Practitioners' Voices in Classical Reception Studies

ISSN 1756-5049

You are here

- Home

- Past Issues

- Issue 7 (2016)

- Umberto Passeretti

Umberto Passeretti

Umberto Michele Passeretti was born in Rome in 1945, and spent his early years living at the site of Hadrian’s Villa. In his twenties he studied at the Ecole Supérieure des Beaux Arts in Paris, before returning to live and work in Rome. He was part of the Nuova Scuola Italiana di Parigi, together with Sergio Birga, Andrea Grassi and Vito Tongiani. His paintings have been shown at international venues including the Grand Palais and the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris, and at the Museums of Modern Art in Tokyo and in Osaka. His latest retrospective exhibition, Un Presente Antichissimo (‘A Very Ancient Present’), was held at Trajan’s Markets in Rome from December 2015 until April 2016.

Jessica Hughes met Umberto Passeretti at Trajan's Markets on March 16th 2016. Interview translated by Jessica Hughes.

All images copyright of the artist.

JH. Umberto Passeretti, thank you very much for meeting me. Your work is very wide-ranging in style, but you are perhaps best known for paintings like these ones we’re seeing today, which strongly hark back to the forms and ideas of classical antiquity. How long have you been working with classical material, would you say?

UP. Oh for at least thirty years now. I actually grew up in Hadrian’s Villa, did you know that? I was incredibly lucky! My sister ran a tourist village which had been built in 1960, and I lived right next to the Canopus – literally ten or twenty metres away from it. I saw all the most important excavations being done there. I did go to Paris in my twenties, and I studied there for four years. But after ‘68 I came back here to Italy, to the town of Villa Adriana.

Strangely enough I only started reaching back to the past when I had left Villa Adriana to go to Paris. I caught this ‘virus’ for antiquity. The ancient world is so essential, so beautiful. It’s just perfect. But even then there was a delay before I started painting the classical figures, because in Paris everything was moving towards the events of ‘68, and my work at that point was very different.

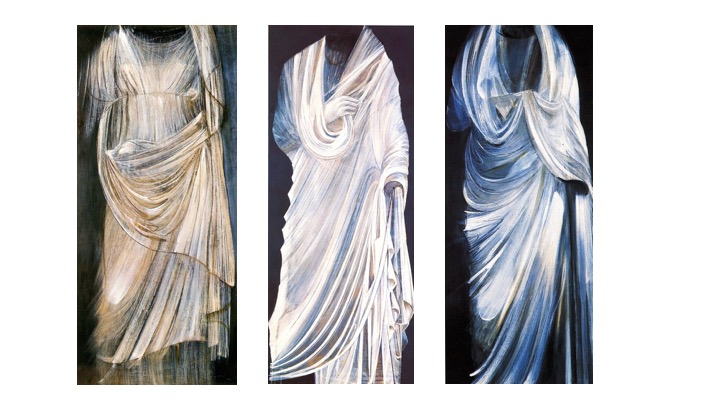

(Left) Virgo, 1985. Oil on wood. 150 x 70 cm.

(Centre) Homoquidam, 1986. Oil on wood. 150 x 60 cm.

(Right) Mater, 1986. Oil on wood. 140 x 66 cm.

JH. We’re standing right now in front of one of the very first paintings that you did ‘after the antique’, so to speak. This first painting in the exhibition [Virgo] dates back to 1985.

UP. These early works are in monochrome. I used ancient sculpture as a model, but then I moulded those sculptures into something quite different. If you look at these early paintings, hopefully you can see that I’ve tried to capture an essence which is missing from most contemporary art these days. It’s the classical sense of construction. Nothing is casual. I tended to leave the head out in these paintings, because the head gives the figure an expression, and I didn’t need that. I was only interested in the structure – the classical structure. I took the ancient techniques, which have basically been forgotten now

JH. Do you mean techniques of painting, or of sculpture? Your works seem to cross the boundary between the two – I mean, these are paintings, but they are also very sculptural, both in the sense that you use sculptures as models, but also because of the techniques of incision that you use in some of the works.

UP. Both sculpture and painting, actually. I once met the son of a famous painter of the Nineteenth Century, and he explained to me how to work with tempera and oils, and taught me about the oil’s tendency to ‘reject’ the tempera. It gives the painting an effect of being consumed, and worn out. It’s a bit like a phantom. What I did here was that I first prepared the board – the wooden board, covering it with gesso, just like the ancients did. Then I drew the figure on the board, starting to sketch out the gestures, to give this sense of movement.

