Practitioners' Voices in Classical Reception Studies

ISSN 1756-5049

You are here

- Home

- Interview with David Raeburn

Interview with David Raeburn

David Raeburn has had a long and distinguished career as a teacher in schools and universities and as a translator and director of Greek plays. He is also the author of books on tragedy and joint author of a commentary on Aeschylus’ Agamemnon. He has worked extensively with school and university students at summer schools. In this interview he looks back on his career and comments on his current work and future plans.

This interview with Lorna Hardwick was recorded in Oxford on Monday 16thJuly, 2018.

- A PDF file of this interview is available for download.

- David Raeburn's CV can also be downloaded.

Lorna Hardwick: This is Lorna Hardwick, Monday 16th July 2018, in discussion with David Raeburn on the subject of directing and translating Greek plays. David, thank you very much indeed for agreeing to do this interview for Practitioners’ Voices. It’s a pleasure and an honour to be able to talk to you about your work. I wonder if we could start by asking you a little bit about how you first came to be engaged with Classics? What drew you to the subject and then subsequently to Greek drama?

David Raeburn: I started learning Latin at eight and Greek at ten, and when I went on to Charterhouse – where the classical education still very much flourished – I came to enjoy Greek literature particularly. And I’d always, right from my childhood, had a tremendous interest in acting and in drama. So I suppose it was a natural consequence that when I was an undergraduate reading Classics at Oxford I did my first production of a Greek tragedy, in 1947. And that led to the productions I did later on, particularly my employment at Bradfield College, where the tradition of performing Greek plays in the original goes back to the nineteenth century.

LH. When you spoke about being interested in acting yourself, was that while you were still at school and did that involve ancient material? Or was it Shakespeare or modern material?

DR. No ancient plays at all, really. I remember when I was at my preparatory school, and I was sick, my Greek teacher brought me up a Loeb edition of Euripides, and I suppose that was the first contact I ever had with a Greek play – it was Alcestis. I didn’t make much sense of it at the time, but I was impressed that the ancient Greeks wrote plays. I may have made a mental note then that I would rather like to pursue these plays later on. The first ones that I read in Greek at Charterhouse were, I think, Cyclops and then Prometheus Bound.

LH. As you developed your interest in Greek plays and in directing and translating over your career, how did you find that that related to your other scholarly interests, as a teacher and as somebody who was engaged in doing commentary work on the texts?

Audio Extract 1

DR. I think I have seen my work on producing Greek plays as largely an extension of my work as a teacher. Of course, my main hobby was directing plays, and I did a lot of other plays like Shakespeare and so on when I was a schoolmaster, but I think an important motivation was to work with students who were doing Greek, and to bring these marvellous works alive by actually performing them. In later years I came to co-author a commentary on the Agamemnon with Oliver Thomas, which we called ‘A Commentary for Students’, published by the Oxford University Press, and I think that it probably contains a great deal more about the way in which a Greek tragedy works as a play than most commentaries on Greek plays do.

LH. Yes I am sure that’s right. I have benefited from using it myself and have recommended it to a lot of other people for that very reason. Tell me, when you were an early career teacher, very keen on spending time with plays and productions, did you find you got support from your colleagues and from your Head, or did you have to do that entirely in your leisure time?

DR. Two I did were at Bradfield where it was a big tradition, and I got a great deal of support within the school for that, though I always felt that with some of my colleagues they were a bit uncomfortable about the famous tradition that the school had inherited. I had to give place, for example, to cricket during Greek Play week, and organise understudies so that the cricketers could carry on in their cricket matches as a priority, but by and large Bradfield was very supportive. Then when I was Headmaster at Whitgift School I decided I wanted to put on a Greek play in Greek. It was the only one I did there and I got a lot of help from colleagues. In fact, most of the Greek play performance work I did when I was a schoolmaster was at the Joint Association of Classical Teachers Summer School. I came into my own on that because there were very nice open-air theatres at Dean Close School in Cheltenham and subsequently, after I ceased to direct the Summer School, at Bryanston. In these theatres I felt very much at home,organising rehearsed readings, which I eventually managed to turn into proper performances without scripts, when I chose plays that were short enough for the very hardworking students to learn by heart.

LH. That sounds as though it was a terrific achievement from them as well as from you.

DR. It certainly was.

