You are here

- Home

- Year of Mygration

- Day 181, Year of #Mygration: How the NHS has always relied on overseas labour

Day 181, Year of #Mygration: How the NHS has always relied on overseas labour

Potential NHS staff from outside of European Economic Area (EEA) will shortly find it easier to secure permission to work in the UK. Yet doctors and nurses from the EEA may no longer have the right to do so. Professor Parvati Raghuram looks at how the NHS has depended on foreign workers since its creation.

The claim that the National Health Service (NHS) would get an additional £350M per week if the UK quit the EU was arguably one of the most persuasive slogans of the Brexit campaign. The NHS has been one of the prides of the post-war social architecture and has come to be closely tied to British identity. Skilfully linking the NHS with Britishness was a winning strategy for Leave campaigners.

Commonwealth countries and the (Inter)National Health Service

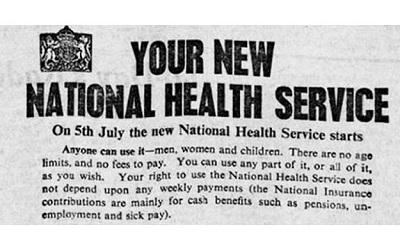

Migrant doctors from Europe, especially Jews who moved due to rising anti-Semitism in parts of Europe, had always formed a part of the medical profession in the UK. However, after the establishment of the NHS in 1948, many of the early flows were from the British Commonwealth countries. Training and work were inextricably intertwined through immigration regulations and the architecture of the health service, ensuring a steady supply of doctors.

The NHS has always been an international health service. It has been populated by large numbers of migrant doctors who not only served the NHS, but also constituted it, innovating and establishing it through specialist services in remote locations all over the UK. From the 1960s onwards, a number of legislative changes were made to attract migrant doctors, who would come to populate the lower and middle parts of the pyramidal medical hierarchy. They did not contribute to a pre-existing NHS; rather they made the health service what it is today.

The NHS and the EEA

Since the early 2000s, there has been a shift towards recruitment from within the European Economic Area. Freedom of movement within Europe led to an increase in the pool of migrant doctors, and in 2006 a dramatic shift took place - a virtual end to the migration of doctors who are third country nationals, i.e. those whose primary medical qualifications were obtained outside the EEA.

Migration regulations only tell half the story. Professional workers like doctors can practice in the UK after registering and obtaining the appropriate licence. Under EU law, doctors within the EEA cannot be discriminated against, but in June 2014 a new English language test was introduced for those trying to obtain the licence to practice in the UK. This led to a reduction in the numbers of doctors obtaining a licence, compared to those who registered.

Ten years later the tables turned as the UK voted to leave the EU. This led to large drops in the number of some health professionals such as nurses, although the full effects are yet to be documented across the sector. Growing staff shortages in some parts of the health sector are causing concern that the EEA will no longer serve the health workforce requirements of an ageing and rising population and its attendant demands for health care.

Although some areas such as emergency medicine, paediatrics and psychiatry have almost always been on the list of shortage specialties and are allowed to recruit internationally, shortages are now more widespread. Moreover, the cap on Tier 2 visas (previously the Work Permit category) from outside the EEA to a maximum of around 20,000 per year across all the professions - alongside the demand from some other sectors such as IT, for these visas meant that many areas of the health service remain understaffed. NHS bosses have claimed that this significantly affects their ability to deliver healthcare safely and have pressed for the removal of the cap. The Home Secretary has now capitulated to these demands. What is clear is that the NHS, as ever, struggles to remain national.

Yet this internationalism of the NHS is only one exemplar of the UK’s position within a world of connections - with Europe and with other countries, including the Commonwealth. Only when the power and necessity of these connections and their role in making the UK what it is today is recognised will anti-immigration arguments and sentiments about Europeans and non-Europeans alike be challenged.

Contact our news team

For all out of hours enquiries, please telephone +44 (0)7901 515891

Contact detailsNews & articles

Quarterly Review of Research

Read our Quarterly Review of Research to learn about our latest quality academic output.