Practitioners' Voices in Classical Reception Studies

ISSN 1756-5049

You are here

- Home

- Past Issues

- Issue 5 (2014)

- Deborah Bruce

Deborah Bruce

Deborah Bruce is a writer and director. As a writer, her first play Godchild was staged at the Hampstead Theatre in 2013, her play The Distance was shortlisted for the 2012 Susan Smith Blackburn Prize, and her play Same was written for the NT Connections Festival in 2014. She has directed many pieces of new writing for theatres across the country, including Scarborough by Fiona Evans at the Edinburgh Fringe and the Royal Court and Blame by Beatrix Campbell and Judith Jones at the Arcola Theatre, London. Deborah's new play The Distance opened at the Orange Tree Theatre, Richmond, on the 8 October. The production is directed by Charlotte Gwinner. In 2011, Deborah directed The Mysteries in the Tony Harrison adaptation at Shakespeare’s Globe, London. Two years earlier at the Globe she had directed Helen by Euripides in the Frank McGuinness version.

In this interview, recorded by Chrissy Combes at the Globe in 2013, Deborah Bruce recalls the pleasures and challenges of directing this rarely performed play.

All production photographs are reproduced with the kind permission of Keith Pattison. All captions are quotations from Euripides’ ‘Helen’ in a version by Frank McGuinness.

Links at the bottom of the page lead to audio extracts from the interview

CC. Today, I am talking to the playwright and theatre director, Deborah Bruce. Five years ago, in 2009, Deborah directed Euripides’ Helen, in a specially commissioned version by Frank McGuinness, at Shakespeare’s Globe. Deborah, hello, and thank you very much for taking time to talk to me today about your memories of directing that production.

DB. Hello Chrissy.

CC. Deborah, your production of Helen marked the debut of Greek drama at the Globe, didn’t it? I remember reading the advance publicity for the 2009 season and being thrilled and quite surprised to see Helen advertised among the Shakespeare productions of Romeo and Juliet, As You Like It, Troilus and Cressida and Love’s Labour’s Lost. And once Helen had been staged here, the show received great reviews. Indeed, Charles Spencer wrote in the Telegraph: ‘This rare revival of an undervalued classic proves the jewel in the Globe’s crown this season.’ Could I perhaps begin by asking you how you felt when Dominic Dromgoogle, the Artistic Director at the Globe, initially asked to you to come and direct this play?

DB. I felt absolutely delighted, of course. But, at the same time, I knew there were going to be challenges with this show. The first challenge was to do with the nature of casting at the Globe. The way it works. With the exception of Penny Downie who was specifically cast as Helen, Paul McGann who was cast as Menelaus, Diveen Henry who was cast as Theonoe, and Billy (William) Purefoy, the counter tenor, who I wanted as a solo singer in the chorus – all the other member of cast knew one another beforehand and I didn’t know them. Apart from those four actors I mentioned, everyone else had been in the cast of Romeo and Juliet here at the Globe, so they had been working together for a long time on that show. They had rehearsed Romeo and Juliet together and they had been performing in that production. So they all came into the rehearsal room with me knowing each other incredibly well. That is a very unusual position for a director to be in because normally, as a director, you are the one person who knows who everybody else is. But here, they all knew each other much better than I did. So it became my task to create a completely new company for Helen, incorporating the four new actors into what was really the old Romeo and Juliet company. That was one challenge and, of course, we all came together, the actors were absolutely lovely, but it could have been tricky. Then, for me, another challenge was that up to 2009 I had generally worked on new plays; I had never actually directed a Greek tragedy. Now, obviously, I did a great deal of academic research about the play before rehearsals started. But there was no way that I was going to get away with looking as if I knew what I was doing, no point in me trying to behave as if I were experienced in staging these classical plays. And I knew that from the start. So I was completely honest and I made it clear on the first day. I said: ‘We are all embarking on a new journey together here.’ So, everybody knew that I was at sea! But, in a way that was no different from the way that I would normally work on something. If you do too much planning outside the rehearsal room, if you have too strong a concept to begin with, you lose the spontaneity and input of the shared creative process, and you can fall into the trap of using your actors as puppets. So, as with everything else I have done, the production of Helen emerged as a direct result of the combination of people in that room. For instance, we did a great deal of storytelling in the room, examined the nature of storytelling; we did a lot of character work on the chorus, a lot of improvisation and movement work. The final show was testament to the work that the actors did and, of course, to the composer Claire van Kampen and the choreographer Sian Williams and the designer Gideon Davey, and many others. They all brought so much to the table. We all embarked on the journey and we all did it together.

CC. I thought that the designer, Gideon Davey, utilised the Globe space and established the setting very cleverly. In Euripides’ text, Helen’s opening speech indicates that the setting is Egypt, in front of the royal palace, with, to one side, the tomb of Proteus, King Theoclymenes’ father, the tomb where Helen has taken sanctuary from the amorous advances of Theoclymenes. The silver streamer curtain, upstage centre, conveyed the idea of the gateway to the palace interior very simply, the pillar clad in gold leaf spoke of opulence, while the mound of black earth stage right, covered with Egyptian funerary artefacts, conveyed the idea of an Egyptian grave.

‘A graveyard in Egypt before the gates of King Theoclymenes’ royal palace.’

DB. Yes. And the iconography, the two sarcophagi, and the huge black head of Anubis, who is protector of tombs and the dog associated with the afterlife, all brought the audience in to the idea of the ancient Egyptian religion and its rituals.

CC. There were several comments in the press about the Greek lettering on the upstage wall and the ramp - the word Helen, seen as back to front.