LH. Yes. Tell me about the very first Greek play that you directed – particular challenges, particular things you learnt along the way that have helped you subsequently?

Aeschylus Agamemnon, Bradfield College Greek Theatre, 1958. The king enters his palace over crimson tapestries.

DR. I think I’d only actually seen one production of a Greek play before I embarked on the Agamemnon which I put on in 1947 at Christ Church for the Oxford University Experimental Theatre Club. That was in Louis MacNeice's [1] translation which I still think is one of the very best translations of Greek tragedy ever written. The play I had seen done professionally was Oedipus Rex, directed by the great Michel St Denis [2], whose thoughts on direction I very much admired as I got to know about them later on. But just seeing that production with Laurence Olivier as Oedipus… I suppose that showed me the way, to some extent. I still had to think through how I was going to manage the Chorus in an open air setting, particularly because the Chorus in a sense was the lead character in the Agamemnon. I worked out my own solution, and that turned out, I felt, to be reasonably successful, so I rather stuck to that particular style of showing the Chorus in big, formal, symmetrical groupings, with stately processional movement rather than a lot of running around in more elaborate dancing.

LH. That is very interesting, because it sounds as though your particular production of MacNeice’s translation was a lot more successful than the critical disaster that the staging of his play in London provoked.

Aeschylus Agamemnon, Bradfield College Greek Theatre, 1958. Clytemnestra standing over corpses of Agamemnon and Cassandra on eccyclema. Chorus formally grouped in attitudes of horror.

DR. I believe that was a rather odd, quirky production, though it had music by Britten. I did the play very straightforwardly. We hired rather awful costumes! Clytemnestra and Agamemnon were vaguely Roman and the Chorus looked more like Chinese mandarins than Greek elders, but never mind! It was a start, it was the best that we could do in those days, shortly after the war. And the music was really very simple. I didn’t have the Chorus singing. I used a drum to create certain effects and I had some horns and trumpets to provide a little incidental music at certain well-chosen moments.

LH. We have talked very much about Greek rather than Roman drama, and tragedy rather than comedy. Has your focus always been on Greek tragedy or have there been forays into other areas as well?

DR. Not really. Greek tragedy really has been my primary love. I did direct a rehearsed reading once of Seneca’s Phaedra. I liked Seneca for its Latin and declamatory potential, and I liked what he did with the Greek lyric metres; but he didn’t seem to me to have anything like the human truth that is to be felt in the Greek tragedies. As far as comedy was concerned, I was never very much into Plautus. I had a great friend who revived the Latin play at Westminster, Theo Zinn, and he used to do them very well with his students, so I rather left that with him. I always felt that Aristophanes was very difficult to bring alive because so many of the jokes are contemporary and nobody is going to get them. Of course there are certain aspects of his humour which are universal, but one ought to be laughing all the time in an Aristophanes play. As it happens, I am just thinking about writing an adaptation of an Aristophanes.

LH. Well we shall await that with interest. I take absolutely what you say about the difficulty of getting across the jokes. I remember just a few years back seeing a production of a translation of Aristophanes in which the jokes had been updated, you know, to the present day, and things politically were moving so quickly at that time, the jokes had to be updated daily!

DR. Yes, absolutely.

LH. You spoke about your very first production in 1947. I wanted to ask you how over subsequent years and subsequent plays your approach to directing, and indeed to translating, has developed and how much the two activities have influenced each other.

DR. Well, I suppose my approach to directing Greek tragedy has been fairly constant. I have really wanted essentially to make the play’s words and the action clear – to make them interesting, emotional. I wanted to be faithful to the text in the sense that I’ve never wanted to impose a modern concept on the text, to appropriate it. My aim has been to interpret the text, to commune, as it were, with the poets and to ask myself what they were trying to say in their own historical context. I felt that the play’s universality would then speak for itself, if one told the story directly and clearly. And here I’m at odds with the normal modern approach to directing these Greek plays. Though they are often exciting, beautifully acted and hold the audience’s attention, I don’t think I want to go and see them because I just find them rather irritating. They seem so often to miss the poet’s point. If, for example, one sees the Bacchae as essentially concerned with gender issues, with the male and the female, then I think one is just concentrating on peripheral aspects of what Euripides is thinking about in his own time and missing out on what is genuinely relevant.

