Practitioners' Voices in Classical Reception Studies

ISSN 1756-5049

You are here

- Home

- Past Issues

- Issue 3 (2012)

- Norman McBeath and Robert Crawford

Norman McBeath and Robert Crawford

Norman McBeath is an independent photographer, based in Edinburgh, whose work can be seen in the National Portrait Galleries of England and Scotland. Robert Crawford is Professor of Modern Scottish Literature at the University of St Andrews and one of the country’s leading poets. Here they talk about their 2011 book Simonides, which features twenty-five black and white, duotone, photographs paired with texts translated from ancient Greek into Scots (and English). The book was published to coincide with an exhibition entitled Body Bags/Simonides which was shown at the Edinburgh College of Art as part of the Edinburgh Art Festival. Interview by Jessica Hughes (recorded in Corpus Christi College, Oxford, 6th February 2012). All images copyright of Norman McBeath.

- A PDF version of this interview is also available

- You can listen to Robert Crawford reading extracts from Simonides on the OU Podcasts website

JH. Thank you very much for agreeing to talk to me. Perhaps I can start by asking you both how the idea for Simonides came about?

NM. Well, it was Robert’s idea. We’d known each other for some time, so the idea of a collaboration wasn’t out of the blue. Robert was making one of his many appearances at the Edinburgh Book Festival, and he dropped a note in at my house (which is just around the corner from where leading writers are put up), saying that he had this idea that I might be interested in. I was out at the time, but then managed to get over to Charlotte Square and see him after his talk. We took two of those horrible plastic stacking chairs out onto the sunny lawn of Charlotte Square, and Robert told me about this two and a half thousand year old poet called Simonides, and the epitaphs and fragments he had written. And how he had translated them into Scots – not just because we were in Scotland, but for a very good reason – because he wanted to draw attention to this idea of a dying language. He read out this one poem he’d done and it had the word Ootlin in it, and this really stuck in my head. It means ‘outsider’, ‘stranger’. And he thought the whole idea would work well with photographs. So we agreed it was worth having a go!

JH. So the text already existed by the time you started working together?

RC. Some of them existed, and some of them were brought into being after Norman and I had sat down and looked at photos that he had – and then he took some other photos. So it was a genuine collaboration, in as much as we batted things backwards and forwards, and each of us brought some work into being to fill in the spaces. I’d been tinkering with these Simonidean fragments for an embarrassingly long time! I studied Latin and Greek at school, and I did Greek as a third subject in my first year of university at Glasgow. But it had rotted away over twenty-five years since then, and I just wanted to reconnect with that aspect of my interests. I’d never fallen out of love with Greek, but I hadn’t gone on reading it, and my Greek wasn’t good enough just to sit down and read, so I needed a crib. A few years earlier I’d gone to Yale to give a talk called ‘Why Literature Matters’, and for various reasons I’d chosen to speak about that fragment of Sappho on the evening star, which was a poem that I’d read when I was school. While I was there I’d gone into the university bookshop, which had this array of the entire Loeb Classical Library. And so I bought the five-volume Greek Lyric set, and brought that back and sat down with Simonides. Actually, I had thought about doing some more Sappho (I’d made one or two wee versions in English of Sappho), but I’m a huge admirer of Anne Carson’s If Not, Winter, and I thought that I needed to do something of my own. So I gravitated towards Simonides.

JH. Why did you choose to translate the fragments into Scots?

RC. I thought that Scots would give them – for most readers and hearers – a slightly alienating quality, but which would nonetheless be perceptive. And so the listener or the reader would have to reach a bit… but not reach as far as you would have to reach to get to ancient Greek. So they would both be foreign and familiar, which I think is something that is often imaginatively exciting. And they wouldn’t sound quite like the speech of generals, if they were in Scots. So although the Scots is to some degree synthetic, I wanted there to be a vernacular aspect to it. And the soundscape of Scots just seemed right for doing those poems.

JH. So did you approach Norman straight away?

RC. Not straight away. At the time I knew someone who ran a wee theatre company that did classical texts, and I thought that he could turn these into a show for kids. The poems were so short, and they were often bound up with memory, so I thought that kids could learn them, or could discuss some of them. Even though they are about subject matter that might be a little off-putting for young children, nonetheless I thought they might work in this context. But it didn’t quite work out, and so they’d been lying in a drawer for quite a while. When I showed some of them to Norman, I actually showed him two things I was working on. He didn’t like the other one at all but he liked the Simonides, and we thought ‘Ah, we can maybe make something out of these!’ So sometimes things don’t go in the direction you expect.

