Crime Statistics

The commissioner of the Metropolitan Police has always made an annual report to the Home Secretary in which he comments upon the state of crime in London. The documents accompanying this section provide a fairly typical image of the offences in late nineteenth and early twentieth century London. They show that most offences were petty such as drunkenness, common assault and larceny. Larcenies refer to petty thefts, differing from the more serious burglary (housebreaking) or robbery (theft with violence generally in a public place).

The Commissioner's report for 1905, for example, indicates that of the 94,693 cases recorded, 6,639 were simple larceny and 49,035 cases of drunkeness. London’s place as a major trade centre meant that theft of goods was a perennial problem; in the example shown tobacco companies were prepared to co-operate with the police. However, the majority of larcenies were on a much smaller level. The following warrant is illustrative of this: Caroline Curtis was sentenced to two months in the House of Correction for stealing two pairs of stockings from her employer. [A transcript is available.]

Fines had commonly been used to punish petty offences such as drunkenness. Yet as this document shows, the poorest of people still faced prison if they could not afford to pay their fine: in December 1919 Arthur Lucas spent a day in prison for being unable to pay a fine of 5 shillings.

You can see that there are two classes of crimes listed: indictable and non-indictable offences. The former relate to serious crimes which are dealt with by a judge and jury; the latter are less serious and dealt with in a summary fashion by a magistrate. The magistrates’ courts were also known as police courts. By the inter-war period there were 14 police courts staffed by 25 stipendiary (paid) magistrates. As a rule magistrates were concerned with maintaining the dignity and effectiveness of the law. A contemporary magistrate wrote that:

The justices' duty is to keep the peace and to maintain as high a standard as possible of honesty and decency within their jurisdiction. With this end in view, the chief consideration should be the general public good rather than the effect of the punishment upon the individual offender. […] The primary object of punishment should be the deterrence of other potential offenders who may be ready to follow an evil example (F. Mead, The Office of Magistrate (5th edn., 1922), p. 42).

By the twentieth century the police were concerned mainly with measuring the amount of crime by using indictable offences. Yet officers were aware that statistics did not reflect the actual level of crime. At the most simple level, there was a gap between reported crime and the number of people apprehended and charged for those crimes. The data for 1935 indicates that the majority of thefts involved relatively small sums of money. In 1848 all felonies against property cost £44,666. On the eve of the twentieth century, reported burglaries cost £88,406, i.e. 3 old pence per head of the population of the capital. While the vast majority of offenders were young working-class men, the small value of thefts indicate that the working classes were predominately on the receiving end of crime too.

All of these figures represent police responses to crime. As the module on the Policeman as a Worker shows, the police was a workforce of individual men who walk the streets; the discretion of these officers impacted heavily on the non-indictable crime figures. The police force as a whole is a bureaucracy; senior officers have always had to decide how to deploy their finite resources of time, men and money. Police statistics are often reactive in that they show what crimes officers chose to respond to. Obtaining sufficient evidence to prosecute an offence has always been a stumbling block. The bureaucratic dimension is important since the way that crime was recorded had an impact on the statistics. For example, in 1932 the Suspected Stolen Book was abolished. Prior to this reported crimes could be ignored in the official registers by placing them in the Suspected Stolen Book; sometimes it seems that they were even entered as Lost Property. This certainly made the figures look better but the point could also be made that while an individual might report a small item that had been lost as stolen, when they subsequently found that item they would not (or very rarely) go back to the police and report it 'found'. Using the Lost Property book might therefore also be seen as police discretion. From 1932 all crimes needed to be recorded in the station Crime Book so that accurate crime reports could be sent to Scotland Yard. Officers still needed reminding that correct procedures needed to be followed to create a 'true' picture of crime.

