Practitioners' Voices in Classical Reception Studies

ISSN 1756-5049

You are here

- Home

- Past Issues

- Issue 8 (2017)

- Howard Hardiman

Howard Hardiman

Portrait image by Julian Winslow.

Howard Hardiman is a research-led artist based on the Isle of Wight (UK) who works in a range of media including digital art, pen and pencil drawings. He has also written and illustrated graphic novels including Badger (2008) and The Lengths (2013). His 2015 exhibition Mythology, hosted at Brading Roman Villa on the Isle of Wight, was a series of twelve digitally-created images emerging from his engagement with classical myths.

This interview with Emma Bridges was recorded via Skype from Howard’s studio on the Isle of Wight on 10th October 2016. It is one of a series which was recorded for Practitioners’ Voices in Classical Reception Studies as a result of the colloquium ‘Remaking ancient Greek and Roman myths in the twenty-first century’ which was held at the Open University’s London centre on 7th July 2016.

EB. Thank you for joining me in conversation today, Howard. You recently held an exhibition of your work entitled Mythology, which is a series of twelve images drawing on some of the stories told by the ancient Greeks and Romans. What was it that first led you to think about classical mythology?

HH. I’m probably similar to a lot of people in that I watched Clash of the Titans as a child, and that sparked my interest! But in relation to this exhibition the sequence of events is that I did a comic book a few years ago called The Lengths, in which I gave everyone dog heads, because it was important to keep the characters quite anonymous. That then got me thinking about the idea of people wearing animal faces. I think people might read a book where they see a dog and empathise with it more than if they saw a person. It made me ask myself what it is about these people with animal traits that seems to be so continuously compelling for us. That got me reading a fair amount of folklore, which then led me towards classical mythology as that’s what we have the most information about, and it’s bonkers. I’d done more comic books, and I’d been spending all day every day drawing, to try and keep up with the kind of timescale where I had to make a page a day. I was wondering what would happen if rather than doing a page a day I actually spent a month on one picture. That’s what drew me to these ideas of quite monumental portraits of figures from classical mythology.

EB. So what sorts of things stimulate your own impulse to create these new works – is it, for example, artefacts or texts from the ancient world, or are there artworks which others have created in response to the stories which have inspired your own work?

HH. It’s a mix of several things. For some images it’s quite specific, like the griffin drawing is very much based around Adrienne Mayor’s research on protoceratops. The griffin that I drew was half mythological griffin and half palaeontological one. Then with other pictures a lot of the time it was about being able to read primary source texts in translation and spot the points in stories where things don’t add up. I wanted to get away from the filter that we usually have for classical mythology which is the opinions of white Victorian imperialistic men. If we take out all of that agenda, what cool things do we spot? It was things like the story of Orpheus where at the end of his life he’s torn to death by the women of Thrace. I don’t think I know of any other story where humans kill a demigod, and someone who’s even more than a demigod because his mother’s not human either. We’ve kind of overlooked the fact that the only demigod-killers we’ve got are these women. That led to all sorts of research about the role of women fighters and so on. For me it isn’t so much that I want to illustrate the stories as they were told, or necessarily throw that completely out of the window and come up with something completely different now. It’s more to do with finding little overlooked details and trying to get people to stop and look and think. So we know the story about the Minotaur, for instance. I was struck by the fact that he was killed by his brother, and they were both sons of the same storm god. It made me think that it would be horrible to be a demigod. How on earth do you go around with this incredible torrential storm or whatever as part of your nature? It must be so difficult to contain it. With the Minotaur I then thought of the labyrinth as being more of a mandala than a prison or a maze. You’ve got the hero and the monster, but the monster’s the one who seems to have overcome its godly or bestial nature, and is in this labyrinth which is meditative, and [the monster] wears its sins on its face. He’s then killed by his bloodthirsty and brutal half-brother. It made me think that maybe it’s the Minotaur who’s the hero here, but maybe those described as heroes were pretty awful. The heroes in classical mythology can be mass murderers and rapists but they’re still seen as glorious heroes.

Asterion, the Minotaur (2014). Giclée Print, 60cm x 81cm.

EB. There are so many really dark elements to myth, aren’t there? Sometimes there can be a tendency to put the stories on a pedestal without acknowledging those problematic elements. I’m interested in what you suggest about the fact that you’re operating in relation to this wider tradition, but at the same time pushing against it in some ways.