DB. Yes. Gideon’s design was so clever. Euripides’ play is all about appearance and reality, mistaken identity, doubles. Euripides takes a rare version of Helen’s story, the one that says Helen was never at Troy and that an eidolon, a phantom, went there instead. He completely reverses the accepted truth about Helen. So, by putting the letters of Helen’s name backwards, Gideon presented Helen’s alter ego. It was an inspired idea because the audience had to take a moment to think and to ask if we can ever be sure about anything for certain. They were taken straight into a theme that is central to the play.

CC. You had a great deal of pre-show onstage business with musicians sitting on the tomb, playing live music with a distinctly Egyptian mood. And, from the laughter, it was clear that the audience hugely appreciated the two painter decorators, dressed in white boiler suits, one painting the frons scenae with an extended paint roller, the other one reading the Sun while he ate his sandwiches and drank tea from a white thermos!

DB. Yes! It was only to be at the end of the production that the audience realised that these two were Castor and Pollux, Helen’s brothers, who fly in to rescue their sister from the amorous designs of King Theoclymenes. I quite liked the idea of Castor and Pollux being present and watching the action right from the start. They looked ridiculous, one was more competent than the other and one of them had a very squeaky wheelbarrow! We put in a lot of comic business around the Dioscuri. I am sure that classicists who saw the production would have frowned on this, but whereas the original Athenian audience would have accepted gods as characters, the modern audience has difficulties with that. It’s hard to play a divinity now. So I had them at the start as painters. To some extent, this was my attempt to personify God, and to suggest that maybe he is not very good at doing and being God!

CC. As soon as the bell sounded, signalling the start of the action, they exited and Penny Downie, as Helen, came rushing up the ramp and onto the stage, whooping with exuberance as she ran! I know that Euripides seemed to take a revisionist, if not a subversive approach to myth, and presented Helen of Troy in a new light in this play – but this interpretation of Helen was in a very new light, completely unexpected.

DB. Well, in this play, Helen is completely innocent of all charges against her. She curses her own beauty. She didn’t betray Menelaus, she didn’t elope with Paris, and, although she knows that she is reviled and hated for being the cause of the Trojan war, she did not cause it. She is constantly saying in this play that she never went to Troy ay all, that she is the victim of a divine plot, that she has been in enforced exile in Egypt at the hands of Hera. She is also vulnerable regarding Theoclymenes.

CC. So, Euripides gives her a completely new persona?

DB. Absolutely. And I definitely wanted to get away from the idea of Helen as a tantalising, dangerous enigma. More than anything, I wanted the audience to be able to see the girl.

‘Will you not believe your eyes? I did not go to Troy.' Penny Downie as Helen

CC. Yes. The Helen Euripides presents in this play certainly seems to be a character with youthful qualities.

DB. Oh, very much so. The traditional character of Helen of Troy, the beautiful, glamorous figure, is terribly difficult to establish because she is all about the perception of a woman from a very male point of view. She is a figure who has been greatly projected upon and, as a consequence, there is a kind of two way thing. In literature, she seems to behave in an expected way in order to serve the projection. In the investigative work into the mythology and into Homer that Penny and I did, we started with the stories about Helen’s birth, and there are reports - all written by men - about the delicacy of her ankles, even when she is only a little baby. And we were shocked by the horrific story of Theseus abducting her and raping her when she was only seven. We came to the conclusion that Helen is a woman who has been sexualised at a grotesquely early age. In other classical plays, including those written by Euripides, Helen appears as a woman who has learned that her sexuality can be used as a commodity for empowerment. Her relationship to her sexuality is a key part to her. Everything you read about Helen is about that version. However, then you get Euripides’ Helen in this one play and there is suddenly something really lovely about his portrayal of her. What he has done is really fantastic and I love Euripides for doing it. It’s as if he’s said about her ‘Right, let’s just say all that stuff isn’t true. Forget all that, and let’s find out who she really is.’ It’s a truly liberating thing to do for the character. And, gradually, in rehearsal, we were able to take all that stuff away and find something more interesting. I felt it was necessary to find the girl. I was really interested in the girl, in that almost child-like quality. This isn’t a play about young love, Helen is probably in her 50’s, and yet Euripides gives us such a charming character, warm, vivacious, playful, brimming with energy. And Penny was extraordinary, she brought a lot of her own reading in with her, her own insights, she is very hard working. She thought about every corner of that character.

CC. Might we just talk about genre for a moment? How, as a director, would you classify the play? Can it be slotted into a category? There is clearly a tragic background in terms of the Trojan war but the play has a happy ending, doesn’t it, and there are many comic elements?

DB. Well, it has a happy ending for Helen and Menelaus but it has a tragic ending for the chorus and for the sailors and for the messenger at the end. There is certainly a mixed tone and I think this is why the play is not done very much. It defies obvious categorisation. You can’t categorise it as a tragedy because in many ways it is a ridiculous story, an audience has to go on such a flight of fancy to believe it. The far-fetched elements sometimes make it hard to connect with it emotionally throughout. But, if you just looked at it as a comedy, I don’t think that would do the job either. There is a lot of comedy in it, there’s a lot of comedy to be had in it, but if you don’t take seriously the emotional content of it, that would be wrong, you would undervalue it. So, I think it has a foot in both camps, that is what I always thought about it, and my main challenge was in knowing how to pitch it. Ultimately, I wanted the audience to have tears in their eyes in the great Reconciliation scene, I wanted them to be really moved when Helen and Menelaus finally found each other. At the same time, I wanted the audience not to mind about how implausible the story really is and to laugh at other aspects.