Where a charge was refused after an arrest, details needed to still be entered in the Refused Charge Book. Fortunately, some refused charge books have survived and are held at the MPHC. The following documents are from the refused charge book at St Mary Gray station in the 'R' (Greenwich), later the 'P' (Catford) Division. Samples have been given for refused charges for 1895, 1905, 1925 and 1935, the same year of the commissioner’s report samples. The numbers of refused charges at the station are small, not changing significantly over time from 10 in 1895 to 12 in 1935. Only five charges were refused in both 1905 and 1925. However, on closer inspection of the evidence, some changes are noticeable. For example, the majority of cases in 1895 are charges of theft, forming eight of the refused charges. Of those eight, the complainant declined to press charges in five of the cases. This warrants further attention. A number of reasons may explain why complainants declined to press charges. If the theft was comparatively trivial and the complainant knew the accused, or the latter was young, he may have decided not to take the time to attend court to present evidence. It is also possible that informal means of redress were used to recompense a complainant. We also need to consider that friends and relatives of the accused may have threatened the complainant. For four of the five cases in 1905 there wasn't any evidence to support the charge. By 1935 a broader spectrum of refused charges are present - from manslaughter to being accused of peddling goods without a license. The widening scope of refused charges may indicate the extended reach of the law in the twentieth century. These records also point to technological changes, as a few offences concern traffic incidents. In cases of drinking and driving – an offence not pursued with the same vigour as it is today – opinions differ between police officers and doctors over how to define 'drunkenness'.

Refused charge books are a useful source as they provide concrete evidence of the 'dark figure' of crime, i.e. the gap between recorded and actual offences. However they do not shed light as to why people refused to report crime. Other material held at the MPHC shows the difficulties encountered by the police in prosecuting certain crimes. These are most apparent as regards so-called victimless crimes such as street betting and prostitution.

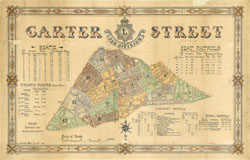

Betting caused innumerable headaches for the police. Many members of the public despised the class bias inherent in the laws, whereby it was permissible to gamble in certain clubs or at the racetrack, but criminal to do so in the streets. Off-course street betting was legalized in 1960. The following case is taken from Carter Street station in the 'L' Division. It demonstrates the difficulties that officers faced when trying to enforce the laws against street betting: a complaint was made against the senior officer involved in enforcing the law. The directives issued from the Executive Branch at Scotland Yard to the 'M' (Southwark) Division just before the outbreak of the First World War illustrate the safeguards that senior officers put into place to try and maximize the effectiveness of the law while minimizing the potential for corruption. These examples cover betting houses as well as street betting.

The police faced similar hazards in their fight against prostitution. It has never been illegal in England to sell sex for money, however certain aspects associated with the trade have been illegal. For example, until 1959 it was illegal to solicit on the streets and cause 'annoyance'. What annoyance actually meant was open to interpretation, hence the statistics can fluctuate quite markedly. The statistics show that the number of arrests plummeted from 6,214 in 1886 to 3,766 in 1887. This fall does not mean that the number of prostitutes fell in London. In July 1887 a 23 year-old woman, Elizabeth Cass, was arrested for soliciting. She denied the allegation. The press and parliament created such a furore over this case that the commissioner, Sir Charles Warren, issued an order that prostitutes should not be arrested for soliciting unless a third party was willing to supply corroborative evidence in court. Naturally many men did not wish to waste their time over such a trivial matter, or they were too embarrassed, and the number of arrests fell dramatically.

The problems associated with arresting prostitutes can be found in the 'M' Division Executive Orders book. London's place as a capital city, trading centre and tourist zone with a large transient population meant that prostitution was rife. Yet substantiating where prostitutes conducted their business could be hard to prove in court. For example, while brothels (a property with two or more prostitutes) were illegal, proving that a premises was used as a brothel was difficult. As a rule, the police kept observation on suspected brothels only when a local council had received complaints and were willing to investigate the matter. Examples of the type of evidence necessary to institute a prosecution against a brothel are to be found in the court information presented to Bow Street police court by St. Pancras council. [A transcript is available.] An example as to how the police responded to complaints about these premises can be found in papers from Hackney police station. [A transcript of the letter and report is available.]

Souvenir of the Tottenham outrage

Souvenir of the Tottenham outrage