Practitioners' Voices in Classical Reception Studies

ISSN 1756-5049

You are here

- Home

- Past Issues

- Issue 3 (2012)

- Richard Shirley Smith

Richard Shirley Smith

The artist Richard Shirley Smith was born in Hampstead in 1935 and was educated at Harrow School, before studying at the Slade School of Fine Art and in Rome. In the following conversation, which took place at the artist’s home and studio in Marlborough, we talk about the role that classical antiquity has played in his work, particularly his many book illustrations and paintings. Interview by Jessica Hughes. All images copyright of the artist.

- A PDF version of this interview is also available

JH. Thank you very much for inviting me to your studio to look at your work and talk about your relationship with Greek and Roman antiquity. How did you first come into contact with the Classics? Did you have a classical education in the traditional sense?

RSS. Only by doing Latin in order to get into public school and a little beyond. I’ve always been fascinated by the whole Greece and Rome thing, but I’m not a good linguist and so I didn’t go down that road. I just admired them from afar and looked at the artefacts. I did read the classical plays in translation - illustrating books is a lovely opportunity to get down to reading all of the Metamorphoses and Eclogues !

JH. It was while you were at school that you met the poet and painter David Jones, is that correct?

RSS. Yes, although he was far senior to me - at the time I was fifteen and he was fifty-five - but luckily even then I knew what was important. There were hundreds of other boys at Harrow, but only one or two of them bothered to talk to him. But that’s just the way it is, isn’t it? He fought all the way through the first war and wrote poems like In Parenthesis and Anathemata. He was the latest of all of the war poets to get going on a great poem about the war.

JH. He used a lot of classical imagery in his work too. Do you think that had an influence on you?

RSS. I’m sure it did, yes, because he was passionate about it - imagery, and lettering and the Ara Pacis - and a lot of his poems are about the classical world.

JH. Was it your meeting with him that made you want to go on and study art?

RSS. Certainly that added to it very much. But I recently found a press cutting that was done when I was a little chap of ten, when I’d won some poster competition or something. I couldn’t believe it when I read it, because it said that even then I had wanted to be an artist, and “not just an artist that copied things, but an artist who used the imagination”! I also said that my sisters were no good at art, and I got a good going-over at home for that!

JH. So when you went on to do formal art training, did antiquity play much of a role? Did you paint classical fragments, for instance?

.png)

Two Gryphons at Miletus, 2001, Acrylic on canvas, 94cm x 71cm.

RSS. Not so much until I got to Rome. At Harrow I had a very enlightened and saintly art master, Maurice Percival, who was alive to everything to do with the past, so that was a very good thing. I said a silly thing to him once: I said that “the word educare means to lead out, so when you tell us to do these things, it’s more like intrusion than education”. He said to me very sweetly, “well if you put nothing in you get nothing out!” And that’s absolutely right. More recently, Iain Bain said of my work that I have “absorbed a tradition and reinterpreted it”, which is the sort of thing that one hopes to do. Because if you haven’t absorbed anything, or if you put nothing in, nothing is going to come out that is of any use. So at school we did still lifes, and illustrated figures from plays. Although like Blake, Maurice Percival didn’t copy material things so much as ideas. He used to set up spheres, cubes and cones, and we looked at light coming onto them, and worked out how they threw their shadows from one onto another. Strangely, that doesn’t come naturally - it has to be trained. That was very different from the Slade, where we looked at things and then responded to how they appeared. We worked at the end of the antiques room, which was filled with plaster casts, and we used to do paintings of them, as well as lots of life drawings. But that was all packed up and thrown away after we left - it’s not there any more.

JH. Was it after the Slade that you went to Rome? Tell me about that experience.

RSS. Yes, I got my national service over before the Slade, which I thought was better. You wouldn’t want to spend two years traipsing about as a trained artist. I remember marching on the way to the cookhouse behind a Doctor of Music, a brilliant organist, who was clutching a potato peeler behind his back! It didn’t seem quite right, somehow. But Rome was just a huge experience. I couldn’t believe it, and we looked at everything. David Jones wrote to us about that in one of his letters. He said, “I think it’s wonderful how you both get down to your painting, engraving etc, in another land and in a land of so many natural and man made beauties. Lots of people find it impossible to work under such circumstances”. He used the word ‘exorbitant’, in the sense that artists can’t properly work outside the orbit of their firsthand experience. For instance, when Degas went to South America to stay with some relatives, he couldn’t get round to painting all those fantastic flowers. They were out of the orbit of his experience, and an artist typically can’t do that.