CC. On one of the reviews of this Globe production Helen was referred to as a play with a silly story.

DB. Yes, it is a silly story and I think you have to absolutely embrace that. But so many fantastic stories are rather ludicrous and we enjoy that. It’s fundamentally silly but it’s also, fundamentally, incredibly moving. The idea of being so massively misrepresented is very serious. Being kidnapped and taken away from the life that you want to live is very serious. Being reunited with somebody that you really love after 17 years is very moving and very serious. And so within this ludicrous frame there are lots of very moving, serious issues, and that’s what’s really great about the play. But it’s also what’s really difficult about the play in that you have to find a way of being able to balance them both. You don’t want to suddenly take it terribly seriously because then you get this rather pompous, earnest production. You have to say ‘I know it’s ridiculous, and that’s fine.’ Which is why I had the Castor and Pollux ridiculousness, with the production saying ‘It’s ok, we know it’s silly, but also I am going to allow you to be moved by the reunion between these two lovers, which is really important.’

CC. So the play crosses the boundaries between comedy and tragedy. It seemed to me that, in a sense, this production of the play crossed boundaries with regard to venue as well. A play that was first performed in the Theatre of Dionysius in Athens is staged here on a resurrected Elizabethan platform stage in London. If you like, there was a kind a crossover between the great Greek classical and the great Shakespearian conventions. These stage conventions and spaces are markedly different, aren’t they? Did that present a challenge?

DB. I think if you direct a play at the Globe, you have to take the Globe space on right from the start and it was the first play I’d directed here at the Globe and it was a frightening challenge. First and foremost, I think, because you have no blackout, you have no way of making the audience invisible. What I’m used to doing is using an audience as eavesdroppers on a piece of theatre. What you now have here is 1,500 witnesses to what you’re doing and you have to absolutely incorporate them into your performance because they’re all as lit as the actors and they become part of the experience. And in that way the two venues would have been similar because they’re both in daylight, and there they all are, and you can talk to them and you have to acknowledge they’re all there. So therefore, there’s a degree of naturalism that you cannot even begin to play with as there’s no fourth wall. So that’s the first thing about this space that I think suited this play rather well. It’s about Helen wanting to say ‘Look, I’m not this person that you’re all saying I am. Listen to me!’ And no-one has been listening to her and she’s been hidden away for 17 years while all these rumours have been going about her, and the first scene is her hearing about herself from a soldier. So it’s the witnesses part of the relationship between the audience and the play that is absolutely key to the play. The truth needs to be witnessed and the frustration for her is that nobody’s heard her story. So I think the marriage between the venue and the play works particularly well here. So, yes, I completely had to take that on board.

CC. Euripides makes that witnesses aspect clear in Helen’s Prologue. And there is a comic meta-theatricality, isn’t there, in Helen addressing the audience directly? I loved the way that Penny Downie, as Helen, shinned up the ladder placed against one of the pillars, stared straight at the audience, and then blurted out ‘My name is Helen – Helen of Egypt.’ The conspiratorial charm and rueful humour with which she delivered the line drew a burst of laughter from the audience. And it was followed by an even bigger burst of laughter a few lines later when she announced ‘Zeus did it with my darling mother’!

DB. Yes, Penny took the audience into her confidence in a very engaging way right from the beginning.

'My name is Helen. Helen of Egypt.'

CC. I notice that Frank McGuinness shortens the Prologue considerably. In the original Greek and in most modern translations ‘My name is Helen’ falls a little way in to the speech, after some general explanatory background to the location and to Helen’s situation. However, Frank McGuinness puts the line first, clearly to give it more impact. He streamlines quite a lot of Euripides’ text, and simplifies many of the mythological references, doesn’t he?

DB. Oh, Frank has a very robust, anarchic style that works really well. He writes in verse but he doesn’t pretend to produce a scholarly text. His versions are vigorous, really lively, and actors love them because they have such speakability. And, with this play, I think he really connects with Euripides’ wit and makes it accessible for today’s audience.

CC. And in addition to the very pungent wit, there are some lovely verse passages in the text. This became apparent in Helen’s beautiful lamentation after the scene with Teucer.