HH. One of the things for me, as one of the ‘lucky’ working class people to have gone to a grammar school, is the sense of classical references being used as a way of denoting power. People talking about empire, for example, might allude to Rome as if it is the ideal – and then you remember that [Rome] was brutal, and they were fascists, and it was terrible. I like going, ‘Yes, you’re right, this is a really cool story, and I’m fascinated by it…but, by the way, did you know…’ Say, for instance, the stories of the Arktoi sounded like they were stories about places where girls, and sometimes boys, went, but all of the stories say that everyone who went returned as women. It’s this transgender narrative. If you can speak that language and go in and see that the classical world was really multifaith, multicultural, spread over a much greater realm of influence than some try to pretend, maybe that can get people to think again about their imperialistic fantasies. But the stories are really iconic.

EB. They’re stories which have been retold and reinvented for millennia from so many different perspectives, and yet they never seem to lose their appeal for audiences and for artists. What do you think it is that makes ancient myths so engaging as themes?

HH. I think you can look at any kind of mythology and you’ll always find these dominant narratives that seem to have something in common with one another. Some versions imagine it as being quite crystalline but these were sort of Bronze Age gods of a really dark and bloody point in human development. If these have their origins in Ice Age folklore, there’s something incredibly appealing to me about that, that they’ve been told and retold to different audiences in different ways ever since. You can use the changes in the stories as a way of mapping movement of people, but also of beliefs and values. I suppose it’s the case with any folklore like that – if you go back far enough it speaks to these universal themes of desire, jealousy, fear of the elements, or even things like needing to understand the seasons. That was one of the things with Brading Roman Villa, where on the island [the Isle of Wight] there’s no evidence of any kind of forceful occupation by Rome here, and everything seems to be quite peaceful; but on the mosaic on the floor there you’ve got something that looks very much like the Wheel of the Year. Is this them going, ‘We know you’ve got your pagan traditions which talk about the year, but we’ve got similar things’? And there’s all that stuff about how Romans couldn’t quite figure out who Hecate translated to so they ended up making her this three-faced goddess. And that’s not how we understand religion to work; but it sounds more like it’s a system of shared values and beliefs.

EB. So for your exhibition at Brading Roman Villa, were the pieces there commissioned specifically for that setting, or did the exhibition bring together works which you had already created?

HH. It wasn’t context-specific. When I was applying for Arts Council funding for the exhibition I came to a realisation of the depth of knowledge that the volunteers there have, as compared with the amount of information that visitors go away with. There’s also very little crossover between the audiences for art galleries and museums, which surprised me. So when I talked to the Arts Council about it they were very keen to support it because it was bringing gallery-style art into a museum context as a way of then understanding more about the building that it was being shown in. The issue of audience caused some unexpected issues along the way in that people who would normally go to a museum were expecting me to have pages of text telling them references for everything, rather than me just showing the works. People expected there to be a lot more text where, as artists, we prefer to go the other way and have as much doubt and ambiguity as possible.

EB. Do you think, then, that having the works displayed in that setting might therefore have changed viewers’ responses to your work as compared with them being shown in an art gallery?

HH. I think so. When you’re a contemporary artist trying to deal with classical mythology there’s always the risk that people are going to try to put you into some kind of ‘fantasy art’ category. For me, the way that I work is so tied up with engaging with academic thinking about the stories that I’m telling. Having the work displayed in a museum does change the way people approach it. There’s the sense that while you’re looking at something that’s an imagined image from an imagined version of an imagined story, that’s got ancestry. That’s perhaps not so much the way you’d look at things in art galleries. A lot of my fascination with classical mythology came from when I used to be a sign language interpreter for talks at the National Gallery. That got me into Titian. It’s funny now looking at his work again when I go to a gallery having read a lot more. I’m looking at it going, ‘I think I know which books he’s read’ and saying, ‘I don’t know who that’s meant to be.’ It’s changed the way I relate to his pictures, whereas before I think it was much more about the drama, the overly melodramatic gestures, the movement and the feel of it. Now there’s a bit of me that’s asking where the story comes from, and what it’s doing. I don’t think that’s how we normally approach artwork.

EB. Did you think that your work might also shed new light on the artefacts which are on display at the villa? For example, Brading has some really important Roman mosaics.

HH. Yes. The museum staff said it was really useful that it encouraged people to be a bit more open in their interpretation of the artworks in the villa. Generally I think we go to a museum and expect to be told what things are; having an art exhibition there meant that people could then look at things and realise that we don’t always know for sure what [the mosaics] are pictures of. They’ve got a mosaic of the story of the fox and the sour grapes; it’s one of the very rare pictures of a building in a mosaic and it has a wine-press in the background, so we might ask why they’ve chosen to include so many images about using grapes for drinking. For me it’s also about trying to make it all come alive a bit more.