JH. Can you remember any particular things that had an impact on you while you were in Rome? Were you equally interested in classical and Renaissance art, for instance? Or did you feel particularly drawn to antiquity?

RSS. Well, another thing that I mentioned to David Jones that he was particularly interested in - I’m not sure why - was that when we went to Greece after Rome, Greece was simply antiquity and then the nineteenth century. But of course Italy is so different. If you go to San Clemente, you’ve got layer upon layer like a mille-feuille, starting from the mithraeum at the bottom, then an eighth-century basilica, then on top of that the Cosmati marble workers. And then you’ve got Renaissance paintings on the wall. Funnily enough, when we went to Rome for the first time it was a no-no to think about Baroque, which was extraordinary. That was in the sixties, when the Baroque was not a serious or religious art form. Romanesque was the thing then. But that we got from David Jones, and Eric Gill who he studied with. They wouldn’t have looked at Baroque - they felt that Romanesque was the religious thing. But when I went back again, later on, I took my camera and photographed the Roman Baroque. And of course the villas of the Veneto – I’ve been on four different expeditions to photograph them. But that was all going to Italy later.

JH. So there was no real sense that you were privileging the ancient over later periods of art?’’’

RSS. No, partly because I was coming from a Catholic background, and we were all involved in Catholic Rome as well.

JH. How did you work when you were there? Did you sit and sketch the sculptures and buildings?

RSS. Yes, we used sketchbooks. Photography wasn’t on. It’s hard to believe that, isn’t it? We went all the way through the Slade, and nobody ever said “Where is your camera?”! One couldn’t conceive of going to Rome without a camera now.

JH. What was your favourite thing in Rome?

Empty Tombs, 1999. Acrylic on paper, 50cm x 35cm.

RSS. It’s very hard to say. I can’t say one particular thing. We saw some wonderful things there, like the Aracoeli church. And the sculpture, of course: Bernini is a great favourite of mine, as is Piranesi.

JH. Some of your later paintings remind me a little of Piranesi – not the style, but the way in which they present ruined cities populated by people who seem to have come from another era.

RSS. Yes, that’s what happens so much in Piranesi - there’s always some wretched little person creeping around to collect things!

JH. While some of your faces look quite modern.

RSS. Yes, well they will do, won’t they, because men have an ideal of women, and the fashion just creeps in. And then later on it makes them look more twentieth-century than anything else.

Lady at Theatre, 1999. Acrylic on board, 100cm x 69cm

JH. So what did you do when you got back from Rome?

RSS. Well, that’s when the book illustrations started. Anthony Gross [the painter and etcher, who taught at the Slade] said that I definitely ought to go and see Faber and Faber and OUP. I was naturally keen on illustrating, and one thing led to another. I had four children, and I worked out that if I made fifteen pounds every week I’d get by! I was lucky because Gross had pushed me in the right direction. Then a few years later, in 1966, a friend of mine who was an art master at Marlborough arranged that I should join him there in the the Art department. That doesn’t happen now – there’d be seven hundred people going for the job. I was terribly lucky. I just came down for the weekend, and then got the job.

JH. Were you able to teach and work at the same time?

RSS. No, no, I was very busy. But I thoroughly enjoyed it. It was a lovely job, and then I had an unpaid term off in which I did the illustrations to David Burnett’s book Hero and Leander. David Burnett was a very good friend of mine who has worked with me for years. He wrote the poem and I did the illustrations, and then he got excited about the illustrations and wrote more of the poem, and so I did more illustrations. We did leapfrog, as it were!

JH. Did you have much direction from him about what to represent – which moments of the narrative to pick, for example?

RSS. No. He understood that it was much better for artists to do what they feel - you get the best that way. I picked the pieces of narrative that amused me. I basically went through his text and when things occurred to me I would note them down. And of course I had to think how they would look on the page, and where the type would go, and so on.

JH. Was Hero and Leander the first classical myth that you illustrated?