NM. And sometimes that can be a good thing!

RC. Yes indeed. Fairly early on we thought of one or two images that might go with the poems. And what interested me not least was that Norman (rightly, although I was initially surprised by this), although he had photographs that related to conflict zones, he didn’t want to use any of those. He wanted the relationship between the poems and the photos to be more oblique, and I think that’s part of what might be interesting about what we’ve ended up doing.

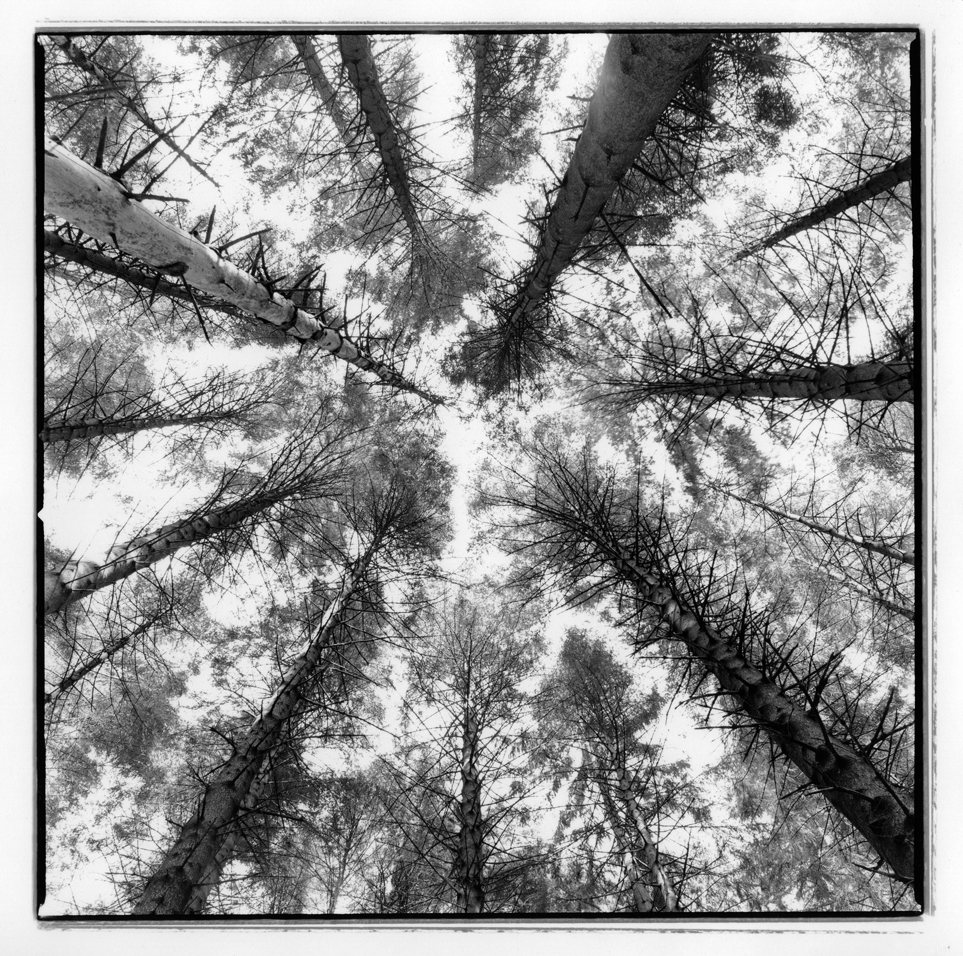

Orpheus © Norman McBeath

NM. I thought that was very important really – to have the link between the texts and the photographs to be as evocative as possible, and that thin strand of metaphorical connection to be as thin as possible, to give the viewer a chance to get their imagination going. That’s constrained if there is too narrow, too literal a harmony between the two. I felt very strongly that both the texts and the photographs should stand on their own as pieces, and be strong pieces like that, but be even stronger when they were together. And also offer more possibilities. They’re kind of bouncing back like a seesaw of different ideas.

RC. They resonate rather than illustrate one another.

NM. Resonate is the right word, very much.

RC. I think that sometimes one problem that emerges when you juxtapose photographs or paintings with poems – in an exhibition context anyway – is that people around are very struck with the visual material, but the poems take so long to read. And it’s embarrassing to have to stand for a while in a gallery!