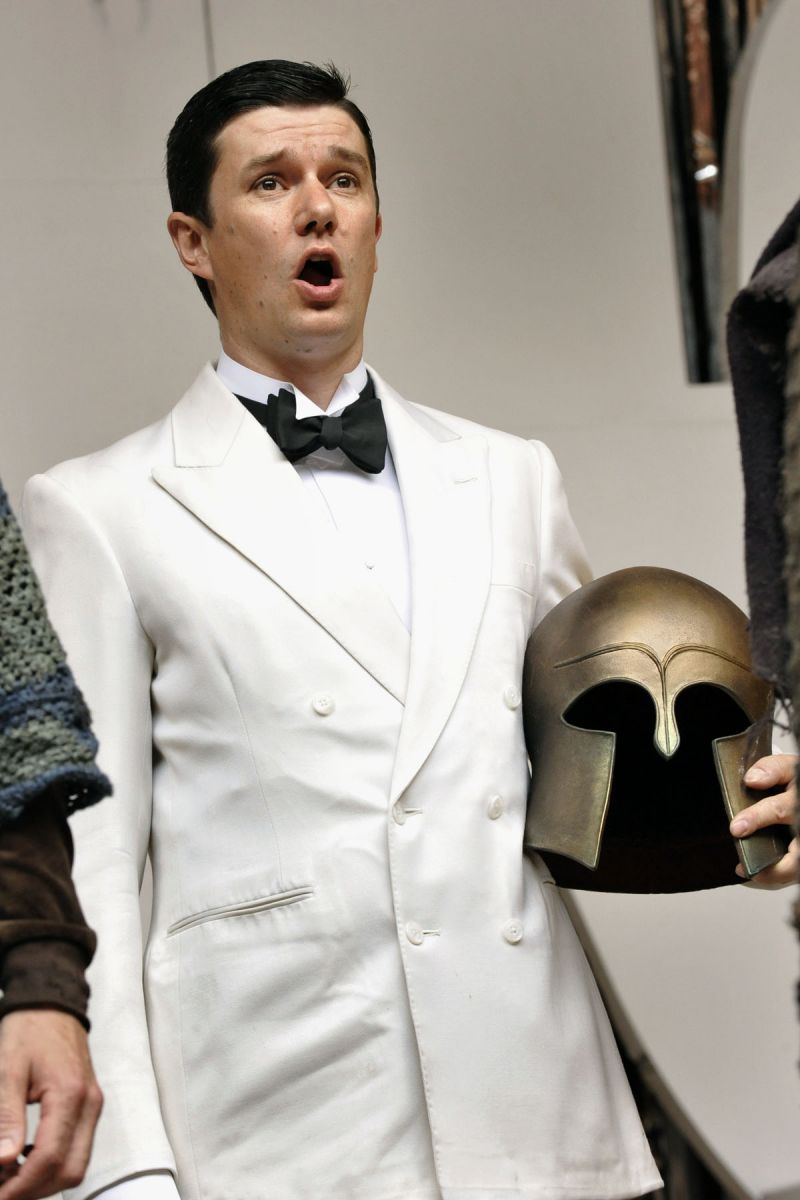

‘Teucer, Telamon’s son, born and bred Salamis.’ Andrew Vincent as Teucer

DB. That scene with Teucer is so painful for Helen. These characters don’t have full control because the gods are puppeteers over them, they have had to relinquish full control. So Penny and I worked a great deal on the fact that Helen had been hanging on for dear life for the chance to make right what had happened to her and to tell her real story to Menelaus and everyone. She has been completely cut off from Greece, from Sparta, from Troy, she has had no news, no communication about anything. And suddenly, in his brusque way, Teucer brings her the brutal details. She learns that Troy has been destroyed and that thousands upon thousands of Greeks have died on her account. Then she hears that Menelaus is believed to have drowned, that her mother, Leda, has hanged herself for shame over Helen, and that her two brothers, Castor and Pollux, are also dead, and probably because of shame about her. Helen is left with nothing in this scene. She is broken by it. Penny brought out Helen’s anguish so well, she was weeping, gasping for breath. There is a real change in tone here, a shift into a tragic note. Penny took on a tragic stature. And, as you say, after Teucer left, the lamentation was incredibly moving. As it would have been in the original performance – this is the first sung section in the play, it is almost operatic in mood.

‘Why am I weeping in pain? Who listens to my lament?’

CC. When I saw the production, I became aware of that sense of the audience as witnesses, confidential witnesses, during Helen’s lamentation. As Helen told the audience that she was blameless, they were listening intently to her testimony and sympathising with her situation.

‘My name is black, though I’m blameless.’

DB. Yes, the actor/audience dynamic at the Globe is so inclusive, the audience, especially the people standing in the yard, are in such close proximity to the actors.

CC. During that lamentation, I also fully realised how many images in this play are to do with the sea and with death brought about by drowning at sea. Helen mourns her lost husband and grieves that the sea can bring such sorrow, she weeps about ships ‘loaded with tears’. As Edith Hall emphasises in the Programme notes for this production, Euripides wrote this play in 412 BC and it was originally performed soon after the terrible disaster of the Sicilian expedition in which thousands of Athenians lost their lives at sea. Euripides surely cannot have been unaware of the emotional impact this sea imagery would have made on an audience who would have been terribly conscious of the destruction of the Athenian fleet at Sicily?

DB. I fully agree. We spoke a great deal in rehearsal about Euripides the man and about how fearless and edgy he seemed to be with regard to the original Athenian audience.

CC. I wonder if we can talk now about your choices for the chorus? I was fascinated by the fact that your chorus, the chorus of Greek slave women, consisted of five men and just one woman. Some critics thought that your decision to have a chorus which consisted mainly of men was a reference to the conventions of ancient Greek theatre, with its all male chorus. Was that the case?

DB. For me, one of the most important aspects of that production was the chorus and how to do the chorus, how to tell the chorus’ story. I felt that was a really important backdrop to the plot, a massive part of it. My decision to use mainly men was really a matter of expediency, not choice. It was about modern theatre and the way it works, rather than ancient theatre and the way that worked. As I have said before, you combine two productions at the Globe and, in this case, the same cast from Helen was in Romeo and Juliet. I had to work with Dominic (Dromgoogle) who was directing Romeo and Juliet with regard to casting, and, of course, there is not a big number of women in Romeo and Juliet and I had this chorus of women to cast. So it wasn’t a case of me saying ‘I am going to cast men as women’ it was a case of me saying ‘I’ve got to use your cast and you haven’t got any women!’ So, that is why I had one woman and the rest were men. But we did so much work with that chorus on creating female characters that I thought of them as women by the end of it. And each one of them could tell you what her journey to Egypt had been like, what she had left behind at home, and how long she had been in Egypt, enslaved. I did tons of work with them all on their back stories and on their relationship to each other. It was work that I really enjoyed on that show, with the chorus, creating those stories. And we worked hard on the chorus’ relationship with Helen. Their one link to Greece, to their homeland, is through this woman, their queen. The chorus support her totally, for instance, after their first entrance, when they have heard Helen lamenting, they comfort her, they calm her, they rock her in the lamentation. And they always stay with her. Euripides is definitely saying something about the female experience, about female solidarity, through the chorus. Their objective, their sole purpose in life, is to support Helen.

‘I heard a cry of horror. A lament, a woman singing.’