EB. There’s something about authority when we’re looking at an artefact in a museum, isn’t there? You read the tag and it tells you a date, and what the object shows and so on; but even if that’s a considered interpretation based on evidence it’s still one person’s interpretation, yet it’s sometimes presented as the last word, with no room for discussion. In fact there are often several different ways of looking at something.

HH. Yes. It’s an area where artists and academics can work together quite well, in that, as an artist you’ve got a lot more licence to deal in ambiguity. You can overreach, you can overstep, whereas academics often have to be a lot more cautious and certain about things they put forward; there needs to be proof. With a lot of these things we’ll never actually know whether the stuff we look at as mythology would be an equivalent to [modern] politics, or pop. Anyone looking at our culture in a hundred years could think that we worshipped Hello Kitty. It makes me wonder sometimes whether we take it too seriously, too literally. There seems to me to be a clear distinction in people’s minds that in the classical period mythological stuff was metaphorical; that was fine and you didn’t take any truth from it. It didn’t have to be real to have truth. I think that’s a difficult thing for academics who deal with truth, with fact, rather than necessarily some kind of poetic truth. Lots of television shows say things had ‘ritual significance’ – what does that mean?!

EB. You said that you found that visitors tended to want more explanation about your work. In your exhibition catalogue you have descriptions of the mythical backstories relating to each image. Was that something which was originally planned as part of the exhibition?

HH. There’s always been a narrative element to it. I think that because they’re such familiar stories but I’m telling them in unfamiliar ways it’s only fair to give people a way in, particularly if I’m dealing with obscure aspects or putting a completely different spin on things. Like the story of Medusa – I think that if she was a priest to Athena, then she was a priest to long term plans and science. I don’t think she would have suddenly turned into this angry, rabid monster, having survived rape and been given a weapon that kills any man who looks at her. I think she’d turn round and say, ‘Okay, goddess, you’ve got a plan, haven’t you?’ Everything that happens subsequently is in favour of the goddess. It does need a little bit of unpacking for people when they expect to see the Ray Harryhausen kind of serpent monster and instead I show them a scientist.

Medusa (2015). Giclée print 59cm x 84cm.

EB. Do you feel that if someone doesn’t know the story it changes how they feel about the image, and their interpretation of it?

HH. I think it does. For instance, the picture that I did around the idea of the Arktoi, where you’ve got this image of a caring mother bear kissing a young child on the head. For me it sounded amazing to think that at this really vulnerable point in life, when you’re going through puberty you get to go away to the forest, dance around, learn about bear shamanism, learn the facts of life and then come back to be an adult. But when people see the image they don’t necessarily see the story or the reasoning behind it; they just see the tenderness. A lot of people read the child as being a boy; for me, it’s a child and the gender doesn’t matter. Then other people would find different readings and different connections with it. One of the people who bought it said that it reminded her of her relationship with her father as he was really protective and looked after her, and that gave her strength. That’s exactly what this picture is about; the historical reference point shouldn’t prevent people from being able to find their own stories, because that’s the point of stories! I do think it’s something that I’m always going to encounter – the degree to which I want to have ownership or authority over how people read the things I’m presenting to them. I’m not entirely sure where I want that to end up.

EB. Well, in creating the text too you’re creating a new version based on what you’ve taken from the things that you’ve read and looked at. It’s another layer of reception, in a way, as well as the image.

HH. I’m really keen to try and do some longer versions of the stories in text too at some point. There’s a sense at the moment that we don’t really have many sacred spaces; and I think that art galleries are good for that because they’re places where you can go and it’s quiet, and you can look at things and not understand them, and that’s the point. In life we don’t embrace doubt very much. I think that galleries are maybe the nearest thing we have to temples nowadays. So if I’m presenting work that’s referencing old temples it would be really nice to do some kind of performance-based storytelling inside a space with these images of gods. It also makes me think that I’d really like to write the stories out a lot longer, but I don’t want to go into the well-worn territory of Robert Graves and the like.

EB. Was it quite a challenge to produce those very condensed versions for the catalogue?

