Practitioners' Voices in Classical Reception Studies

ISSN 1756-5049

You are here

- Home

- Past Issues

- Issue 3 (2012)

- Craig Hamilton

Craig Hamilton

Craig Hamilton is one of Britain’s leading classical architects. He was born in 1961 in South Africa, and studied architecture at the University of Natal. He has lived in Britain since 1986. In 1991 he formed the practice Craig Hamilton Architects, which he directs together with his wife, the artist Diana Hulton. The practice specialises in progressive classical design and the repair and sensitive extension of historic buildings; their work encompasses country houses, public buildings, sacred buildings and monuments. This interview took place at Coed Mawr farm, Craig and Diana’s home in the Welsh hills, on March 23rd 2012. Interview by Jessica Hughes. All images are copyright of Craig Hamilton Architects.

- A PDF version of this interview is also available

JH. Thank you very much for inviting me to Coed Mawr to discuss your work. I’d read about the house before coming to visit, but it’s still quite overwhelming to find such a wealth of classical references in the middle of rural Wales!

CH. Yes, my ambition really was always to make a home that reflected all of one’s interests. I wanted to create something that was a world of its own, because we live in a world that is so homogenized and ugly, so coming home is like coming into a monastery. When Sandy [Alexander Stoddart, the sculptor] first came here he described it as how he imagined Odysseus’ palace to be! It’s not a conventional classical building at all. It’s quite eccentric, because the house is medieval, and then the classical bit is very much more of the Enlightenment.

JH. One of the very first things that the visitor to this house notices is the motto ‘Know Thyself’ written in ancient Greek over the classical doorway. So perhaps I can start by asking you about that.

CH. The portico was designed as a symbolic entrance that would unequivocally describe one’s belief in the classical world. It’s modelled on the Choragic monument of Thrasyllus, and it also uses some detailing from the treasury of Siphnos at Delphi. I had a wonderful professor in South Africa, Professor Barry Biermann, who was my great mentor. He was an Afrikaner, a classical scholar, and he spent his life traveling backwards and forwards to Greece and Rome, producing sketchbooks filled with recordings. I learnt that way of looking at the classical world as a practicing architect from him. And he told me of this description over the doorway at Delphi. For a visual person, it is absolutely key to know what it is that inspires you, and if you’ve grown up in a culture that denies you access to these symbols, because you’re not taught the myths and so on this can be difficult. I suddenly discovered myself when I discovered the classical world, which is why that motto was so important for me as a symbol, although it’s a universal symbol for everybody.

JH. Has South Africa left any mark on your architectural work, do you think, beyond the personal influence of Professor Biermann?

CH. I grew up in South Africa, but I haven’t been back since I left in 1986, and one of the reasons I’ve never been back is because I found love for the classical world here. But I think it does have an influence, in the sense that I grew up on farms, and I saw animals being slaughtered. The thing about classical buildings is that you realize there was a life and death aspect to it – so for instance, it is thought that the guttae on the building might represent the coagulating blood droplets from the sacrifices. Whereas in eighteenth-century English terms, that is all sanitized. And so I’m really pleased that I had that, because it gives one an earthy primitiveness that one would not necessarily get here. There is a strong English and Dutch classical tradition in South Africa, of course – and architects such as Herbert Baker contributed greatly to that tradition… But politically now the classical world couldn’t be further away from South Africa, because they are discovering their own African roots and traditions.

JH. Gavin Stamp in Apollo Magazine called you ‘one of the most sophisticated and intelligent of the so-called New Classicists’. What exactly is the ‘New Classicism’ in architecture?

CH. Well, it’s not really a cohesive movement as such. It’s really just individuals who have decided that there is still something to get out of the classical world – the Greek and Roman world – and who have gone about learning the language, and started producing buildings in the time-honored fashion. There are a growing number of practitioners in England and America doing a whole range of classically-inspired work, from the Palladian work, to others who are inspired by Greek architecture. It’s mostly Roman and Italian-inspired classicism.

JH. But within the group of contemporary architects working in the classical tradition, your work is often seen as rather different, because it isn’t so heavily influenced by Palladio, is that right?

Monument to the Prussian architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781-1841) in the 'Elysian Fields' at Coed Mawr.

CH. Yes, I think I’m fortunate in a way, in that one can come in and look with slightly fresh eyes. I am not born English, so I don’t feel hide bound by the English classical tradition – my inspiration is more the German and the Greek strain of things. Although there is a strong influence on my work at the moment by the 1920s and 1930s classical architects in England – Lutyens is the best known of all of them, but there are many others, such as Vincent. E. Harris. I share their love of a diverse range of classical references. They are a lost generation, the ones that either died in the war, or after the Second World War Modernism took hold and did its best to destroy their tradition.