CC. Gideon Davey, the designer, emphasised the marginalised status of this chorus, didn’t he?

DB. I can explain that journey in detail, in that I didn’t know how I wanted to present the chorus, but I had this postcard that I’d had for years of a group of displaced women which I found really moving. That was the starting point that I brought to the table. And then I was walking through New Cross, which is near where I live, and there was a group walking towards me of slightly disenfranchised people. They were drinking, in the day, and were quite lost in lots of ways. And there was a woman with them who had very interesting, eclectic clothes on, she had a funny combination of clothes. She was very large and she had quite a girly A line skirt and very strappy sandals, and she had no bra on, and she had a big, very masculine top, a sort of anorak. And she had a moustache, rather oddly, I don’t quite know how that had happened, but she had a moustache, and she obviously didn’t feel great about herself. And the image of her just really stuck with me and I was really interested in that kind of look. So I worked with the designer to try and find a combination of very feminine detail and a kind of look that also lacked self esteem and lacked a sense of specificity. And anyway, he had worked very well to make the men look like women and they had wigs, originally they had wigs and a lot of stuff on their hair and they all looked terrific. But one day, in the technical rehearsal, their wigs were being worked on in the workshop, and so they came on in full costume without their wigs and everybody just went: ‘That’s it!’ And that’s why they ended up with their men’s hair, with their facial hair, with no concession to femininity about their heads, and yet they were dressed as woman, and they were women. That is how that slightly odd look came about. But when you looked at them, you believed in them as women, traumatised women, slaves in a barbarian land, far from home. And although they were a collective identity and often spoke and sang in unison, each one of them had a different story.

‘Women of Greece, foreign ships slaved you. You know the sea can bring sorrow.’

CC. How did you build those different stories with the chorus in rehearsal?

DB. Well, I am quite actor led in the way that I work. But we used photographs and images and I had the actors drawing maps of their journey to Egypt. They could all tell you their back story in great detail. And they each had a significant object in their pockets during the performances, something that tied them to their Spartan homeland. It all happened naturally, it was very organic. The hierarchy in that group of chorus was very organic. There was one actor, James Lailey, who created a very old woman who was very wise in the group and of very high status. And Holly Atkins (the one woman) was very vocal and she put herself out there, and took a lot of flak for the chorus within the action. And there was one actor who was in the chorus who did something which I really respected, actually. I hadn’t split up the choral odes before I came into rehearsals so it was up for grabs, really, who was going to say what, and it was going to be dependent on who created which kind of character. And there one actor who created a character very early on who was so damaged that she was unable to speak. And I thought that was just such a letting go of egos for an actor! His name is Philip Cumbus, and I’m just about to work with him again, in the Mysteries. He created a young girl who had been taken away from her mother when she was brought over to Egypt, and was so traumatised that she had never been able to speak since. I am sure that a chorus leader in Ancient Athens wouldn’t have been impressed by a chorus member who decided in rehearsals not to speak but it worked wonderfully within the context of our production! I loved that chorus. It was a real pleasure, working with them in that rehearsal room.

CC. Do you get a good deal of rehearsal on the Globe stage itself?

DB. No. You get just a little bit, a tiny amount of rehearsal on that stage, half an hour here and there. But I vividly remember the first time that Paul McGann, playing Menelaus, transferred to the stage. There was a tour party in. You get tour parties around when you’re rehearsing, even during the techs (technical rehearsals). The tour parties still keep coming in. You often have people in the yard. Well, Paul was on stage delivering a speech and suddenly in came the tour party. And immediately he connected with them and he just came alight. He’d been great in rehearsals but it wasn’t until that moment that I realised that he was going to be absolutely incredible as Menelaus. That’s what it’s all about at the Globe. You can’t be shy with the audience, you have to look them in the eye and include them and that’s what Paul did immediately. He was wonderful.

CC. How do you think the character of Menelaus is portrayed by Euripides in the play? The character is rather far away from the ‘glorious’ Menelaus of Homer, isn’t he?

DB. We did a lot of research on Menelaus and looked at how he is portrayed in other plays as well. He is sometimes nasty. Even Euripides makes him unpleasant in Andromache and Iphigenia at Aulis. He’s different in Helen. He is less of the soldier, in this play. But my main feeling about him in Helen is that he is neither weak nor strong, he is just very human, a very human character. He is weary and bewildered and disorientated and absolutely ready to give up when we first meet him. Who wouldn’t be, after the endless travelling at sea, travelling for seven years because the wind wasn’t in his favour, and then enduring the shipwreck? Not to mention that he has been publicly cuckolded, humiliated for years and years. He has probably suffered through all these years with people taunting him about his own wife. And here he is now in rags. He’s sunk very low.

‘I do not know this place or its people. Don’t ask why I parade in filthy rags.’ Paul McGann as Menelaus

CC. One school of thought suggests that Euripides strips Menelaus of heroic qualities in this play because the playwright was himself cynical about heroes in light of the miseries caused by the long drawn out Peloponnesian war and the annihilation of the Athenian fleet in Sicily. Do you think that might be true?

DB. Possibly. Euripides certainly brings his own take to the character. And I certainly think Menelaus is not a natural warrior in this play. And there’s the joke, isn’t there, that Menelaus is not very bright, that he has more brawn than brain. And Frank (McGuinness) really plays with that, makes him very slow and not ‘getting it.’ In fact, one day when we were rehearsing the ‘Menelaus in rags’ scene, Frank said to us that actually, when he first appears, Menelaus hasn’t even got much in the way of brawn!

CC. Well no, he even breaks down and actually weeps when the Gatekeeper appears, doesn’t he?

DB. Well, the Gatekeeper is so rude to him to begin with. She has no idea that he is a great soldier or a leader of men, and wouldn’t care less if she did know. That scene with her, where she addresses him so abusively, is Menelaus’s final humiliation. He feels completely divested of his former high status. He’s at rock bottom, really.