LH. One of the things I find quite interesting about modern rewritings or versions of tragedy is when there is an opportunity to compare different productions of the same text. I am thinking particularly of Seamus Heaney’s The Burial at Thebes, which was based on Sophocles’ Antigone. Its initial production in Dublin, which was very much translocated in terms of culture and so on, along the lines you have been suggesting, was not actually very successful, whereas the subsequent production which was, if you like, much more culturally neutral, and had very simple set and costume, was actually much more direct and audiences actually engaged with that much better than they had in a production that had tried to bring the play to them. And that relates quite interestingly to what you have just seen saying.

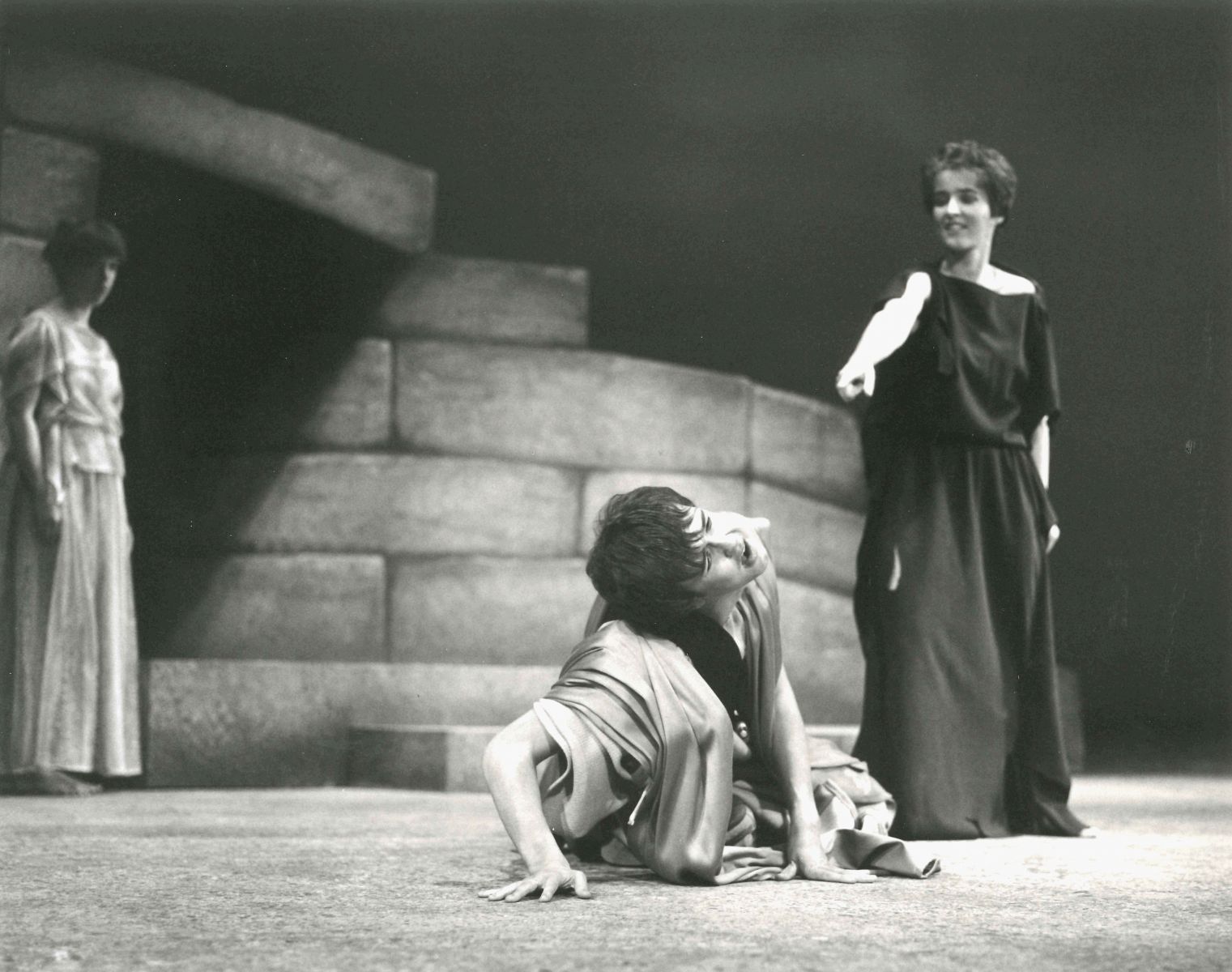

Euripides Electra, Arts Theatre, Cambridge, 1980. Electra goads Orestes into matricide. Greek costumes with representational set for presentation in indoor theatre.