NM. It takes more effort.

RC. You pass on to the next thing. Whereas Simonides’ texts are so short that one can take them in almost as one might an imagist poem. The fragmentary nature is actually a boon in this context.

JH. In some ways the poems look a bit like image captions - and actually, looking through the book reminded me of the experience of going to an exhibition, where you might look at a painting, then search in the museum caption for its ‘meaning’, and then go back to the painting and find new things in it.

RC. Yes, that’s exactly the way it’s meant to work.

NM. It is very much that, and also there are deliberately no titles for the pictures, other than the titles of the text. Again, we felt that the possibilities of the image would be much more if it wasn’t limited by something which tells you what it is.

JH. There’s a shift in perception brought about by looking back and forth between image and text. Like with Gams, which is number thirteen in the book – it’s a very striking image by itself, but as soon as you read about ‘Time's sherp gams' (‘Time’s sharp teeth’) you have to go back and reappraise those wicker spikes.

RC. Yes, each of them is recontextualising the other.

JH. Which I suppose also applies to the way that ancient and modern work together in the book?

RC. Yes, in the book there is an introductory essay which sets Simonides besides contemporary concerns about war casualties. In Edinburgh (where it was really an installation, I suppose, rather than an exhibition) the show was called Body Bags/Simonides. It took place in some studio spaces in the College of Art in Edinburgh, which had big windows that looked up to the rock and Edinburgh Castle on the top, which is a military barracks. So that was an interesting resonance. And on the floor in front of one of the windows there was an area of sand with four black body bags on it. So I suppose that gave a certain edge. In the book, the edge perhaps comes, to some extent, from the Introduction, which is called ‘Simonides and the War on Terror’. In the installation in Edinburgh there was nothing else to establish a connection with contemporary warfare. But these black bags did it. So that again was setting up a slightly unexpected context for people to read and view these ancient texts. I think that possibly one can exaggerate the general knowledge of Simonides. I think a lot of people don’t even know how to pronounce the word, let alone that this is the name of an ancient poet. So we were wanting to bridge that gap in a very immediate way, without having to have lots of explanatory matter, and just deliver the text and the photographs too.

NM. There is also a meditative aspect about the balance here, partly the sparseness of the texts that Robert’s been talking about. In the book this is to do with the layout, really. There’s a calmness, there’s a generosity of space – there’s not a lot happening. It’s designed to promote an ability to contemplate, to reflect, and that too has a resonance for the whole idea behind it.

.jpg)

Spartan War Dead, Thermopylae © Norman McBeath

RC. It’s about memorialization. It’s about how you speak of the dead, allowing them dignity and yet possibly also questioning what has happened. And I think that, especially the most famous of these epitaphs – the one for the Spartan Dead at Thermopylae that’s been translated over and over – my hunch is that when that’s quoted in Herodotus the lines have no irony. But I think it’s become impossible to read those lines now, without allowing for the possibility of some irony.

Ootlin, tell oor maisters this:

We lig here deid. We did as we were telt.

[‘Stranger, take this message to our masters: we lie here dead. We did as we were told.’]

The version in Scots is meant to allow for that irony to be part of the reading, but not necessarily for it to dominate the reading.

JH. How does it do that? I mean, how does the language of the Scots version encourage you to recognise the irony?

RC. I think simply ‘We did as we were telt’ is almost the kind of language that one might associate with being told to do something at school. With being somewhat unthinkingly dutiful. But it’s a question of trying to hint at that without over-toppling the poem, so that that becomes the only reading. Because I certainly don’t think that it is the only reading.

NM. Yes, and there’s been quite a bit of discussion about how that poem is best interpreted. I like this idea, as you say, of how this has changed as a consequence of recent events. There’s another edge to that.

JH. Thinking back to the Body Bags and the issue of memorialization, I wanted to ask Norman about the choice not to put actual human bodies in the photographs. It seems that there is instead a sort of ‘absent presence’ – either the presence of things that people have left behind, or bodies being referred to in a kind of metaphorical way, through the imagery of pieces of wood, or bottles….

