? Certainly much criticism was directed against the police by the press and by people who were in the locality and witnessed the fighting. A correspondent for The Times wrote:

The police furiously attacked the multitude with their staves, felling every person indiscriminately before them; even the females did not escape the blows from their batons – men and boys were lying in every direction weltering in their blood and calling for mercy.

Two officers, Sergeant John Brooks and PC Redwood, were stabbed trying to wrest a flag from one of the demonstrators. No-one saw what happened to Culley, but he staggered into a local public house with blood pouring from a wound in his chest, and died a few moments later.

The coroner's jury that examined the death of Culley returned a verdict of 'justifiable homicide'. The jury justified its verdict on the grounds that the crowd had not been ordered to disperse under the terms of the Riot Act, and that the 'conduct of the police was ferocious, brutal, and unprovoked by the people'. A few days after the jury returned its verdict, a package arrived at the home of the jury foreman, Samuel Stockton. An anonymous donor had struck a number of pewter-type 1¾ inch medallions for Stockton, with instructions for him to pass them on to his fellow jurors. One side of the medallion contains the names of the jurors, with the message: 'We shall be recompensed, the resurrection of the just'. The reverse is inscribed: 'In honour of the men who nobly withstood the dictation of the coroner; independent, and conscientious, discharge of their duty; promoted a continued reliance upon the laws under the protection of a British jury'.

The story does not end here. George Fursey, the man charged with stabbing Brooks and Rewood was acquitted by an Old Bailey jury. On 8 July 1833, crowds thronged the streets at Blackfriars to cheer the coroner's jurors who had returned the verdict of 'justifiable homicide'. A trip was arranged by a group of City men with radical persuasions, the Milton Street Committee, for the jurors and their families to sail the Thames up to Twickenham on the steamer Endeavour. It poured with rain throughout the day, but crowds still flocked to the banks of the Thames to cheer on the jurors on their trip upstream. As the ship sailed to moor at Twickenham, canon fire saluted the arrival. The significance of the juror's verdict was remembered long after. A banquet was thrown to honour the anniversary of the jurors' findings, an event hosted by Sir Samuel St. Swithin Burden Whalley, the MP for Marylebone. Following a toast to 'The people, the only source of legitimate power', the Milton Street Committee presented the jurors with a silver cup. The inscription reads:

This cup was presented on the 20th May 1834 by the Milton Street Committee, City of London to Mr Robert French one of the seventeen jurymen who formed the memorable Calthorpe Street inquest as a perpetual memorial of their glorious verdict of “justifiable homicide” on the body of Robert Culley a policeman who was slain whilst brutally attacking the people when peaceably assembled in Calthorpe Street on the 13th May 1833.

Nearly 30 years later the verdict of the jurors was still cited in a positive fashion. On 5 March 1861 a dinner was held in honour of Samuel Stockton, the former foreman, for his work on behalf of the Benevolent Institution for the poor of St Pancras. Over forty local ratepayers attended this dinner at the Argyle Tavern where Stockton was presented with a French drawing-room clock worth twenty guineas. During a speech citing Stockton's valuable contribution to community affairs, his role as foreman of the jury at the Clerkenwell inquest was also mentioned.

The case of the unfortunate constable Culley serves as an extreme example of the problems inherent in public order policing: the difficulty for central authorities in classifying what is permissible in the streets; the legitimacy of police powers; police accountability; and the potential perils of policing.

"Mother, what did policemen do when there weren't any motors?"

"Mother, what did policemen do when there weren't any motors?"