DR. Seamus Heaney does adapt a considerable amount. And then one would say, ‘Okay, that is a new play, with a different title, by a different poet, and best accepted on its own terms’. If I see Sophocles’ Antigone advertised, I get rather cross if I find that the production is essentially focused on things which don’t seem to be the primary preoccupations of Sophocles.

LH. Which is one reason I think why the changes of title are quite interesting and indicative, and honest, in that sense.

I wanted to ask you – you’ve had experience of directing in the original language and in translation. What are the different challenges that that presents to you as a director?

DR. Performances in the original of course take much longer to rehearse, they require high standards of diction, and they may involve teaching people who don’t do Greek or understand Greek to say it as poetry. If they are clever actors, with a lot of presence, they can be remarkably convincing. In the end, though, I find that scenario bogus, because I feel that fundamentally an actor has got actually to be thinking the words. It has got to be in the mind, and it is that that makes the thing convincing to an audience. With my first Greek play at Bradfield, Oedipus at Colonus, the Oedipus, the Creon, the Theseus were all boys who didn’t know Greek and it was extraordinary what they achieved. This could be justified in educational terms as it presented them with an enormous personal challenge which they managed to surmount. But I don’t think that is to be recommended, except in rather esoteric circumstances, because the effort involved is really disproportionate to the results finally achieved.

LH. Does that mean that for instance you might think that in the case of school students who don’t know Greek, that actually working with them in a play performed through a translation is dramatically and educationally satisfactory?

Audio Extract 2

DR. Given the pressures that schools are under and the sort of time that is available, I have come rather to the conclusion that performances in translation are beneficial for the actors and also more tolerable for the audience [laughs]. It’s a very strange business, this performing in the original. It’s rare, for instance, for a university department to put on a Schiller in German or even Racine in French. Even if the grand sonorities of Greek are well spoken and well delivered by actors who know Greek, it can still be very hard for them to get across. When I did Hecuba for the Oxford Greek Play in 1996, I did have Greek speakers, people who were able to deliver the Greek intelligently and forcefully, but there was something missing. One also needs actors with magnetic personalities that will really engage the audience’s attention. So perhaps that was more of an exercise for the people who took part in it.

LH. In the world there must be a very, very small constituency of actors who are both fine actors and who know Greek sufficiently well to be able to speak the lines.

DR. Absolutely. So although most of my actors in the recent run of productions that I have done with my New College students have been Classicists, I’ve chosen to do them in English because the demand on their time is far more reasonable, and I also think they have been more accessible to the audience.

LH. Now that we’ve got on to your work with the New College students, could we talk a little about the fascinating production that you did this summer with them [2018]: your choice of play, your choice of the actors, what you were hoping to achieve in the open-air setting?

Left: Sophocles Oedipus at Colonus, Bradfield College Greek Theatre, 1955. Oedipus' final moment before he leaves to die. Other principals, Chorus and extras grouped in formal symmetry. 'Greek vase' style set and costumes, in terracotta, black and white.

Right: Sophocles Oedipus at Colonus, Warden's Garden, New College, 2018. Oedipus with Theseus and Creon (some Chorus in background). Tragic conflict in modern dress.

DR. I did Oedipus at Colonus at Bradfield in 1955 and I was attracted by the idea of doing it again in translation. This time I did it in modern clothes. I had done two Sophocles plays fairly recently, Oedipus Tyrannus and Antigone, in ancient Greek costume. To do that well is very expensive because, although they look simple, they have got to be fitted properly and it needs professional dressmaking if they are to hang and hold up really well. Modern dress is more acceptable to an audience these days, so I thought I would do it in that. It tied in with the intimacy of a very simple garden setting with trees that delightfully suggested the Grove of the Eumenides which Oedipus approaches at the beginning of the play. The presentation worked. I also had a very good actor who’d worked with me on Ajax the year before and I knew would make an excellent Oedipus. Often the choice of play can be determined by the availability of certain actors who one knows will be marvellous in particular roles.