HH. It helped that when I did my undergraduate degree my main discipline was poetry, so I was thinking about how to get as much information into as few words as possible, but still to leave it so that people can go off at different tangents. It’s really tricky to try to get a fragment that is representative of what ended up as being a solid year or more of research. I’m also really mindful of the fact that I’m dealing with stuff that people have dedicated their entire lives to learning about, and I can never know as much as they do about this, so I need to make sure that I’m respectful about that, but also about the fact that these are gods, and you’ve got to be respectful. That said, I really like the earlier versions of Medea, where she’s really terrifying; the ‘Stars, hide your fires’ that Shakespeare used, when Medea says [of the princess in Euripides’ Medea], ‘Let her pain burn brighter than the wedding torches.’ That’s not a woman who’s troubled by what she’s doing, and yet we always see versions of her where she laments the decision to kill her kids. I don’t think she’d have stopped for a heartbeat! You realise that there are so many different paths you could possibly go down with each of these stories. It’s a case of how long you hold those versions in your head before one of them becomes the one that you go with. For example, in the story of the golden fleece, drawings of the fleece show it still with the horns on it. That made me think, they flayed this animal who could have brought people back from the dead – these heroes are awful!

EB. You tend in this exhibition to focus in very closely on individual characters or objects – for example, in the case of ‘Golden’, it’s the head of the ram that bore the golden fleece that you’ve chosen to show. You’re condensing an entire story into a single figure, or at most two, in one image. I’m intrigued by the choices visual artists make in working out which bit of a story they select to depict. In some ways that seems to me to be much more challenging than writing a longer narrative of a whole story. How do you decide which parts of the myth you’ll focus on?

HH. For me, I start by making notes and sketches for about fifteen different versions. Quite often in the end it’s about aesthetics more than the message you want to show. Sometimes it’s about the thing you like drawing. But it’s really tricky, for example, to condense the story into the look in someone’s eye. I think that’s why I do still produce these little fragments of text with them, because there’s so much more for each of these stories that you could go into. There’s part of me that just loves the idea of telling the stories, and the images are not illustrations but glimpses of moments of the story. I’m not always entirely sure how I end up settling on one thing or another.

EB. Could you also tell me about your technique, and the process of actually creating the images?

HH. Most of my drawings are done digitally, so I use a graphics tablet and a stylus. I like that, as it’s using a tablet and a stylus to tell stories that were originally written down with a stylus on a tablet! I use a bit of software called Manga Studio which, as the name suggests, is used for drawing comics. It seems to do a pen and ink mark a lot better than anything else that I’ve tried. I end up with paper sketches, with reference photographs and hidden layers of different images that I can look at to make sure I get things right. One thing about drawing digitally is that you can do a lot of things, you can change your mind about things a lot more; the flip side though is that you can get caught up in the most tiny tiny detail on it. As a result the drawings that I’ve done for the exhibition take a very long time to finish, because there isn’t an obvious settling point – you can go back and redraw the entire thing. The most maddening one was the eye on the griffin, where I spent about a week drawing every single bit of the eye cell by cell. It’s one of these things where it doesn’t reproduce well in the catalogue but when you see the original work people look at it and look again, getting closer and closer. It’s insane. I quite like using digital media to create something that looks like it might be copperplate engraved. If you think of digital art people have a particular type of image in mind. I quite like the idea of using digital media to make something physical. It’s also talking about mythology, and about gods – there’s something resonant about the fact that I’m doing it all using vector drawing, so each mark is a mathematical formula, it’s a graph. You can only ever understand this thing through an intermediary. To me that sounds like a way that we can understand religion. We’re dealing with these bizarre baffling things that we can never understand directly, and that we can only really understand through how they manifest in our 3D world. If someone showed you all the numbers and graphs and things for the file, it’s meaningless. To me that feels quite poetic – there’s something quite appropriate about there not being an original.

EB. It’s another way of challenging people’s preconceptions about what something is, isn’t it? You’re suggesting that people have certain ideas about what digital art looks like and what it does. That’s also how we might think of classical myth, in a way.

HH. I think for me it’s quite useful to stay as contemporary as possible with process, because you’re talking to people now. Although I am thinking of doing a lot more with painting, using the language of these Renaissance artefacts. I work in a range of different media, but the unifying thing is drawing rather than anything else.

EB. I’d also like to know a little more about some of the themes of the work. You mentioned earlier your use of human and animal characters; you also look at some of the hybrid forms we find in myth, like Minotaur or the figure of the satyr. You suggested that some of the beasts take on human characteristics. That comes across particularly strongly for me when I look at your work, particularly in the eyes, which you’ve also mentioned. What led to that interest in thinking about how you might characterise the animals?