JH. Your influences seem to have a very physical presence at Coed Mawr, both in the form of the objects you’ve chosen for your collection, and the architectural references that you’ve incorporated into the building. And then of course there is the memorial garden outside, where you have monuments to great classical architects – can you tell me a bit about that?

CH. Well, it’s not really a garden as such – I call it the Elysian Fields. In Denmark there is a park called Jægerspris, which is in the North of Zealand, which was designed by the sculptor Wiederwelt as a memorial garden for all the Great and the Good of Denmark. So there are monuments to bishops, artists and soldiers and each monument is more idiosyncratic than the next. They are a bit like poems - in a concentrated way they each say a little about the person they are commemorating. I have monuments to Barry Biermann and to Karl Friedrich Schinkel and others to Plecnik, Hack Kampman and Harvey Lonsdale Elmes. Diana thought it a little unnerving at first but she loves them now. I feel as though I have all these dead people beside me on the drawing board when I’m working, all the time. And it’s a comfort. One can continually refer to the way they dealt with things. Because things don’t change that much – if you’re an architect you have got to make “bricks and mortar” and put it somewhere, and the sun gets up in the East and goes down in the West! In a way the garden is a little like the precincts of the classical temples which were stuffed with votive offerings in the form of votive monuments and statues.

.png)

A memorial headstone in the North of Britain, designed in collaboration with Alexander Stoddart for a client and a friend.

The memorial pays homage to the Danish sculptor, H. E. Freund.

JH. What about inside the house? Can you give us any examples of where your great artistic heroes are represented here?

CH. Well, this room is really devoted to this particular sculptor [shows portrait], whose name is Hermann Ernst Freund. He died young, at the age of fifty-four. He was Thorvaldsen’s best pupil, who went to study with Thorvaldsen in Rome, and then went back home via Pompeii and almost singlehandedly started the craze for Pompeian decoration in Copenhagen. And he inspired his students at the Academy to design their own furniture, to make their own clothes, to paint everything. So this is his table, with the very Pompeian legs, and the anthemion in between – the little Doric order. And then the two benches either side are by his great friends who were designing sofas in the Pompeian mode, the painter George Christian Hilke and the architect Michael Gottlieb Bindesboll, who designed the Thorvaldsen museum. I’m very interested in that idea of designing everything as well, and in order to keep consistency it’s useful to have a reference like Pompeii, because everything survives, so you can see how the whole world was a unified aesthetic world.

JH. What do you think the unified aesthetic principles were, in the Roman world?

CH. Well, everything is handmade, for one thing. But also, all the references are culturally from the same source, whereas we live in a world where the German idea of Gesamtkunstwerk in architecture has been more or less abandoned. We work with interior designers who will decorate a classical house with influences from so many other cultures and yet ignore the classical culture that produced the architecture which they are decorating… And there’s a sense of order that goes out of life when you become so chaotic in your references. Whereas if you can keep them all consistent, I think it gives gravity and a stillness to architecture.

JH. As well as drawing on later classical traditions, do you also find yourself going back to the Greek and Roman monuments themselves for inspiration?

CH. Absolutely. One is always going back to Athens, and to Delphi, and to Bassae. And in a way, that’s the most purifying – it’s the only way to describe it. Because it strips away the layering of other people’s ideas, and takes you right back. Seeing buildings from antiquity…it’s shocking, the scale of them. The physical feeling that you get, standing in front of the temples at Paestum, for instance – it’s unlike anything else that you could possibly imagine. They’re like elephants in the landscape, with their scale, and their abstract qualities. I find them endlessly mysterious.

JH. Do you have a favourite ancient building, one to which you return again and again?

CH. I suppose from antiquity it would have to be the temple of Apollo Epikouros at Bassae, because of its extraordinary qualities on every level. It is a building of the most extraordinary invention, and intricacy, and sophistication, and it’s in the middle of nowhere. The fact that it is so remote, the fact that it is so sophisticated, even though it is so remote…. The challenges must have been so great, to produce something of that quality at such high altitude, so far away from civilized Athens. And the inventiveness of the building – I don’t mean that in the modern sense of ‘it came from nothing’ – I mean that it came out of five hundred years of endeavour, but one particular man and his group of followers were able to produce a building of such extraordinary…at once familiar, but at the same time entirely fresh in its approach. And even though one hasn’t experienced it because its roof is off, all that remains is sufficient to give one a feeling of how it could be.