With the Chorus of Elders of Colonus I saw an opportunity to introduce some more girl students - I think that’s important too these days. So I made them a group of villagers rather than elders and I don’t think that was too much a violation of Sophocles. Still, even in this more intimate atmosphere, I kept the main choral odes formal, often with symmetrical groupings, because they are set numbers that derive from ritual performance. Here is the point that I have always felt to be absolutely crucial, the point that Michel St Denis insisted on: you find the truth of the play through the style. Fidelity to the style of the way in which Greek tragedies were composed, to the actual medium, means taking account of the formal alternation between episodes for solo actors and discrete choral movements. This is something fundamental which needs to be fully appreciated and exploited. In no sense do I think the Chorus should be seen as a problem. It is right there from the beginning and an opportunity for the director rather than a difficulty.

LH. In practical terms with that particular production, how much rehearsal time did you have?

DR. Five weeks, and I had five two-hour rehearsals each week, so it wasn’t a very long rehearsal period. That excludes work I like to do beforehand with the principals just working on their words. That is another bottom line: the speeches, the long speeches particularly, have got to be carefully shaped and controlled. Edith Evans said of William Poel’s [3] productions of Shakespeare, ‘He taught us the architecture of the speeches,’ and that was something that another of my great heroes, Harley Granville Barker [4], thought was absolutely basic to the way he directed his actors in his productions of Shakespeare.

LH. Now, this production was acted in your own translation.

DR. Yes.

LH. Can you say a little bit about the extent, if any, to which you fine-tuned your translation in the course of rehearsals?

DR. Extraordinarily little, actually. I know that that again is unfashionable [laughs]. Actors rather like to play with a text. But I wrote it on that desk over there. I did a first draft, then fine-tuned it in a second draft, and by-and-large I found that worked. I have never had an actor say to me, ‘David, this line is impossible, please re-write it.’

LH. Yes, that was what I was very interested in probing, actually, because sometimes actors have said to me, referring to a particular translation, ‘Oh, the translation is lovely but I cannot speak it,’ or ‘If I can speak it, I can’t move while I’m speaking it.’

DR. Spencer Klavan, who played Oedipus, was very nice about the translation; he told me he was happy with it and found it good to learn. Actually, I find the translation and the production are very different sorts of process. In translating, I just like to engage with the Greek and to produce verse that is rhythmical. For the dialogue, I use a line, usually with five main pulses, that seems to be the norm for modern tragedy translations, rather like the verse T. S. Eliot used in his plays. With the choruses, though, I diverge from modern practice and try to follow the rhythmic patterns inherent in the original choral metres as exactly as I can. Where the appeal of melody seems to be more dependent on time and culture, the emotional effect of rhythm is something more universal and I believe that the exciting meters of Greek tragedy can be approximated to in English. This is often not easy to do, particularly in irregular patterns of rhythm such as the so-called ‘slanting’ dochmiac, which Euripides likes to use to work up suspense just before a murder happens. This is really thrilling in Greek and worth the effort that it takes to reproduce in English, even if it means some dodgy work with monosyllables to capture the right stressing. That, I suppose, was the initial motive for my wanting to produce my own translations. And if you go for the choruses, you have got to do the rest.

LH. You have worked very extensively with young people, either school age students or undergraduate students. Do you think there are… plusses and minuses…?

Euripides Bacchae, Oxford, New College Cloisters, 2013. Dionysus with the Bacchanals. Use of modern costume with some stylisation.

DR. I think that the plusses are the enthusiasm, their intelligence, their willingness to work hard and get on with things. With Greek tragedies one doesn’t want a whole lot of Stanislavskian [5] angst and exploration of character in depth. These are texts that you can just start to act, and students are happy to do that, I find. If I work things out beforehand and have got the movement blocking reasonably clear in my mind, it saves time. I know a lot of undergraduate directors spend an awful lot of time trying different things out, but I’d rather try to eliminate the less promising solutions beforehand and give the actors the confidence of repetition and familiarity with what I feel will work.

LH. Have you ever had rebellion from your cast or do they not dare?

DR. No, never. Again, most of the actors, certainly in Oxford, have not really been the theatrical ones who are doing three or four productions a term and want to make stage careers. They are largely my own students who are excited by the idea of doing a Greek play and are committed to it on those terms. Of course there are weaknesses, they may not have got the techniques, they haven’t got the kind of vocal stamina to sustain a long run of performances, but that is not in question – they’ve only got to do it three or four times. Some of them have already got a very sound technique. Some of them sing and have learnt how to support their breath from their diaphragm, so they can produce their voices quite well. More often than not, I find myself having to teach them simple techniques, and to eliminate fidgety movement, either with their feet, or doing too much with their hands. It’s often a question of explaining that less is more.