HH. One of the things that struck me when I approached these stories as an adult was the way that classical Greek understanding of mythology was a lot more animistic than we tend to read it as being. So you’ve got a goddess of thought who’s called Thought. Is that actually about believing in a person that is separate? It made me think that it’s a lot more shamanic, in a way, with rituals where you have to dress up as an animal for something or another. I just think there’s something about using animals as imagery that bypasses an awful lot of our cultural programming. If you show a person, immediately you are making assumptions based on their haircut, on what they’re wearing, their ethnicity, their perceived gender, these sorts of things. With animals a bull’s a bull. It bypasses a lot of that conscious interruption. I think for me it was the story of the Minotaur and the idea of wearing your godhood visibly in that way that got me thinking a lot more about classical myth as being from the Bronze Age, and having these connections back to people gathered round the fire, rather than necessarily people in the city. I think with that inevitably animal imagery comes through a lot more. Aside from the classical myths I find a lot of European folklore generally really fascinating – figures like the horned man, for instance. There are so many ways we might think about this, different ways that it might manifest itself, but we all seem to understand what it might mean when you wear antlers. There seems to be a shared understanding that it somehow makes you the king of the woods. Similarly we’d know what it meant if someone wore a lion skin or something like that. It gets you past the language part of your brain a little bit quicker, and gets you straight into feeling things.

EB. In your work, some of the figures that we might think of as monsters, like the Minotaur, or Medusa, become victims, and become very human, and very humane. Are you keen to overturn our ideas about what we think is going on in those stories?

HH. As much as the versions that we’ve got have been filtered by Victorian men with their particular agenda, there’s also the sense that if these are based on actual historical accounts of battles, they’re the versions that were told by the people who weren’t slaughtered. That means that they’re written by people who slaughter, and there will be an incredible bias about how the story is told. In particular the thing that strikes me is the way that women get written out of having any agency. For instance, the story of Medea that we find in Pompeii is of this very troubled wife, whereas the Medea on vase paintings is flying through the sky in a chariot pulled by dragons, having killed everyone. It makes me think that something’s been lost here, and it makes me want to focus on the smaller stories, the things that aren’t shouted about. What fascinates me is the idea that the people we remember as heroes are awful; I like looking at the things they destroyed and thinking about what’s beautiful about those things.

In particular the story of Perseus and Medusa is interesting to me – he has to be spoonfed all the way along by these women who tell him where to go and what to do. Yet ultimately it all works in favour of the goddess, because the mission is to kill her enemy’s champion. This doesn’t sound like he’s a hero; it sounds like he’s a naïve boy who gets pushed into the right place. Given that she’s the goddess of long term planning, I think she knew what was coming! Yet we tend to say that he was given this wise advice, when really it’s just ‘Here is a sword; here is a shield,’ and she’s probably just waiting round the corner going, ‘Fine. Cut my head off; I know that this is coming!’ Either the heroes sound like they were nasty vicious brutal people, or they were utterly inept. Like Jason – he’s really clueless, it’s Medea who does everything. No wonder then when he decides to marry someone else so that he can be king, she reacts like she does.

