Police Accountability

Until the establishment of the Metropolitan Police Authority in 2000 (under powers granted by the Greater London Authority Act 1999) the police in London were directly accountable to the Home Secretary. Unlike forces in the counties and provincial boroughs there was no local control and no system for hearing and discussing local needs.

The Home Secretary acted as the Metropolitan Police authority. Crucially, he had responsibility for the appointment of the Police Commissioner. The Commissioner is an officer appointed by Royal Warrant with ultimate responsibility for police operational matters, i.e. he decided how policing should be executed in practice. This is exemplified by the dictum of Sir William Harcourt (Home Secretary under Gladstone, 1880-5):

It is a matter entirely at the discretion of the Secretary of State how far the principle of responsible authority shall interfere with executive action, and the less any interference happens the better.

The Home Secretary also fixed the police rate in the metropolitan boroughs and parishes. The collection of the rates and other revenue, together with the administration of expenditure, was the task of the Receiver. At the beginning there was the suggestion that the Receiver might also be a Police Commissioner but, in the end, he remained a Finance Officer.

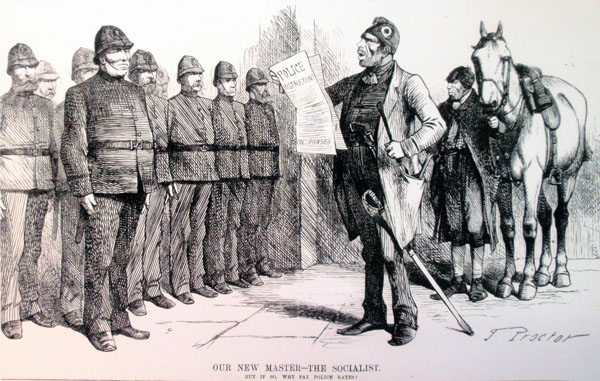

Calls for ratepayer control of Metropolitan Police received a boost when the Local Government Act of 1888 led to the creation of the London County Council (LCC) in the following year. In February 1889 a Police (Metropolis) Bill was introduced into parliament to place the police under ratepayer control, but the bill foundered. In April the LCC passed a motion, carried by a majority of 64 to 31, that control of the police should be handed over to the local authority. Opposition to these ideas was voiced on the grounds of efficiency. Since the Metropolitan Police had imperial duties in their remit, a separate police force would be needed for these duties, which could assume a military character and cost more money. There were also political concerns. The fear was also voiced that if socialists gained control of local government in London and, in turn, had control of the police, it would mean an end to 'proper' policing. This cartoon from Moonshine, 30 October 1886, is illustrative of these concerns.

A high number of complaints were brought against the police in their early years. It would appear that, by the mid-1830s, the most vocal section of public opinion, the educated middle classes, were more concerned with maintaining public order than with any assault upon liberties. Between 1831 and 1840, the average number of complaints against the police was 411 per annum. This document shows that the number of complaints was at its highest, at 511, in 1840. Of these, 273 were made against individual officers; the remainder concerned the small strength of the force and the frequency of robberies.

The police also faced adverse criticism from the press in their early days. Three such examples appeared in the Weekly Dispatch at the beginning of 1835; each was followed by a letter of explanation from a divisional officer to the commissioner. [A transcript for each of the explanations is available.]

By the 1920s formal machinery had developed for dealing with complaints. The Metropolitan Police District by then was divided into four regions, each under the control of a chief constable. The regional chief constables were a link between senior officers at Scotland Yard and the divisions. The chief constable investigated every complaint against an officer. If serious, the matter was referred to the Commissioner who decided whether criminal proceedings were warranted, or if the matter was sufficient for the attention of a discipline board. If a member of the public made a complaint, he or she, and witnesses, had a right to attend the board meeting. More serious matters were referred to the Director for Public Prosecutions. However, for the whole of 1935, only 13 officers were required to resign and another 29 dismissed for misconduct, amounting to 0.2 per cent of the force.

The complaints register for 'C' Division gives a flavour of the kind of allegations that police officers faced. 'C' (St. James’s) was a small division that covers Piccadilly and Soho, as well as other parts of the West End. 51 complaints were received for the 'C' Division between 14 January and 1 May 1935. As we can see, few officers received serious punishment. Interesting cases range from that of an unsubstantiated allegation against sergeant Hare of the CID for using a knuckle-duster (18 Jan. 1935), to that of constable Wallace (29 March 1935) who brought discredit to the force by associating with persons in connection with fun fair games (fined two days pay - £1.1.10 [£1.09]) and was severely reprimanded for dangerous driving.

However, this document is difficult to interpret. Few details are given as to the substance of the complaints. For example, on 12 April it was alleged that PC Marwick wrongly arrested a tout. A tout in this instance was a person who took bets on the street, then an offence under the 1906 Street Betting Act. Yet we will see in the module on Crime that the policing of street betting often took the form of a ritual, whereby those running the betting scams had 'fall guys' who were paid a fee by bookies to be arrested by police officers. The fall guys usually had a 'clean' criminal record so that they would not receive a heavy punishment in court. It is also well known that a number of police officers took bribes from bookmakers in order to turn a blind eye to offences, or to participate in this ritual of arresting fall guys. Is the complaint against Marwick evidence that the police weren't 'playing the game'? There is a graphic account of street betting in the memoirs of P.C. Arthur Battle.

PC giving directions to a mono-cyclist, Hammersmith, c.1935.

PC giving directions to a mono-cyclist, Hammersmith, c.1935.