LH. Yes. You touched briefly earlier on in the discussion, when we were talking about the Chorus, on movement, and I think certainly in recent performance scholarship there has been an increased interest in dance and movement.

DR. Yes.

LH. What do you think is possible and what is desirable in terms of the kind of performance that you are working with?

Audio Extract 3

DR. Well I think, let me take ‘desirable’ first. There is rather an emphasis today on the theatre of the body as distinct from the theatre of the spoken word, but despite the fact that the Choruses were originally danced, whatever that meant, I think the spoken word is primary. The words of the choruses are really interesting and important in their meaning, and I don’t think that the fundamental philosophy that the Chorus often articulates is going to be clear with a whole lot of vigorous movement for its own sake. It depends a lot too on the character of the Chorus. Elders should not be expected to run around but move in a dignified processional way, whereas Furies will be rather more active in bodily movement. Movement also depends on what each choral movement is doing in the continuity of the play as a whole. That’s another thing that seems to me to be very fundamental. I don’t like generalisations about the Chorus at all. The function of the Chorus needs to be defined for each single choral movement. In the book that I produced, Greek Tragedy as Plays for Performance, that was something that I’ve tried to emphasise and tried to show – how each choral ode fits into the total shape of the play. So back to what movement is desirable: I think it depends so much on the context. As for practicability, some undergraduates can move beautifully, others are rather cumbersome and clearly this is something that is a constraint; but even under ideal conditions I would not want to see Greek tragedy as essentially a theatre of the body, which I suspect may be something that’s rather emphasised because television is so much a matter of what actors do with their faces, and in a very restrained way. You don’t get much theatre of the body on television and I think that live stage theatre has wanted to become more physical by way of difference– in Shakespeare as well as in Greek tragedy.

LH. I think that point you just made is an interesting one, which I have noticed particularly for instance in the live streaming that one now gets in local cinemas from performances from the National Theatre and RSC, that the directors of that have different strategies, in terms of how they use the zoom and the close-up and the emphasis on the face and how much they seem to just communicate what is happening in the theatre.

DR. That is of course a new kind of medium in itself, because it involves a selection from the live performance. That question of the photographed performance is very interesting. Another important point, to my mind, is the function of the Chorus during the episodes. Here again it has been rather fashionable for some directors to keep moving the Chorus around all the time. But that doesn’t seem to me part of the Greek tragic style. During the episodes, I see the primary job of the Chorus to be completely concentrating – to be assisting the audience’s concentration by their own concentration. There can be concerted reactions from time to time, of course, to mark particular points. But the constant shift-around, I think, is busy and distracting. Once again, this is a case where ‘less means more’.

Sophocles Antigone, Oxford, New College Cloisters, 2016. Antigone confronts Creon. Tragic conflict in ancient costume.

LH. Could I ask you now about what you have in mind for your next project?

DR. It is all rather uncertain at the moment. I may have sung my swansong! However, I am at the moment thinking about a double-bill of two short plays: Prometheus Bound, which I put on some years ago in a workshop production at Dean Close School with some modern dress elements, and also an adaptation of Aristophanes’ Acharnians to fit Brexit. It would be fun to have a farmer after Brexit who has lost his subsidies and is determined to make his own private treaty with Brussels. I have started to write a script and been trying to find modern equivalents and contemporary jokes. These days one needn’t be afraid of the bawdy humour and there is fun to be had there too. At some points one can follow the shape and logic of Aristophanes’ dialogue fairly closely, I’m finding, whereas one probably wants to write one’s own parabasis from scratch. In the scene with Euripides, where Dikaiopolis goes to Euripides to find a costume which will be sufficiently ragged as to inspire compassion, I think that the fundamental assumption could stand, but I am toying with the idea of turning Euripides into Shakespeare. He could come on in Elizabethan costume and talk about King Lear and Timon and Pericles rather than all the people who wear rags in Euripides’ plays.

LH. Wonderful. I think people will be looking forward to your next venture.