JH. Why do think it is that these ancient techniques have been forgotten?

UP. Well, they were lost in the 1950s, after the Second World War. It’s partly because the Americans arrived, since they changed the art market.

JH. Is a painting like the Virgo based on a real statue, one that you’ve seen and then taken as a model?

UP. Yes. In this case I’d seen a particular statue, but then I reworked that model. I was initially attracted by the forms which swirled around, and I adapted these forms into the overall ‘phantom effect’ of the painting. I added some gold touches to the ‘marble’ surface. You can see the brush strokes, how evident they are. Sometimes I add details, like the hand in the next painting called Homoquidam (1986). Here I added the hand because it seemed so much in harmony with the forms of the drapery.

JH. …while the other hand is truncated, which brings the materiality of the sculpted body back into focus. And what about the names of the images? Virgo and Homoquidam are Latin…

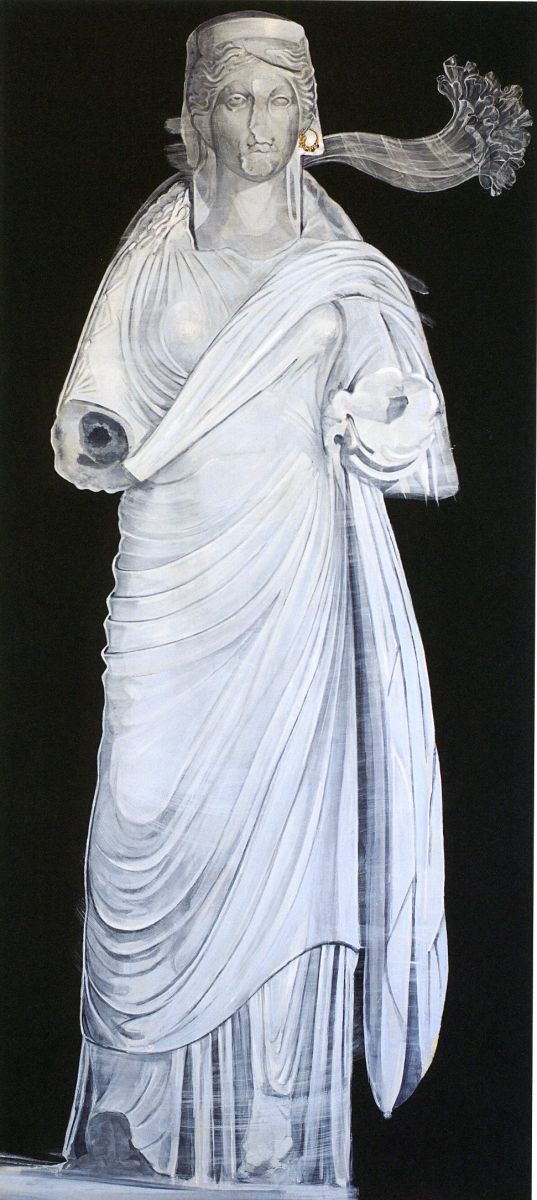

UP. …yes, and the next one is called Mater. At this time I’d rediscovered the idea of maternity, and of the Earth Mother, the Mother of Art, and it was also the ancient goddess. Another of the paintings here is based on a statue that was found in Syria. But I modified it and added a Greek earring, as well as some flowers which were intended as a symbol of regrowth.

L’orecchino d’oro, 2014. Oil on wood. 185 x 85 cm.

JH. Who had the idea of this exhibition in the Markets of Trajan?

UP. Well, several years ago I’d done a big exhibition inside Hadrian’s Villa. That was organised by someone in the Soprintendenza – it was the person in charge of Hadrian’s Villa, who had seen these works, and who wanted to arrange a big exhibition for me. That was in 2008. Then last year I had an exhibition in Scolacium, the city founded by Ulysses, in Calabria. That one lasted for six months. And then this year, the Director of Trajan’s Markets suggested that I put this exhibition on here.

JH. Were some of the paintings made especially for this space? And is there a particular dialogue with the ancient sculptures on display here?

Sibilla, 2013. Oil on wood, 185 x 85 cm.

UP. The idea was for the exhibition to take the form of a procession. So the paintings lead you through the space, on into the next room, and then the next. And as you move through the exhibition, the paintings start to get bigger. This is a Sybil, that I took as a model, but again played around with the composition. I used the velificans motif to ‘close’ the composition, so to speak. It’s a trick that Caravaggio often uses, and it functions to give a sense of movement, balance and harmony to the figure – a sense of connection. Again, I left the head off, to leave space for the imagination.