RSS. Yes, I suppose so. I have done many more over the years, including Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which I illustrated for the Folio Society. In that case I was originally just commissioned to do the cover, which showed Bernini’s Daphne, but then the production manager said “Oh, he’s into sculptures and things, so let’s not simply use reproductions of old masters inside - let’s just get him to do them all!” [Leafs through the book]. Here is Atalanta with the boar’s head.

Atalanta and the Boar, from the Metamorphoses of Ovid (detail), 1995. Acrylic on paper, 38cm x 26cm.

JH. To me, this looks like a statue in a garden. Although it’s strange because they are on the border between life and art. She looks like a statue because she is white and immobile, but not in her face – there she’s quite animated and realistic.

RSS. Yes, and I regret that. He wanted me to do statues, perhaps even broken and deconstructed statues. I missed the boat there because I was too literal, and in some cases they weren’t really statues at all. They should all have been statues - exciting statues, coming to pieces and being propped up and fragmented, and that could have been very interesting. But I didn’t realise how much scope he was giving me, so I just struggled through.

JH. But these are very imaginative – Eurydice is changing.

RSS. She’s fizzling out.

JH. So again, in terms of which scenes you picked for the Metamorphoses – was it simply the stories that grabbed your imagination?

RSS. Yes, and I also had to have them a little bit apart. I couldn’t have them all at the end, for instance. And as well as the eight colour plates there are quite a few black and whites in there too, some of which are based on classical reliefs.

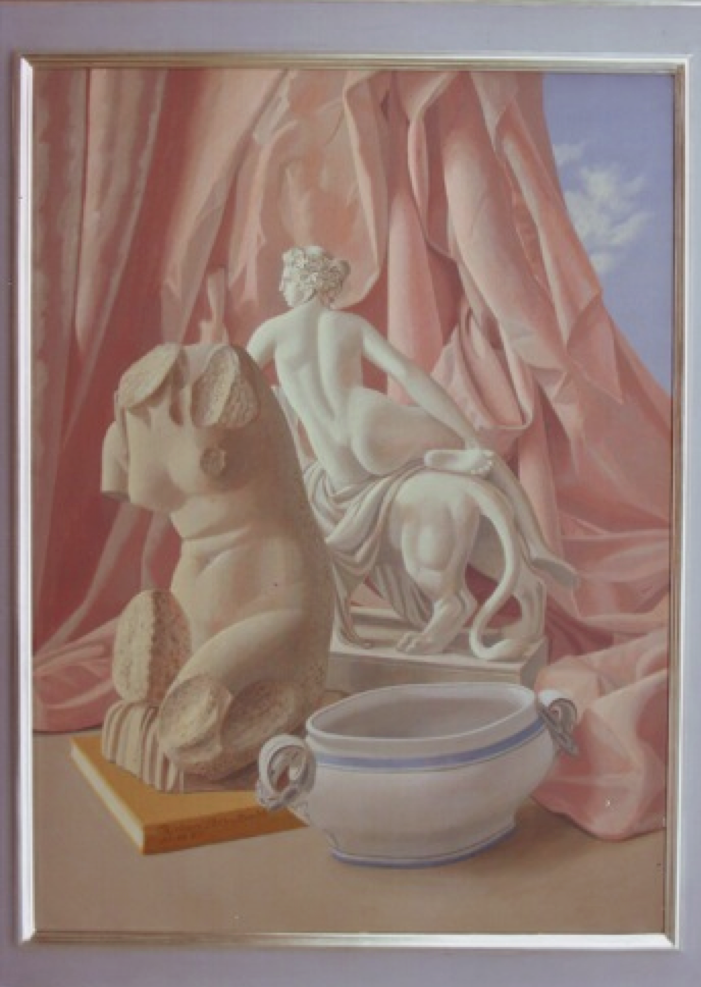

JH. Maybe we can move on to talking about your paintings now, because these are also full of classical references. [We look around the studio] The one on the wall here has got a figure at the centre that looks like those statues of the ‘Crouching Aphrodite’.

Ariadne

RSS. Ah yes, that was something that was given to me by Wilfrid Blunt [the author, brother of Anthony Blunt], after I illustrated his book Of Flowers and a Village. I went to see him when he was in charge of the Watts Gallery, and he gave me a small damaged cast. It’s in the other room - I’ll show you. It looks nice from some angles but from others it is slightly ugly because of the way that it has been hacked off. So sometimes when I use it I make it less truncated. Next to it in my studio is the skull that Rex Whistler used to have for his work. It was given to me by Simon Whistler’s widow.