DR. Well I have got to persuade people that I ought to do it [laughter]

LH. Finally, David, can I invite you to speculate a bit. I mean a lot is talked now as frequently as in the past about ‘Classics at the crossroads’ and the next stage of development or retreat as the case may be. How do you see our field developing over the next ten years or so? How would you like it to develop, if you could be the great steerer?

DR. That is a terribly difficult question, I think. It is probably important to distinguish between classical scholarship and Classics as an educational discipline and also as a subject of general interest to the lay person. One has got those three different scenes.

As far as classical scholarship is concerned, I suspect that advances in technology rather favour a growing emphasis on archaeology, the decipherment of inscriptions and papyri and that sort of thing – rather away from the traditional mainstream of classical literature and of the classical languages which for a variety of reasons have lost some of their traditional rigour.

From the educational point of view, I still feel that the development of the mind and the enrichment of the spirit are, for me, the watchwords and the ultimate justification for Classics in the curriculum. Today the requirement of the public pressure for accessibility has to some extent watered those fundamental things down because I suppose they do presuppose a degree of verbal intelligence and perhaps some inclination or disposition towards a non-popular culture. But this is a really, really difficult problem and I’m not sure that those problems are going to be resolved.

LH. You mentioned just now the perceived public demand for accessibility, and I’m just wondering whether that doesn’t challenge us actually in a slightly different way. I mean, accessibility depends just as much on where you are starting from.

DR. Sure.

LH.…as on what it is you eventually want to access.

DR. Yes, yes.

LH. And it seems to me that recognition of the variety of starting points that people may have, not only at school age but subsequently in the wider community, can actually challenge us to respond in ways that are actually going to help people to come at some of the things you have been discussing today. In a way, we shouldn’t be defeatist, you know, accessibility is an opportunity as well as a challenge.

DR. That’s right. You, in your position in the Open University, have a special opportunity there, and there’s the particular constituency that you are trying to cater for and can cater for. I suppose that, because I have been a schoolmaster for most of my career, I am thinking about what a classical education – if one can still use that expression – can contribute towards the intellectual and human development of young people as they grow through their teens and through university before they go into careers which are may be entirely unrelated to Classics. And it’s in that area, which I’m naturally interested in, that I can see difficulties.

LH. Put bluntly, where do you think the classical scholars of ten years’ time, twenty years’ time, are going to come from? I mean, given the intellectual demands, the demands of the languages, the amount of time that is needed, the unpopularity with whatever political powers that be of things which are not directly related to STEM subjects or to getting large salaries and so on – where are our classical scholars going to come from? How can they be nurtured?

DR. I think it is a very, very difficult question and the most promising source is the top public schools [laughs] ….

LH. But aren’t they going to be equally sidetracked into the city or by the large salaries and influence, or politics, dare I say?

DR. Or the Bar, particularly. So many of the really clever people I have taught in college have become barristers and are now pursuing very lucrative careers. But no, the next generation of classical scholars…I’m a little bit disappointed about that. There’s already some evidence that the current generation of classical scholars is less well-grounded in Greek and Latin than people used to be. All right, there’s no need for them to be skilful in advanced prose and verse composition. On the other hand, one would like them to be able to code into the languages in some kind of simple way, really as a way of being sure that they can code out of the languages accurately and confidently. But I find it is a very difficult question, and am not by any means optimistic.

LH. I suppose one can only point to the fact that there are still experts in Sanskrit, in Akkadian, in Biblical Hebrew and so on – areas that have seemed to be very much threatened, and there will still be philologists in Greek and Latin…

DR.…I think there will continue to be a few, but not sufficient to go on to teach Greek and Latin on a large scale in schools or even in university departments.

LH. Okay. More optimistically, to take up as our very last point, something I think very important that you said just now about your third area of the importance of Classics – in the wider world, in the public domain. Again, looking towards the next ten or even twenty years, could you identify one or two aspects of ancient Greek and Roman thought and learning, that you feel could be particularly important for the wider community as we develop into goodness only knows what.

DR. I think so.

LH. What would you want to get over if you had the choice to say two things?

DR. Greek tragedy if it is honestly rather than self-indulgently directed, has got huge potential there, because drama has got an emotional, as well as an intellectual appeal. I think that is certainly worth saying. The Homeric epics also are universal in the appeal to the imagination, and there is the link with archaeology – which doesn’t interest me personally anything like as much as the marvellous stories and the way in which they are told.