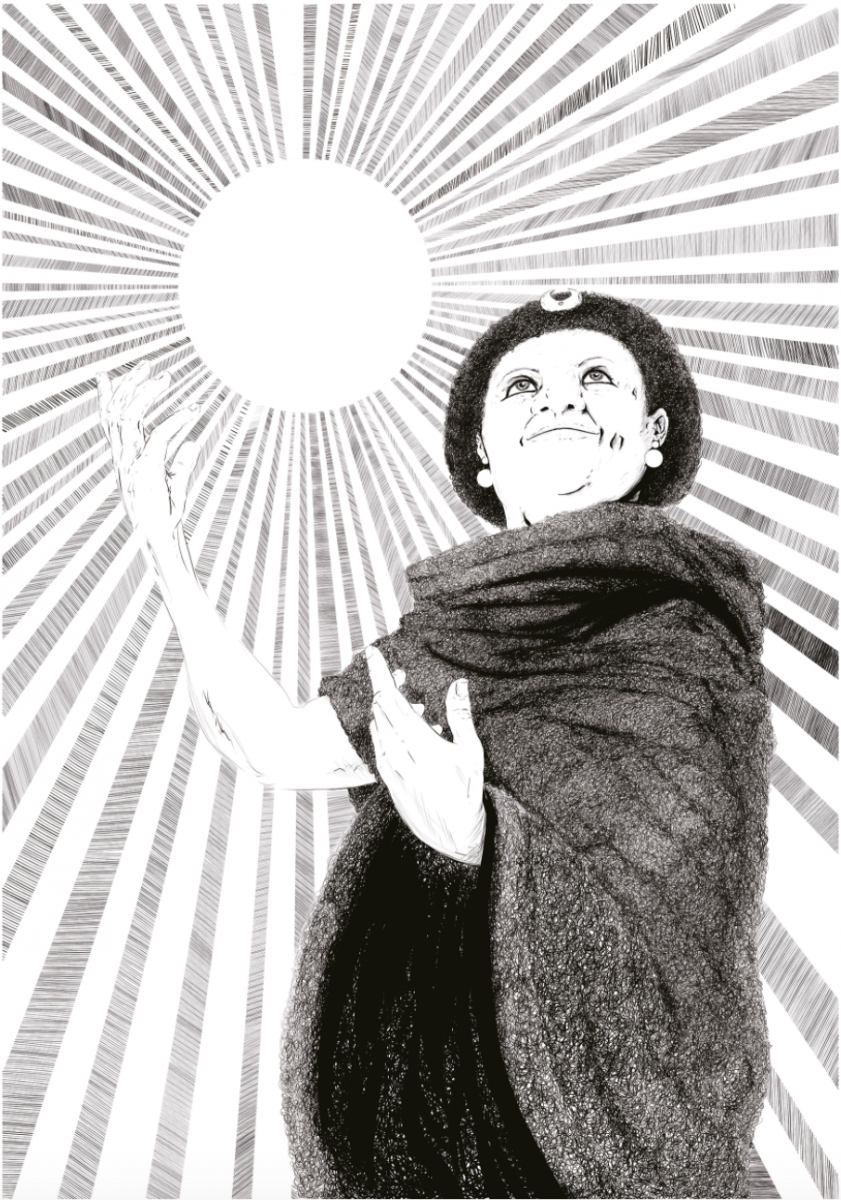

A lot of what I do is trying to look for narratives that have been overlooked, and are still being overlooked now. Just like queer history is very much suppressed, the history of women having any power at all is something that people find really difficult to acknowledge. I think if I can point these things out a little bit more, maybe the people who are so chest-thumping about how great Roman imperialism was might stop and think about the part women had in this thing they think was amazing, and maybe then think they won’t be so awful to women. It’s a hope, anyway! I think Hecate’s a good example as well, because the version we usually get is of this haggard witch that we’ve had since Shakespeare. But she was an African goddess with a really specific role in that she bore light through dark places, which is pretty cool. Also one of the texts says even Zeus worshipped her because she was so powerful, because she was the sole daughter of the sun. But hang on, we only hear about her being this hideous witch! Or there’s the part in the story of the abduction of Persephone where, when Demeter finally goes to Hecate, she pulls the sun out of the sky to ask him questions. That’s a level of power that we don’t really find in any of the other stories, but somehow that’s been erased because it’s the power of a woman.

Hecate (2015). Giclée print 59cm x 84cm.

EB. So you feel it’s important to give voices to characters who’ve been marginalised by the narratives as they’ve been created over centuries?

HH. Yes. For example, lots of stories talk about how amazing Hercules was. It does sound to me like he’s African. When you look at vase depictions of him he has the same kind of characteristics as those they gave to drawings of African people – the curly beard and so on. Then you ask who actually used olivewood clubs, and you realise that the Masai people did. People around that area also wore lion skins. Yet it’s strange that what we see is that he must be white; he becomes a ginger man, and a straight man at that.

EB. Do you think that in some ways your own experiences shape how you view your characters? For example I know that you’ve talked quite openly about producing art as a means by which you are able to cope with chronic pain.

HH. The way that I do my drawings is so repetitive and it takes a long time, so it becomes quite meditative for me. It’s meditation through action. Most meditation tells you to bring your awareness to your body; if I do that it feels like my leg is on fire so I don’t want to do that. Being able to focus on other things makes it a little bit easier to deal with. I think also the experience of having to rediscover how to live over the last few years with chronic pain has made me have more empathy, particularly when there are stories about horrible suffering being inflicted on, say, a really nice lion. It makes me think that I feel for the [Nemean] lion in the story. The lion is the first of these images that I did; the lion and the Minotaur were about a year before the other ones. With the lion it was very much this thing of having felt like I was invulnerable. I thought that although people in my family had had these chronic pain problems it was never going to get me. It’s like the hubris of the lion, thinking nothing could hurt me; and then the awful way that he gets killed. I do like the one version where it’s done by Hercules forcing his arm down his throat and then losing a finger. It’s so Freudian. For me it’s about learning to survive in a different way. Similarly with the Minotaur it’s the idea of someone who’s had to learn to centre themselves even though they’ve got this nature which could be so destructive and powerful and mighty, but instead they have chosen to be quiet and survive without hurting people. That resonated for me.