JH. This picture makes it very clear how you use these classical fragments but reinterpret them, juxtaposing them with other, quite unexpected objects.

RSS. Yes, they become still life objects and get popped in with other things. So here the sculpture is together with a Victorian sugar bowl. Unfortunately it was a foolish thing to include, because it is slightly diamond-shaped. I made a rod for my back there, because however hard I worked, everyone said “That ellipse is wrong”!

JH. So your choice of artefacts to paint - is that driven primarily by issues of form and colour, or by symbolic content? I mean, are you making any particularly philosophical point through the juxtaposition of the sugar bowl and Venus here?

RSS. Oh no! It’s just a still life with different things in it. I made the background up recently, to give it more space because it was a bit flat. Although everything has it’s own symbolism, hasn’t it? In the painting next to it there’s a clock, and a doll’s head.

JH. Yes, that one is a little bit macabre!

RSS. I think it’s nice if things are a bit macabre. I only put in what I most enjoy painting. Then afterwards you might say, “Yes, that’s got a symbolism”. Surrealists wouldn’t like anyone to be deliberate about constructing symbolism. That would kill it off. It’s very different from artists like Vermeer. You’d think that he was very literal and deliberate, but his things are enormously to do with symbolism, like his painting of Fame. The painting on the wall over there is just to do with space and shadow and light. Again, I had my camera with me, and there’s a wonderful place where you can see oriental antiques, with crates from China. All the packaging and boxes are chucked to one side against wall. So I thought, there we are - I can’t afford antiques, but at least I can paint the boxes!

JH. One theme that seems to cut across all the media that you work in is the image of the classical fragment, whether this is a bit of architecture like a column, or a broken statue.... What do you think it is about fragments that captivates our imagination?

RSS. Well I suppose that’s all there is in history, when you go back. I had a little quotation from The Mikado in the recent book [Richard Shirley-Smith: The Paintings and Collages, John Murray 2002] about that: ‘There’s a fascination frantic in a ruin that’s romantic!’ But a more serious one is by David Jones in his Preface to the Anathemata. It’s in this book here. [Finds passage]. Yes, so he says “I have made a heap of all that I could find. So wrote Nennius, or whoever composed the introductory matter to Historia Brittonum. He speaks of an 'inward wound' which was caused by the fear that certain things dear to him 'should be like smoke dissipated'. Further, he says, 'not trusting my own learning, which is none at all, but partly from writings and monuments of the ancient inhabitants of Britain, partly from the annals of the Romans and the chronicles of the sacred fathers...”

That’s a more Christian view, expressed in a very learned book. It’s absolutely lovely if you hear it read.

JH. It must have been wonderful to hear David Jones read his work in person. Perhaps as a final question I can ask what you are working on at the moment?

RSS. Well, one thing that I’ve done recently that was a good bit of fun was at the Sir John Soane Museum in London. The idea was that everyone drew something related to the collection, then they had an exhibition and sold them as part of a fund-raising project. They didn’t let you write your name on them, because they had a rule that people would buy them blind. I could have picked anything, so I used the antiquities that they’d got there, but imagined them in a pile, as they were when they were found, in the midst of foliage. And I did one of Sir John Soane himself. Now I need to arrange my exhibition of new works, which is the way forward for artists. I’ve got to decide which gallery to have it in. I’ll be exhibiting all these paintings that you see around the studio and the house.

JH. That sounds very exciting! Thank you so much for talking to me about your work today.

Find out more...

The following publications contain more details of Richard Shirley Smith’s work:

Moss, R. Richard Shirley Smith: Illustrated Books, Engravings and Bookplates. Libanus Press, 2010

North Lee, B. Bookplates by Richard Shirley Smith, Fleece Press, 2005

Richard Shirley Smith: The Paintings and Collages, with a Preface by Roy Strong. John Murray Publishers Ltd, London, 2002

Bain, I. Wood Engravings of Richard Shirley Smith, Silent Books, Cambridge, 1994.

These books are all available from the artist's website, where you can also see other examples of his work.