As we reach the end of the COP26 hiatus on Brexit the signs are not good. Reports from the talks on the Protocol are that progress isn’t occurring, even with the Commission’s striking opening offer.

This is all less than unexpected: the UK’s ask on ending the role of the CJEU in the Protocol never looking remotely viable and there has been no interest in using the Commission’s proposals to climb down from the flashpoint either.

COP26 might well have given a bit of breathing space, but only to something that looks heavily timetabled.

With that in mind, the moves on the EU side have mostly been about signalling intent to hit back hard should the UK follow through on Art.16. As Rahman has suggested, that might include both short- and long-term elements.

We’ve covered Art.16 itself enough for the issues to be relatively clear. As Howse points out in his new commentary on the provision, there’s rather more constraint than might first be apparent, but this also limits the direct response too.

As a result, it serves the EU to keep things broad-based, to make the matter less contained and to be less dependent upon the single provision.

There is plenty of flexibility about the implementation practice for both treaties, as the French had already identified in the Jersey impasse (also still not resolved, it should be noted), but the TCA also allows for some additional actions.

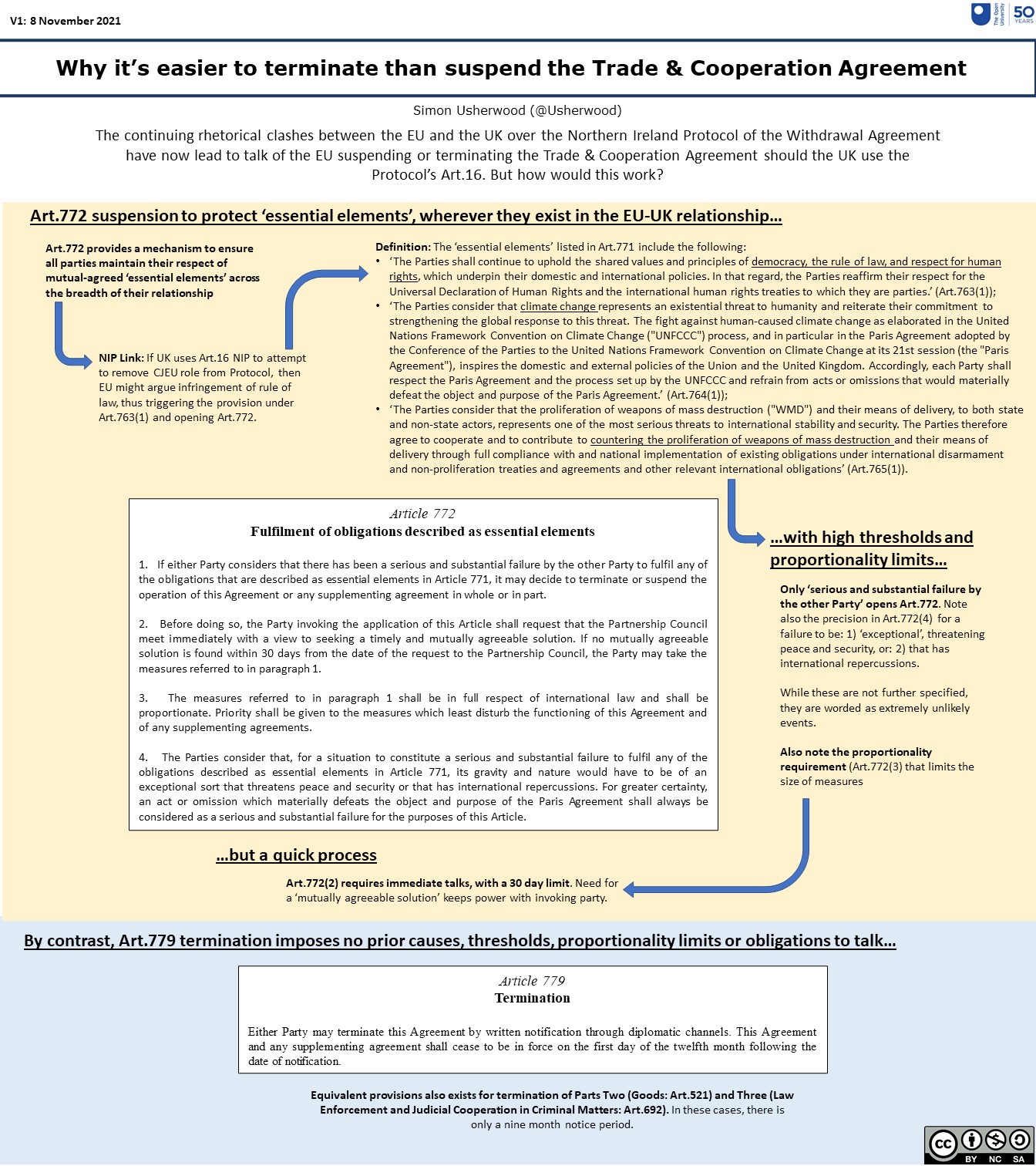

The graphic below sets out the suspension and general termination clauses for that treaty.

As you’ll see, suspension is more complex and requires a rather tough case to be made for justifying its use, based on a failure by the UK to apply rule of law. Art.772 doesn’t simply need some evidence of this – e.g. should the UK try to effectively remove the CJEU from the NIP – but also needs this to be a ‘serious and substantial failure’. That the CJEU hasn’t been used at all so far in the NIP’s operation becomes here a problem for the EU, as impairment of rule of law becomes that much harder to demonstrate.

Even if you can overcome these thresholds, there’s still a problem of proportionality requirements, which stop the EU from going wild with their response.

By contrast, Art.779 termination is a doddle: just put in your letter of notice and that’s that. There are even options to just terminate Goods or Judicial Cooperation, so there’s a bit more flexibility.

The process in this case would be entirely political, with the option to end the termination by joint consent.

I’ll admit to a degree of discomfort about all this. If the UK play chicken on this, then we end up with at least a partial non-application of the WA/TCA framework, which will make it harder to defend what remains. Trust will be even thinner on the ground than it has been, and the willingness to even start to consider new options will be vanishingly small.

Which makes the key question next week one of whether the UK really wants to go down this road. It will be one that offers minimal prospects of the EU moving off its lines on the Protocol, while definitely bringing a pile of economic and political pain. Yes, that pain will hit both sides, but much more on the UK.

Is the domestic political gain that might accrue really worth it?

Ironically, the continuing absence of a UK plan makes it seem more likely so: if you don’t have an end-point to defend, then you can wallow in the pain that much more easier.