'What's the racket? Away from here, hop it!' Penny Layden as the Gatekeeper

CC. You had a much younger Gatekeeper than is usual!

DB. Oh yes, Penny (Layden). She always brought a wonderful energy onstage with her.

CC. And when Helen re-enters two minutes later and Menelaus sees her, he is utterly bewildered. He wants to believe that this vision is his wife but he cannot grasp the situation. Helen, of course, recognises Menelaus very quickly, after her initial recoil from his ragged appearance, doesn’t she?

'Who are you?'

'Your wife's opening her arms. Why aren't you running into them?'

DB. Yes, but the fact that Menelaus doesn’t get it here, you can’t blame him for that. He is traumatised and the whole scenario about the phantom is so hard to believe. You could say that the fact he doesn’t get it at first is not stupid but quite sensible, given the circumstances.

CC. When the Old Servant came on in your production and the full mutual recognition between Menelaus and Helen finally occurred, the scene was very touching indeed. You saw and believed in the couple’s joy; this was beautifully conveyed by both actors.

‘This is the day I’ve longed for. I take my wife in my two arms.’

DB. That is the effect on the audience that I wanted. This is an extremely famous recognition and reconciliation scene – and Euripides has made it very moving. This couple have endured a long, tragic separation, but they have remained deeply in love. They have a tender relationship. So I wanted the scene to be a really magical moment and that is what we had worked for in rehearsal. But also, the thing that the Globe space gives you, the scale of the space is so interesting. When two people are very close on that massive stage, it feels amazing, because you’ve had to achieve so much distance in other parts of the action. It’s funny, because the rehearsal rooms here, none of them are as big as the space. So you don’t really get a sense of the space until you are actually in it. And, of course, the other things the rehearsal rooms have are ceilings. So when you take the ceiling off the space, it’s enormous. So, if I am rehearsing a scene in here, and I put an actor over by the fridge and another by the door, having a conversation, you think it’s stupid, they’re so far away from one another, it’s never going to work. But, actually, because the scale of the Globe is so big, you can have two people on opposite sides of the stage, having an intimate conversation, and you believe it. And then, when they walk from that position towards each other, it’s sort of amazing, because it feels as if they were already having a conversation at that distance, so that’s a proper closeness, suddenly. You need to use it as a valuable currency, closeness on that stage. So when you have two people running into each other’s arms, it has a real electricity about it. Added to that, Penny and Paul were a great couple, brilliant. Both of them responded so well to that stage. And both of them have a kind of transparency which is really lovely. They gave a lightness and a beauty to that relationship which was really appealing. There was such a sweetness in this reunion, made even more poignant because this isn’t a play about young lovers, it is about two older people who have endured, who have suffered, and who suddenly find great happiness.

'Look, friends, my happiness - my husband.' Jack Farthing (Chorus member) looks on

CC. This must have been a very different scene in the original performance of the play in ancient Athens, do you think?

DB. Oh yes, it would have been very much more stylised, both actors would have been men, they would have been wearing masks. But it would still have been a beautiful scene at the centre of the play, with considerable emotional impact. I am sure that is what Euripides intended.

CC. I am glad that you refer to Euripides’ intentions, because I would be interested to hear your thoughts on what impact he might have been aiming for with regard to the Old Servant in this play, the Old Servant who is staggered by the realisation that Helen was never at Troy at all, and that therefore the Trojan war had been fought for nothing, With this scene in mind, Michael Billington, in his review of your production (Guardian), commented that Euripides’ scepticism is unmissable. Do you think that is the case?

DB. Undoubtedly. For me, Euripides was certainly making an ironic, savage, brave political point. The original Athenian audience, when they heard these words (in the original Greek, of course) could not have failed to register the implication that the terrible Sicilian expedition had been undertaken for nothing as well. Euripides is making a bitter comment on war, and on war’s ultimate absurdity.

