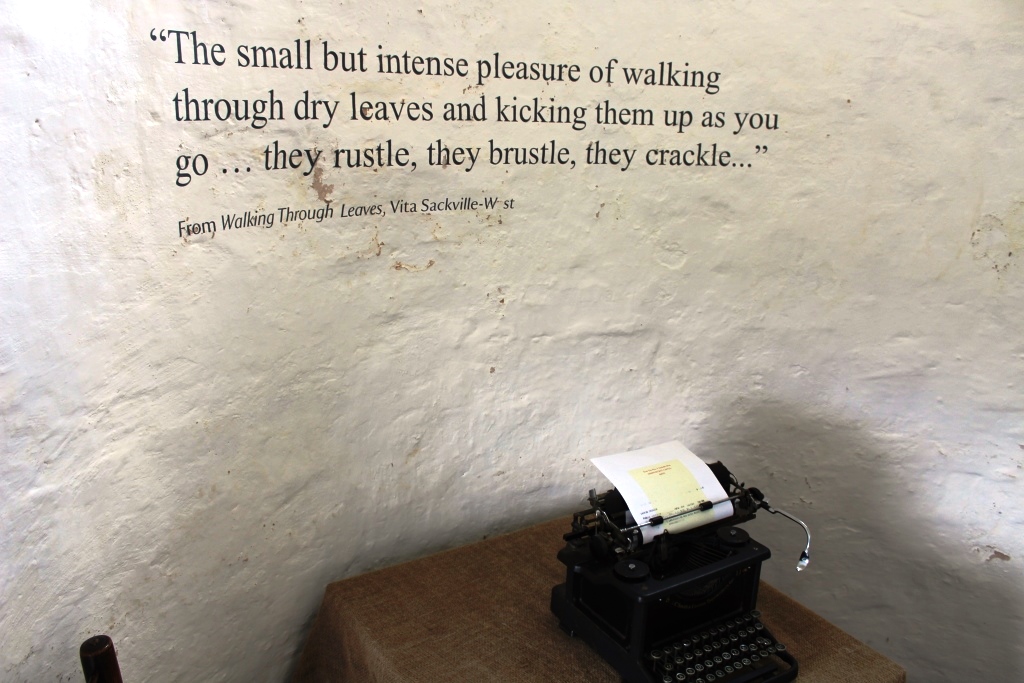

Over the past couple of months I have taken you on numerous trips to writers’ houses scattered all over the place : we have trekked across the moors to the Brontës’ home in Haworth, admired the desk at Walter Scott’s house in Abbottsford, and felt dizzy and bewildered while touring Hans Christian Andersen’s home in Odense. Recently, I have extended my thoughts from writer’s home, to writer’s landscape. I have been considering what putting a writer at the centre of a landscape, rather than a house, does to the landscape for the reader. The effect, I feel, is particularly interesting when the writer in question is a woman, as it reveals so much about how a woman-writer might think about writing, and be thought as a writer, in relation to the domestic. Continue reading

-

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

- Arthur Cosgrove on At a poet’s grave in a country churchyard

- Rick Robinson on Welcome

- Tyson S. Spero on Petrarch in Love

- Ian McMillan on Corelli-day

- Anny Entropy on Juliet’s House

Archives

- May 2021

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- February 2014

- January 2014

Categories

Meta