You are here

- Home

- blog_categories

- Inclusive Innovation and Development

- What can development learn from venture capital?

What can development learn from venture capital?

12 January 2018

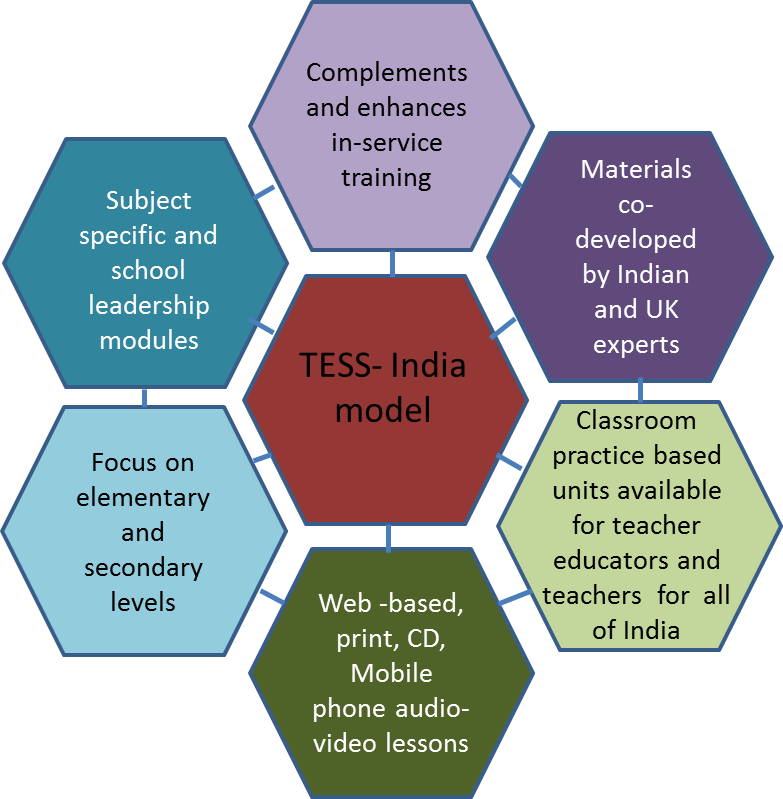

The goal of venture capitalists is to identify organisations with great ideas, invest in them – helping them to grow – before ‘spinning them off’ into the market and pocketing a healthy return on their investment. And, from the outset, this was the idea behind the aim of TESS-India, the OU’s open-access teacher support programme, to become self-financing. Established with seed funding from DFID in 2012 to establish proof of concept and market acceptance, by 2016 it had been ‘spun out’ – moving from a dependence on UKAID support to being an initiative independently funded by angel investor Save the Children, as well as by a variety of others from Indian State Government through to corporate social responsibility (CSR) finance. TESS-India’s financial independence and long-term sustainability in essence derives from sound product lines, delivered at an acceptable cost and in ways that consumers find convenient and easy to use.

Recently, as I trawled through the internet’s endless articles on ‘golden rules for venture capitalists’, it struck me how these could provide a useful framework to chart the TESS-India journey.

1. Make sure you are meeting a need: At TESS-India’s inception, the challenge of scale and complexity of India was daunting. The combined figure for untrained teachers and teacher vacancies at elementary level had reached two million. There were chronic subject shortages at junior secondary in science, maths and languages, while only 7 per cent of applicants had qualified in the national teacher eligibility test. The magnitude of the challenge called for something more than conventional college-based teacher education and cascade training: something both different and affordable.

2. Have a clear strategy and business plan: To avoid the issues around certification associated with pre-service, TESS-India addressed the teacher education challenge in-service. Tactics centred on collaborative work with Indian experts and policymakers to design and deliver open education resources (OER) which supported teachers in more learner-centred and engaging classroom pedagogy. Particular attention was paid to price point: the OU calculated that conventional in-service programmes cost around £38 per head per year, while for TESS-India the unit cost was just under £10 over the three project years. Indeed, the fact that many of the OU modules were provided free online meant many were incorporated into state-run pre-service education programmes. In essence the TESS-India materials infused pre-service provision by going viral.

3. Be careful to build relationships: A stream of different faces – often arriving from far away and with a slightly different take on things – can lead to confusion. TESS-India learnt over time the value of a single point of contact: available, local and approachable. Building trusting relationships that enable frank conversations – after which all parties can move on – is the bedrock of success. A big danger of net-based interventions is that they can draw you into a remote, top-down approach. However, do so at your peril. Long-term success is based on understanding the local political economy: not only what is possible, but how you need to work and who with to make it happen.

4. Know when it’s time to adjust or quit – and do it: Adaptive programmes are currently all the rage, but too often adaptation is seen as synonymous with technical innovation. In e-learning the attractions of the latest technology become seductive. What was truly ‘smart’ about TESS-India, however, was its attention to user needs and its consequent tailoring of what it offered. All resources, for example, were available in a variety of formats, including online, DVD, tablets, pen drive and Micro SD (in which materials were adapted for small screen use). Of course there was innovation – Raspberry Pi computers were used to create low-cost virtual nets – but critically TESS-India did not forget print for areas with little or no access to technology, or for those teachers more comfortable with older media.

5. Stay responsible and accountable: Investors expect a return. One of the things the OU had to overcome in the early days was a perception that TESS-India was ‘their’ project. However, once you accept investment you become accountable to your investors with a responsibility to keep the promises you’ve made. I’m pleased that TESS-India got a lot better at this – as evidenced by its impressive set of partners. Managing your stakeholders – who contribute in so many ways, from capital investment to intellectual content – is critically important, particularly for participatory endeavours.

Despite notable successes such as Mpesa mobile money, development initiatives that move from dependence on Official Development Assistance to self-sustaining enterprise are few and far between. With attention growing on the interconnected issues of sustainability and harnessing non-ODA financing for development, however, it is surely an area ripe for further exploration and TESS-India offers an interesting case study. The ingredients for its success appear to be common to those of business: clear end goals, smart strategy and defined investment horizon. To ensure you deliver these, do your research and your numbers, know your clients and build trust by responding to feedback.

Colin Bangay is former Senior Education Adviser, DFID India, and now British Council Director Education & Society for sub-Saharan Africa

This blog is also available in Hindi

Share this page:

Contact us

To find out more about our work, or to discuss a potential project, please contact:

International Development Research Office

Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences

The Open University

Walton Hall

Milton Keynes

MK7 6AA

United Kingdom

T: +44 (0)1908 858502

E: international-development-research@open.ac.uk

.jpg)