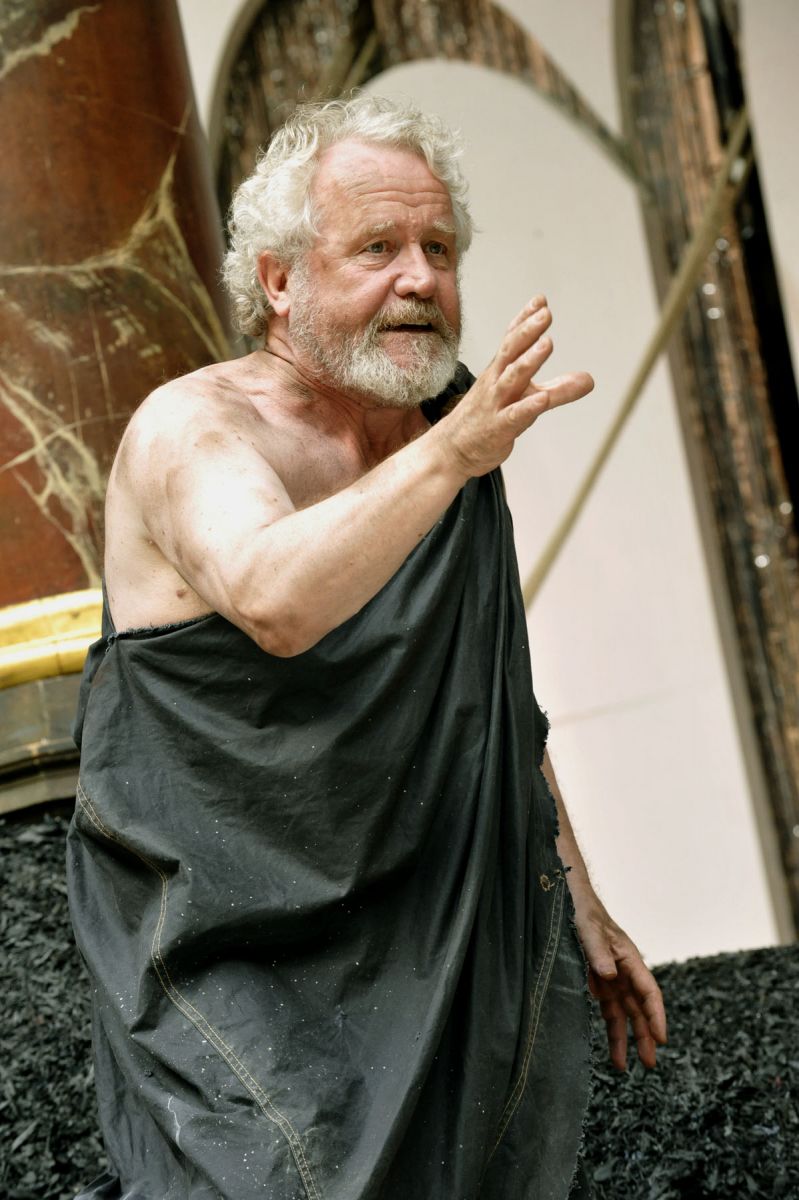

'The war was for nothing? We endured all we endured – We fought for something that never was?' Ian Redford as the Old Servant

CC. There was a biting topical relevance in the Old Servant’s words which certainly made a great impact on the audiences at the Globe in 2009. Indeed, the words seemed to prompt some quite dangerous performative moments. When I saw your production for the second time, there was a burst of cynical laughter when the Old Servant, utterly bemused, commented that the war had been for nothing. Then, when he said that the war had been fought for an illusion, there was general angry muttering and a man sitting next to me called out ‘weapons of mass destruction!’ Did you foresee this kind of bitter contemporary reaction when the company was rehearsing the play?

‘We all saw a city ripped asunder, Men breathing their last for the sake of what? An illusion, a dream – nothing, nothing’.

DB. Oh yes, everyone was very conscious of the Iraq war, its morality, its aftermath, we spoke about it a lot in rehearsal. This is what the greatest classical plays always do, they connect with our modern consciousness and circumstances. I was embarking on a journey with a group of actors in 2009. The play was inevitably going to connect with 2009. We all bring something to the work that we do and if you create a piece of work that is ensemble created in the room, it will be relevant to the world we are living in and to the audience living in that world. A great text will connect with the audience, whether you try and update it, whether you put it in modern dress, or any of those things, that’s entirely up to the individual director. Each age has its own story but war and the destruction it brings are universal, connected through time. So, through the production of this play at the Globe at that time you had the Trojan war and the Peloponnesian war and the Iraq war all linked. And the audience understood. Whether you are chasing Helen, chasing Sicily, chasing Saddam, war is always pointless and it always brings misery and death. And we didn’t have to seek ways to make this play relevant, to emphasise its political purpose, its darker resonances. Euripides had done that for us.

CC. Euripides certainly seems to be subtly subverting Athenian notions of patriotic, civic identity in Helen. Do you think, in his portrayal of Helen and Menelaus, he is also subverting the status quo, the accepted Athenian norms regarding women? Is he manipulating the gender roles by making Helen more quick witted, more intelligent than her husband? For instance, she is the one who initiates their plan to escape from Egypt and from the very real danger in the shape of Theoclymenes. She seems to take the initiative in everything.

‘Do I really hold you to me?’

DB. Oh, Helen is the one who is the absolute force to be reckoned with. There is no doubt about that. Yes, she initiates everything. She is by no means the traditional wanton Helen in this play but she is sexual, she loves him physically and she shows it first. And she is intellectually superior (although she tries not to let Menelaus know that she is). She has great initiative and logical thought processes and the power to think and plan incredibly fast. When they are making the escape plan, he is just grasping at rather silly machismo unrealistic ideas while Helen sees exactly what they have to do, she sees a practical way out. And Menelaus has to bow to her judgement.

‘Listen – do you trust a woman’s wit?'

CC. But I was interested that Charles Spencer (Telegraph) wrote in his review: ‘Paul McGann beautifully captures the wonder of a battered old cuckold unexpectedly recovering both his love and his dignity.’ Do you think that Menelaus recovers his dignity and his heroic status once the escape plan is under way?

DB. Oh definitely And this is all to do with him putting on armour again and getting rid of his rags. Once Helen has thrown away Menelaus’ castaway clothes and dressed him in armour he becomes the warrior, the soldier, once again. And the Messenger at the end of the play relates how bravely Menelaus fights the Egyptian sailors on board the escape ship. Yes, Euripides gives Menelaus back his heroic status. Once he has his armour back on he is again one of the heroes who conquered Troy.

‘Let me hold my head high once more.’

CC. Which brings us back to the themes of appearance and reality which are so evident in this play. Euripides is known to have been a friend of Socrates and a dramatist who was drawn to philosophical and intellectual thought. Sometimes Helen seems to be very much a drama of ideas. Seeing your production really made me realise how much Euripides is exploring questions of identity, ideas of reversal, of the nature of opposites.

DB. Reversal, yes. For instance, Helen has become a wife again at last, but in order to escape, she cuts her hair, goes into mourning and pretends to Theoclymenes that she is a widow.

‘Menelaus – Menelaus has died.’

CC. And Euripides seems to play with the idea of doubles.

DB. Yes, you certainly see doubles everywhere. There is Helen herself and the phantom Helen. Then Castor and Pollux are twins, and Theonoe and Theoclymenes are also twins. And you can see the idea of opposition in the depiction of the Egyptian brother and sister. Theoclymenes is dangerous but if you look at Theonoe, she is a wise, holy prophetess who everyone respects and who agrees to help Helen and Menelaus.