NM. Well, there are a number of reasons for that. One key thing is this idea that we were talking about earlier – this idea of not being too literal, not being too definite about things. So there’s a bit of a journey to go there, to see what’s being referred to and to establish that link. So that’s one thing that was in my mind. But also, I think I’ve always been interested in human behaviour, in people, but particularly in the traces of what they’ve done – the evidence that’s been left afterwards. It seems to me far more mysterious, and again there are so many more possibilities that surround that. You have to speculate. You have to make some suppositions and judgments, and work out rather more. So I like the stuff that’s left behind, really. There’s clear evidence that something has happened, but it’s a much more open aspect about what that might be.

JH. It seems that some of your images could be set in any time and place - in Greece, or Scotland, or somewhere else altogether. Was that a conscious choice?

NM. Very much so.

RC. I think we wanted something that could be ancient and modern simultaneously. The medium of photography played into that, not least black and white photography. Although it’s clearly a modern medium there’s a certain timelessness that comes with black and white images, rather than with, say Ektachrome images.

NM. Yes, I think that’s very much the case. And that this timelessness worked very well with the idea of ancient and modern. Something that’s free-floating in the temporal sense. And as Robert has been saying, black and white particularly – there’s no real angle there; there’s no type of colour. It’s not Photoshop, or it’s not old colour. It’s very contemporary, but it’s also timeless. I don’t know if this is directly relevant, but this was also all done in film. And I think that the quality of prints that come from film as opposed to digital is rather special. There is a unique look to that which again fitted in well with the kind of thing that we were talking about.

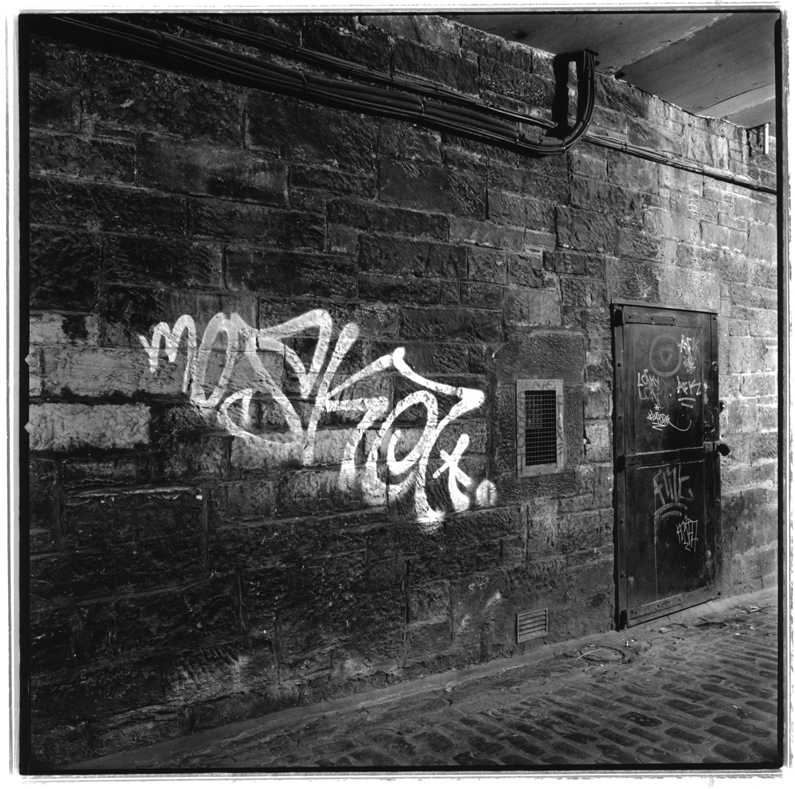

City © Norman McBeath

JH. What about these frames around the pictures in the book? Were they also visible in the exhibition?

NM. Yes, and again these were quite deliberate. In a way they testify that this is a full-frame print. There’s been no cropping – it’s exactly the same as what I saw down the camera. The camera is a square format Hasselblad so it’s quite a large negative – two and a quarter inches square. And when you print it, as the light is shone through the negative which is in the negative folder on the enlarger, if you’re not going to crop it you get these marks, which are little bits of light shining through. So each one has a unique thumbprint, as it were – these marks around the edges will be different, because when they are put into the carrier it’s a slightly different position each time. And so it’s a mark of authenticity, and it makes them also rather different from just square, cropped, neat pictures that are far more familiar.

JH. Robert mentioned earlier that you already had some of these photos when the collaboration started. But then did you go out and search for new images?

NM. Yes, that was the idea. We both knew that just in practical terms we really needed to have a few, just to make sure that this thing was going to work.