EB. I’m really intrigued by your Minotaur. I’ve recently been reading Steven Sherrill’s novel The Minotaur Takes a Cigarette Break and I feel that your Minotaur, who looks incredibly unhappy and misunderstood, really shares some of the characteristics of Sherrill’s Minotaur.

HH. Yes, it’s that thing of the Minotaur having been ground down. That’s certainly something that stuck with me from that book.

EB. It comes back to your point about characters who’ve been given a bad press, but who might have another side to their story, doesn’t it?

HH. Yes, I think the image of the Minotaur is also so caught up with quite a toxic version of masculinity. It’s all muscle and rage, but that’s really not good for anyone. It’s where we are as people now – we shouldn’t be having conquests with violence, but where would that then leave a Bronze Age god who is able to slaughter? How would they then adapt? It’s about how we might adjust to having a more peaceful version of mythology, a more understanding or aware version that isn’t just about the heroism of people killing people, but instead looking at things like how incredibly clever people were then compared to now. Look at the Antikythera Mechanism, for instance. There was that thing where they got Swiss watchmakers to make it and they learned things about clockwork from it. And that at a time when the lifespan was a lot less than it is now. It makes you wonder what we could be capable of if we were able to focus like that. There’s also the flipside that they could do that because of having enslaved other people, though. That’s often overlooked when we talk about classical stories.

EB. Yes, it’s important that we don’t gloss over the parts that might make us feel uncomfortable about the ancient world.

HH. I think it’s also about understanding how their belief system informs their way of life. People don’t tend to talk about the Labours of Hercules about him having been enslaved in order to atone for the wrongs that he’s done. Finding the story of Omphale made me think about that very differently, not just, ‘He killed his family so he had to do what the man in a pot said.’ There’s so much licence to do what you like with the story because we don’t actually have a source text. The fact that people were outraged because he was being sold to a Turkish woman was fascinating to me. You’ve also got this idea of Hercules as an older man who can never stop having these violent rages. He’s killed his family and in order to understand and atone for it he becomes a wife. Then Omphale goes off and does her own thing for a few years, then she hands godhood back to him, saying, ‘You’re forgiven now; you understand this.’ To me that idea of redemption through understanding is fascinating. Imagine a legal system built on that rather than punishment or imprisonment; the idea of understanding the thing that you’ve done, the harm that you’ve caused. Live through the life that you took – I find that amazing, even though all of the versions of the story that we seem to have are comedies. There’s this really beautiful poetry to it for me.

Omphale (2015). Giclée print 59cm x 84cm.