‘I wish to breathe the air of heaven.’ Diveen Henry as Theonoe

CC. Whereas, Euripides makes Theoclymenes into more of a melodramatic role, doesn’t he?

‘I’ll have my revenge!’ Rawiri Paratene as Theoclymenes

DB. Well, that is what I thought at first, and Theoclymenes might well have been played as a typical barbarian villain in the ancient theatre, I don’t know, he probably was. But we looked at that role in the rehearsal room, examined his back story, and actually ended up with quite a different view of Theoclymenes. The psychology of his character is really interesting. He’s had this brilliant father, King Proteus, who everyone has absolutely adored. And then he has a sister who has mystical powers, is good and loved, makes all the right choices, and knows everything. What a nightmare! How could you be a nice bloke? How could you be a good man with all that to live up to? I really liked that character. I really felt for him. And I thought it was important that he be cut some slack. So, although he is in many ways a comic character, I wanted the audience to have some sympathy for him. After all, Theoclymenes shows dignity at the end of the play.

CC. There was plenty of knockabout comedy in the appearance of the Dioscuri at the end, when they arrived to save the day, protect Theonoe from Theoclymenes, and ensure that Helen departed safely. It is probable that in the original performance of the play in the Theatre of Dionysius, Castor and Pollux would have made their appearance on the crane. In your production, the Dioscuri made rather a different airborne entrance! The two painters originally seen in the pre-show sequence, with feathery angels’ wings attached to their white dungarees, were flown down from the musicians’ gallery, and Pollux became horribly tangled up in his harness!

‘We are the Dioscuri’ Fergal McElherron (behind) and James Lailey

DB. I know. I know. I am sure that academics would not have approved of the interpretation! And, I suppose for the ancient Athenians, the appearance of the Dioscuri would have had much more religious significance. Although I think Euripides was a bit of a radical when it came to religious thought. But that Deus ex Machina appearance is so strange, truly so clumsy and contrived. How could you do it without comic business, how could you do it otherwise today? I honestly think it’s almost as if Euripides was in a rush at the end and couldn’t think of how to finish the play! I was happy to tease the idea of Castor and Pollux with human attributes and in a relationship where one is doing all the work and is really exasperated with the other because he isn’t doing any. I don’t think it is too far-fetched to give the gods human attributes in this play. After all, jealousy is at the heart of Hera’s treatment of Helen after the Judgement of Paris, and that is an all too human characteristic.

CC. And in the middle of this comic finale to the play, there were poignant moments. In your production, the sadness of the chorus as they realised that Helen was abandoning them was very moving to see. Their longing for home, for Greece, for their families was made so palpable.

‘I call to mind a sea free as the wind. I call to mind my Greece, my kith, my kin.'

DB. Yes. They have been Helen’s confidantes all through her exile and she leaves them behind in Egypt with only a vague kind of promise that she will eventually come back for them. Helen’s past suffering has taught her that she has to look after herself, to put herself first. This is an aspect of Helen that isn’t entirely likeable – her experience and her hardships have made her very self centred, but she has learned that she has to behave in a certain way in order to survive. She has one chance to escape so she just grabs that chance. But her leaving of the chorus is significant. These women have dedicated their lives to supporting her. She sacrifices those women. She leaves them behind in Egypt.

CC. You had a great deal of ritualised choreographed movement in the chorus, which was extremely effective. I noticed this particularly in the famous Nightingale ode, which was greatly reduced from the original by Frank McGuinness, but was very beautiful and still a poignant indictment of war and the suffering it brings, particularly to women.

DB. Oh, we had a wonderful choreographer in Sian Williams. She is absolutely brilliant. The most important thing about her is that she makes people feel as if they can move when they think they can’t. Somehow, within minutes, Sian allows people to find a way of doing really wonderful things. And that was very important for the delivery of the choral odes, which, as we know, would have been choreographed in ancient performance, they would have been delivered in a choreographed formation.

CC. And in a stylised musical mode, which you had as well. Particularly with the contribution of the counter-tenor leading the chorus. His singing had a wistful, ethereal beauty.

‘I call on the sorrowful nightingale.' William Purefoy as the Singer

DB. Oh Billy’s voice is beautiful. And I worked from very early on with Claire van Kampen who composed the music. I know that music is really important in that space at the Globe. Music so often makes us engage with our hearts and not our heads. It was a really significant part of the storytelling and it hugely enhanced the mood, especially in the sadder moments of the play.

CC. I’d like to ask you one final question, Deborah. It concerns Euripides and his stance on women. There are widely differing views on Euripides and the woman question. He’s been called a misogynist, he’s been called a ‘post feminist’. He often depicts very dominant women, such as Medea and Hecuba. But how do you think he feels about Helen? Is he on the side of Helen?

DB. Oh absolutely. I think the fact that he’s written a play that says ‘Let’s say that all of that isn’t true’ is a massively generous thing to Helen. Yes, absolutely. And I think that one of the things that Frank said to me – and this is when I was coming at it from knowing absolutely nothing – one of the things that really delighted him about the Greek theatre and these writers, he just said ‘They know everything.’ It’s thousands of years before modern psychology or psychology as a science and all these things that we think we know all about and we understand because we know Freud. Frank said ‘They just know everything, they kind of implicitly know it all already.’ I can’t speak about Euripides’ work as a whole. It’s still not my area of expertise. But I think this is a very generous play to Helen. I think it’s a gift.

CC. Let’s finish on that lovely thought –that this play is Euripides’ gift to Helen. Deborah, thank you for sharing your memories about your production of the play. It has been fascinating to talk to you.

'I'm afraid there is no Helen of Troy.'