RC. We had to convince ourselves that it would work, and then have something to convince other people with. So in the beginning we had a sample of about half a dozen juxtaposed poems and photographs.

NM. And that gave us the confidence…there was absolutely no doubt then, in fact it was very reassuring that there was such harmony. I mean, if you’re going to have a collaboration there are lots of ways it can work, and it was really good to know that there was such a strong collaboration, and yet such flexibility. You know, there were lots of possibilities here, but we definitely had stuff that would work. And with that in mind, with that experience, Robert could then continue with the work on the text, and I could go out and get lots of pictures.

JH. So then was it a back and forth process, with each of you coming back to the other and showing him what you had done?

RC. Yes. There was a back and forth with Simonides as well, in a funny way, in as much as I found that only some of the poems and fragments I could do anything with. I just had to click with the material. I’m not meaning to pun ‘clicking’ with the camera! But you know, there was a sense of clicking all round, in that some of these ancient Greek poems or fragments seemed somehow to lend themselves to Scots, and the Scots in the poems is meant to sound….there’s a vernacular grain to it as well as a sense sometimes of using words that might be unfamiliar. So in a funny way the Scots too can float a little, in terms of time. Is it modern, or is it ancient? We’re not quite sure. And that was meant to go with what was happening in the photographs. And only sometimes was I able to feel that I could do something with that. There were some poems that I wanted to do something with and couldn’t.

NM. But then there was a great day when the text had been finished, and I’d done all the photographs, and we had them all laid out. I’d made small prints of all of them, and many more, and Robert had all the texts on paper, and we then matched them up. And it was a great day. Not only was it a great relief, but also…

RC. …there was an amazing amount of agreement.

NM. It was fantastic!

RC. I think that we were so used to working together and thinking about this by then that we just intuited what should fit.

NM. That’s right. And then once we’d got the matching, we then had to do some very careful editing in terms of the sequence. Because it was very important. I mean, if you’ve just got one photograph and one text, that’s fine, you can get a good match. Two – fine, bit more difficult. Three…the longer the sequence, the more redundancy there has to be, and the harder the editing. There’s only a certain number of pictures of X you can have.