JH. I remember now that as we passed through the entrance hall you mentioned that the Ionic column in the middle was inspired by Iktinos’ centrally-placed column at Bassae?

Corinthian column in the entrance hall at Coed Mawr

CH. Yes, that column is so important to me because it represents what I call progressive classical architecture. Iktinos was an architect who broke the stringent rules - he invented an entirely new Ionic order, which is engaged to the wall, with volutes on all four sides rather than just on two sides and what is more, he invented the first Corinthian column that we know of and placed it centrally in the temple where you would expect the statue of the deity to be placed. And through the centuries there are architects who have been not so wedded to doctrine, who were able to think outside the dogmatic rules of classical architecture, so this is why it’s so important for me. Cockerell is one of those architects – he is described as a synthetic architect because he was able to synthesize the works of the Romans, and of the Greeks and of the Renaissance, and put these influences together to make a new language. And it’s these architects that are my great heroes.

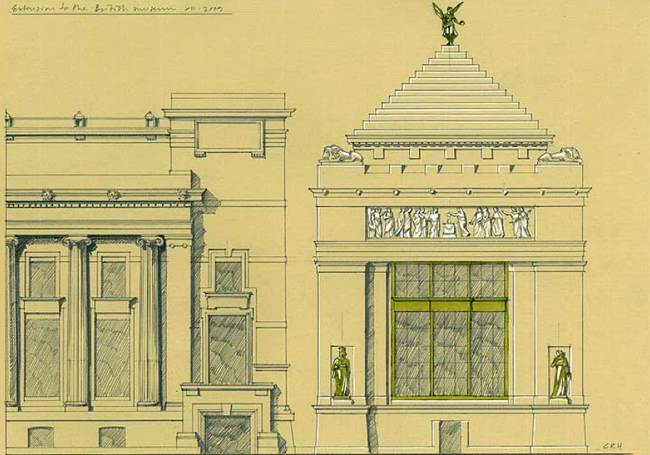

JH. I’m very keen to hear more from you about the relationship between classical architects and the modernists. I saw a drawing that you had made for the British Museum, of a monument representing the victory over Modernism.

CH. Ah, you saw that! We are at war, I’m afraid, however one dresses it up. We [classical architects] don’t get the opportunity to design hospitals or schools or public buildings. One can’t die in a classical building anymore. My grandfather died in a classical building, and I would want to die in a classical building, because I know that the experience of dying would be better in a classical building than in a modern building, because I’d be surrounded by friends – all the symbols of the world that one loves. So one does feel very much that one is excluded. The Royal Institute of British Architects, for example, only just about tolerate us. We are marginalized. So we have to be fierce about it. In spirit one has to be fierce about it, because it matters.

JH. When you say marginalized, who is that by? Is it by the people who are making the decisions about what buildings to make?

CH. Yes indeed. Since the war, there has been a misunderstanding that we couldn’t afford classical buildings anymore, that they were too expensive to build, but when you look at something like the Millenium Dome, which cost fifty million pounds – well you could get a great classical building for fifty million that would stand there for the next thousand years. And when you got tired of it being a library, it could convert into a school, or something else useful.

JH. So would you say that classical buildings are unfashionable today?

CH. Classical architecture went out of favour after the Second World War, I think, largely because the dictators employed classical architects and so it had those associations. Which was very convenient for the modernists, who were seeking ways of killing it off once and for all. So the moment that anybody suggested doing a classical building they said, ‘You can’t possibly do that, because Speer made classical buildings’ or ‘Piacentini made classical buildings’. They couldn’t separate out the quality of the buildings from the ideology. I think that had a very serious negative effect on the continuation of classical architecture. So in England, the landed gentry have been the people who have kept the tradition alive with their country houses, but the institutions – the hospitals – all of the public buildings are now in the hands of the modernists. At one time all our public squares were classical in inspiration, and they were designed to last forever. Now it’s regarded as being pompous, as being out of touch with reality. But I think it’s quite the reverse. All of the lessons from history tell us otherwise. It’ll change, but perhaps not in my lifetime.

JH Figurative imagery plays an integral role in your buildings, and you work very closely with the sculptor Sandy Stoddart. Can you talk a bit about what you see as the relationship between sculpture and architecture?

An alternative design for the proposed extension to J.J.Burnett's King Edward VII building at the British Museum.