This was around the time that I started using colour. I wanted to evoke the colour of bronze, so I mixed gold dust in with the paint. This is one that changes with the light. With a stronger light it really explodes. Many of my other paintings from this period are highly coloured. This particular blue colour gestures towards infinity (indicates the Demeter).

Demetra II, 2003. Acrylic on wood. 140 x 100 cm.

JH. In his introduction to the catalogue, the exhibition curator Gabriele Simongini makes a comparison between your work and that of Yves Klein. And I definitely see that here, with that really strong blue. It reminds me of his blue Victory of Samothrace. Do you like Klein’s work?

UP. Yes I do. He’s someone else who retains that classical form, while adding something modern, making it contemporary again. I have a strong link with the French art scene because I studied and worked in Paris, and exhibited for many years in France. In 2003 I was invited to the Salon d’Automne for the centenary year. I sent three paintings, which I figured they’d put them in a corner, but they ended up doing the Press Conference with Chirac in front of this one! Perhaps it was because it had the French colours in it, but they loved it. And again it’s got that strange effect with the tempera.

JH. Do you have a favourite ancient building, or object?

UP. Well, it would have to be Hadrian’s Villa! But then there’s also Phidias, and the metopes of the Parthenon. If you look at how the ancients structured space, you can’t change or improve anything, because it’s perfect work. Caravaggio is the same thing – you can’t even improve the angle of an elbow. It’s all perfect.

Mercedes Italia, 2004.

JH. I wanted to ask you about your relationship with the fashion world, which would seem to be quite a natural one given your interest in fabric and drapery. Simongini makes this point in the catalogue – that the assemblage of your paintings evokes a fashion show. And I also noticed that this exhibition is sponsored by the Fondazione Micol Fontana, which is a very important name in Italian fashion history.

UP. Yes, fashion designers have often shown an interest in my work. Karl Lagerfield bought one of my paintings, a red figure that I’d shown in Paris quite near to his studio. And another designer actually did a fashion show in front of my paintings! That was Egon von Furstenberg, in 2004, for Mercedes Italia. He installed seven large works by me, and the models paraded past them in long colourful dresses.

Presenze, 2015. Acrylic on canvas. 190 x 290 cm.

This next piece I’m showing you is one that I did in my balcony on Filicudi off the coast of Sicily, where I go for three weeks every summer. This group composition was much more challenging than my usual single figures, because I had to deal with the question of how to organise the space. Some of these figures I invented myself, but look at the boy – he’s based on a figure by an Italian medieval sculptor called Tino di Camaino, who was a true genius. The woman laying down is based on a figure by Arnolfo di Cambio, a great sculptor of the Trecento, who did Piazza Venezia. She’s called Sete [Thirst]. And her pendant figure is inspired by Stefano Maderna, by his Saint Cecilia, the patron saint of Music.

JH. Would you describe this as an allegorical painting?

UP. It’s more a general ‘triumph’ or ‘retrieval’ of Classicism. Right now, we’re in an awkward moment. Humanity is fragmented. The ancients, they created philosophy, painting, sculpture, music, architecture…and everything was connected. It’s not like that today.

I worked really hard on this painting. There’s an amazing light by the sea on Filicudi. I drew directly on the canvas. I don’t mean to compare myself with Caravaggio, but it’s that same technique that he used. He also drew directly onto the canvas, starting off with large brushes to outline the structure of the composition.

JH. Are there many other contemporary artists in Italy who draw creatively on the classical past, or do you feel quite isolated in that respect?

UP. There aren’t many. Italian art lost its direction – its connection with the Classics – around the time of the Arte Povera movement in the fifties. Artists then started to forget the importance of antiquity, and even to disparage it. There is a handful of people working with ancient material today. One I can think of uses old photographs and then retouches them, adding things. But that’s slightly different. When you paint something completely new, then that energy remains in the canvas. I just love doing these things. For me, this is happiness.

Find out more…

- For more images from the exhibition, see the catalogue Umberto Passeretti: Un Presente Antichissimo, edited by Gabriele Simongini.

- A large selection of the artist’s work can be found on his website umbertopasseretti.it

- This short film about the exhibition features Umberto Passeretti, Lucrezia Ungaro (Mercati di Traiano, Museo dei Fori Imperiali) and Gabriele Simongini (Exhibition Curator)

.JPG)