Thucydides, I think, is wonderful, and it would be lovely to see if one could get Thucydides more widely known through the media, because his thinking – as it’s brought out in the speeches, and so on – is so interesting and so universal and again and again relevant to our situations. I also think Plato is right at the root of European philosophy and endlessly interesting. You may disagree with the answers Plato comes up with, but the questions that he asks are so fundamental, and he starts everything off. I very much like the idea that philosophy is an activity – something to be engaged in – in dialogue, to clarify minds. The assumption of total ignorance, that stance of intellectual aporia to start with is magnificent. Plato has a terrific lot to teach us. In Latin Cicero is so interesting as a historical figure, and his letters are really important. I adore Roman Augustan poetry but it is a mediation of Greek originals which need to be explored and understood in order to be able to engage fully with the work ofVirgil, Horace and Ovid, and there’s probably less promise of that.

LH. Well, David, thank you very much for having so eloquently given us a reading programme for the next twenty years, and for discussing your experiences as director and translator – we are enormously grateful to you for your time this morning. Thank you.

DR. It has been a pleasure.

Afternote: the Aristophanes project referred to by David Raeburn at the end of the interview was subsequently abandoned in favour of a production of Agamemnon, in the translation by MacNeice.

Notes:

[1] Louis MacNeice (1907 -1963), poet and playwright, came from Northern Ireland and was an associate of WH Auden, Stephen Spender and Cecil Day-Lewis. He was briefly a lecturer in Classics at Birmingham University and subsequently became a producer at the BBC. See further: Wrigley, A. and Harrison, SJ, eds., 2013,Louis MacNeice: The Classical Radio Plays,Oxford : Oxford Univrsity Press; Wrigley, A., 2015, Greece on Air: Engagement with Ancient Greece on BBC Radio 1920s and1960s,Oxford: Oxford University Press. [back to text]

[2] Michel Saint Denis (1897-1971), French actor, theatre director and drama theorist who influenced the development of European theatre, especially in respect of actor training in which he followed the emphasis of his uncle Jacques Copeau on text and interpretation. Founded the London Theatre Studio (1935) and worked with actors such as Alec Guinness, John Gielgud and Laurence Olivier. [back to text]

[3] William Poel (1852-1934), English actor and theatre manager, especially known for his productions of Shakespeare’s plays and his approach of using largely uncut texts with minimal scenery and pacy direction. Founded the Elizabethan Stage Society in 1895. Influenced Granville Barker. [back to text]

[4] Harley Granville Barker (1877-1946) was initially an actor who then became a theatre director and also wrote plays. An influential critic, his Prefaces to Shakespeare was published in five volumes over 1945-7. [back to text]

[5] Konstantin Stanislavski (1863-1938), Russian theatre practitioner, especially known for his system of actor training and rehearsal practices designed to enable actors to experience and become the characters they portrayed. [back to text]

Note on opportunities for learning ancient Greek and/or Latin:

David Raeburn referred to the importance of summer schools for students wishing to start or improve their classical language learning before or during their university courses. A number of classical organisations in the UK provide support and advice for students and teachers:

Classical Association: https://www.classicalassociation.org

The CA and the Joint Association of Classical Teachers have merged. The CA provides grants for classical summer schools with the possibility of bursaries for extra-mural courses in Latin and Greek. There are also bursaries for teachers.

Classics for All: https://classicsforall.org.uk/

Offers resources, grants and support for schools and regional networks.

Outreach Projects: https://ucl.ac.uk/classics/outreach/schools-colleges

University College London has a hub giving information and contacts for state schools and communities. The network targets socially excluded boroughs in inner London and schools with high numbers of disadvantaged children. Currently there are also three main projects: The Iris Magazine (for school students and teachers); the Inner London Ancient Drama project; the Inner London Latin Project (for state primary schools). Student teachers are supported in their work by King’s College London.

For Adult learners:

The City Lit is an Adult Education provider in central London and provides courses in classical languages. https:///www.citylit.ac.uk

The Open University currently offers undergraduate modules in Ancient Greek and Latin, which can be studied individually or as part of an undergraduate diploma or degree. The OU also offers a suite of free online resources for learning Greek and Latin. Find out more on this webpage (scroll down to ‘Online language resources’): https://fass.open.ac.uk/classical-studies/tasters