CH. Quite often architects and sculptors work together in tandem. So Iktinos had Phidias, Schinkel had Rauch, and Sandy and I work in that same manner. He gets involved right at the beginning of the design of the building, so that the narrative – what we call the ‘architecture parlante’, the ‘speaking architecture’ develops out of the collaboration. Classical antiquity regarded sculpture as the ‘voice’ of architecture. Taking away sculpture from buildings – we regard that as taking away the voice of the building.

JH. Can you explain that in more detail?

CH. Well, the simple example is the temple. The temple was dedicated to one particular god or goddess, so all the attributes of the god and goddess would be represented in the building, and all the stories and the myths associated with them. If it was Poseidon, the doorknob might well be a dolphin, or whatever. So the building starts to take on an entire narrative. And for an architect it is thrilling, because it gives you access to all these symbols that you can incorporate into floor patterns, or ceiling rosettes. It’s a whole way of thinking about buildings.

JH. Are you and Sandy working on anything together at the moment?

CH. Yes, there’s a chapel that we’ve finally got consent for. Sandy will be doing the sculpture for that. We’re also working on a bathhouse, which is inspired by the baths of antiquity. It will have a frieze of the ancient and modern gods of the sea and a central panel of Aphrodite and on the interior hopefully a little figure of Anteros, who is the brother of Eros. He’s the God of Fidelity and of Chaste Love.

JH. That’s an interesting choice, to pair Aphrodite with the figure of Chaste Love – what’s the meaning of that?

CH. The classical world that I’m interested in is a chaste classical world, compared to the Baroque world. Sandy’s much better at describing this, but…it’s about accepting gravity. A Doric temple is the epitome of the idea, because it is so completely gravity-bound – it is so monumental and static. The Baroque world is different – it is a thrusting celebration of life, really. But there is another classical world, which is about the cold acceptance of stillness. I love all the traditions, but one must ultimately know oneself, and know what one feels instinctively most comfortable about the language that one uses.

JH. Your description of the bathhouse shows very clearly how you draw on classical sources but then put them together in eclectic ways to create a new iconographic programme.

CH. Yes, when you go into a building that you haven’t seen before, and you see the reference, but it’s been put together in a way that is completely fresh. For me, that’s the most exciting thing of all. But you need to know where the reference is from, because it’s very easy to discount these things if you don’t know. Cultural referencing is so thrilling for classical architects. Without it, one feels as though one is in desert. It’s very comforting in a building to have references that go back so far, because one wants buildings to have a sense of permanence and continuity.

JH. That makes me wonder what you think about classical ruins? For many people today, Greek and Roman temples get their evocative, romantic qualities from the fact that they are broken. And in the past, ruins have sometimes been used to symbolize the end of the classical world, rather than its permanence.

CH. It’s one of those things that you are taught by the modernists when you go to the ruins, thanks to Le Corbusier, that you need to worship them as a ruin. But when you make classical buildings you wish that they could be reconstructed so that you could experience them as buildings in all their glory, with their colour, and their bronzes everywhere, and the blood dripping down from the corona – all of that. And then I think we would have a different view of the classical world.

JH. What do you think, then, about the current ‘digital archaeology’ projects, which reconstruct ancient buildings and allow you to walk through sites like the Roman forum? Projects like that have been quite controversial for some archaeologists.

The Library at Coed Mawr, seen from the Drawing Room.

CH. Anything that can explain in visual terms how remarkable the classical world really was, and how different it is actually to the surviving fragments that are there, is a good thing. But actually it’s nowhere near as successful as a full reconstruction would be. I’m all for reconstructing the Acropolis in its entirety, in situ. I think that’s what the Greeks would have wanted us to do. I don’t think they would have a romantic view of it. I think it would be great to see it in all its glory. And there are traditions in the world where you keep rebuilding temples, particularly in the East. You keep rebuilding them forever. In Japan and India many of the great classical temples are rebuilt quite frequently. Ruins also present a sort of sanitized view of the ancient world. The modernists love it because it means it is minimalist, and the architecture parlante is reduced to fragments. And when a building is in ruin it is less threatening, because it loses a great deal of its sacred qualities, in a certain sense. It loses a lot of its power – its awesome power that you were meant to experience, that was meant to make you feel humble. Can you imagine if the temple of Apollo at Bassae, with its enigmatically placed statue, was intact? Can you imagine how one would be awestruck?

JH. Well, it’s been a great privilege to talk to you and look around your house and studio today. Thank you very much for contributing to Practitioners’ Voices, and for sharing with us some of your ideas about the classical world and its influence.