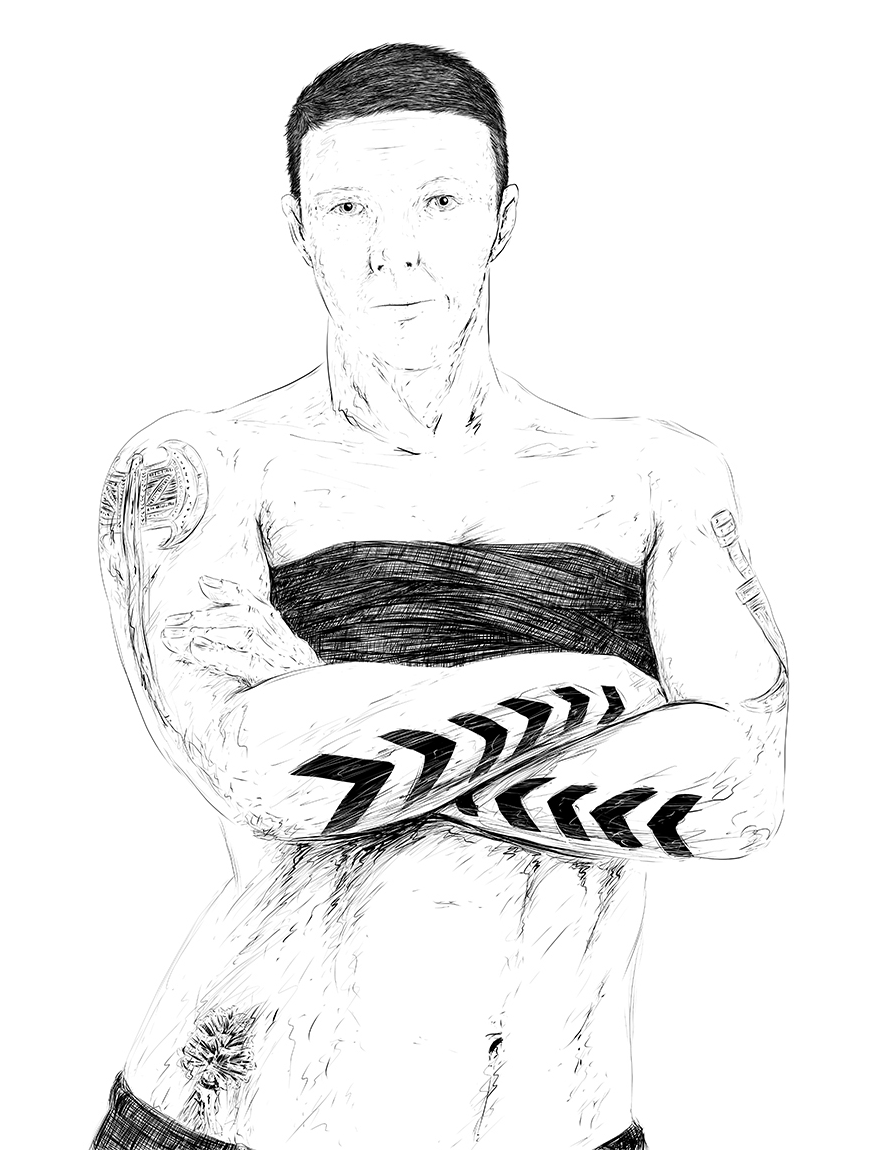

Thracian (2015). Giclée print 59cm x 84cm.

EB. You’ve talked me through the thought processes behind several of the images you created. Is there one which stands out for you as your favourite?

HH. I’m really proud of the one of the Thracian woman. I worked with a female model who is six feet tall and a boxer, and she was with me when I was working on the image one day during an open studio session. A number of times men would come along, look over my shoulder and ask, ‘Why’s that man binding his chest?’ She was standing there right in front of them, and the look of ‘Oh, for God’s sake!’ that she kept giving them – I thought that was what they needed! I have a lot fondness for that.

EB. I also wanted to ask about my own favourite, which is the owl of Athena. Why did you choose to focus on the owl, rather than the goddess herself?

HH. I like the idea that, instead of having a lightbulb that goes on in your head, you’re suddenly caught by this tiny little owl. The sense of ideas as silent hunters felt so beautiful to me, as an artist. I also liked the slight absurdity that she’s the goddess who guides you through military conflict and yet one of her attributes is this adorable tiny owl. It’s the duality of it, that she presides over slaughter yet has this cute owl. It makes her a lot more rounded as a character. It’s also the fear of the blank page as an artist as well. It took a lot of deliberating before I felt I could leave the rest of the image blank apart from the owl. It needs to be like that, that the owl’s seen something that we can’t, and that it’s swooping in to strike.

EB. So what’s next for you? What are you working on at the moment?

HH. I’m currently artist in residence at Art Space Portsmouth, and what I’m doing there is a narrative computer game based on the absurd government rule that if you can move more than twenty metres you’re not disabled enough to require any support. So I’m going to be going along with a measuring rule and stopping every twenty metres and then writing or drawing something about that place. Woven into that are going to be lots of narratives about freedom of movement. So it’s storytelling but not classical mythology. The other thing that I’m working on is that in 2017 I have an exhibition with another artist called Marius von Brasch. The whole exhibition is about mythology and change. A lot of his work is about medieval alchemy. His work is very abstract; mine’s very concrete. We’re both intrigued about how when we look at similar subject matter it can end up so different. From his point of view my images are very certain. They’re still quite ambiguous but I think my work’s very much anchored in a physical experience, whereas his is a lot softer, a lot vaguer. So I’ll be coming back to some classical mythology for that. One of the things I’ve realised over the last couple of years is that the work that I do is probably better based around projects where I can work with academics rather than necessarily making work to sell to people for their houses. What I’m really hoping to do is research projects where I can actually feel that I don’t have to make it pretty, but where I can have a deeper understanding of it myself. I think it’s fruitful in both directions then.

EB. I’m really glad to have been able to talk to you, and I think it’s a conversation that we should continue in future too. Thank you very much.

HH. Yes – I think that artwork can be a way to introduce people to these stories who might otherwise not have access to them. Good to talk to you.

Find out more...

You can see more of Howard Hardiman's work on his artist website: http://howardhardiman.com