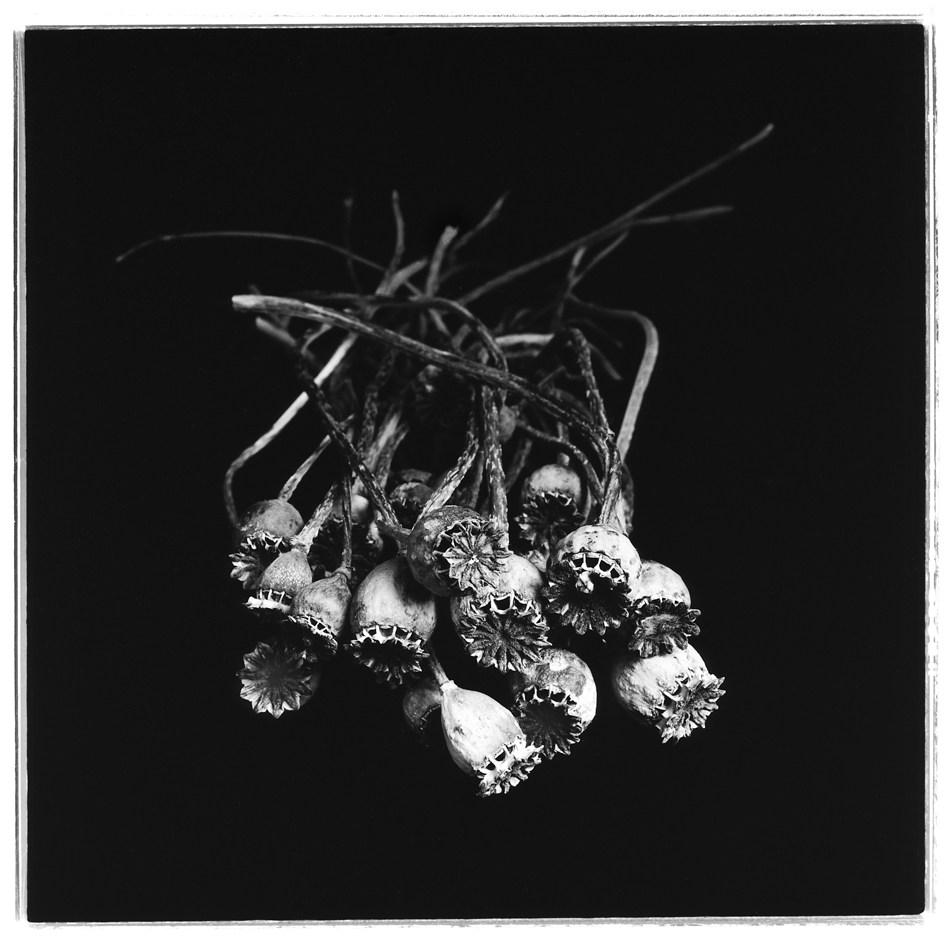

Yoam © Norman McBeath

JH. Yes, looking through the book you can definitely tell that it’s been assembled as a collection. For instance, there’s a balance between panoramas and tiny details of objects…

NM. Indeed, and where they appear in the series.

RC. We knew where we wanted it to end quite early on. We wanted it to end with a kind of wink, with this single word Dunter [‘Dolphin’]. Because some of it is pretty dark, and we didn’t want it to quite end that way. In a sense it ends by being eroded away to almost nothing, but significantly not nothing – something with life in it. Just as at the beginning there were those few lines about Orpheus, which are about light, which are about a kind of exaltation (in the poem it’s a rising up – there’s an excitement in it). We wanted that to be part of the sequence, and to be introduced quite early on, knowing that later there would be a lot of poems about dead people, about the fallen, but that wasn’t the only thing that was going on. So there was a kind of momentum.

NM. Yes, and thus Orphic aspect to the set is very important. It’s about light, and there’s singing, and that too is a balance to the sepulchral aspect.

JH. That’s probably my favourite image in the book. It’s so dizzy, and taken together with the mythological reference in the poem it makes me think of ancient Bacchic frenzies, and those images that you often see on classical relief sculptures of the maenad with her head tossed back in ecstasy. What about you both? Do you have particular favourite pairings of poems and photographs within the collection?

RC. I think I would pick the Ootlin poem, as Norman calls it – the one with the fallen trees.

NM. Which was also one of the very first. When Robert read that to me, that picture came straight into my mind.

RC. Yes, that was the right pairing. And something that struck me later, that I don’t think I was at all conscious of at the time, was when we sat down in a restaurant at some point with Edith Hall, the Homeric scholar. We were showing her the sample, and she said ‘You realise, of course, that fallen trees are an image of the dead in Homer?’ And neither of us – consciously at least – had twigged to that. But when she said it, that was great. That was confirmation. We knew that was the right pairing before, but that strengthened it, so we knew that we were on the right track.

NM. It’s very difficult for me to pick one, but perhaps it would be this one – Bonnie Fechters. The poem goes

‘Fareweel, bonnie fechters, aa faur kent

Athenian laddies, handy wi yir cuddies,

Wha gied yir youthheid aince, for yir cauf kintra,

Fechtin maist o the Greeks, agin the odds.’

[‘Farewell, splendid fighters, all far-famed, Athenian youths skilled with your horses, who sacrificed

your young lives once, on behalf of your native land, fighting most of the Greeks, against the odds.’]

The photograph shows bottles in an old dovecote in the back of a farmhouse. I was thinking about wood and bones when I saw this, and I thought it was just like those tombs in Venice, where there are those bits with the bodies in there and maybe a photograph and stuff. And so I thought about that, and once again it just seemed absolutely right. But I learned afterwards that the French call these empty wine bottles cadavres, so that was another thing. Also, you can see that there’s a Bell’s whisky bottle in the centre. When I was doing the test strip for this print I was homing in on just this bit, and they have this wee label round the neck with this Simonodean phrase ‘Afore ye go’. The double meaning was just so perfect. That’s always what they do in Scotland, you know: ‘Oh, before you go you better have another one’! It was just right. And I think that must be one of my favourites.

JH. Before we go, I wanted to ask one more question, this time about the ‘invisible third person’ in the collaboration – Simonides himself. Perhaps I could ask each of you to tell us what Simonides has brought you, as a creative artist working in the twenty-first century?

RC. For me, I think it is a sense of tremendous concentration on what is important. A sense of honing, which the process of history and loss and erosion has intensified, but which surely is there in the epitaphs from the start. This is something expensive, to have these epitaphs carved, to have them commissioned. For me, some of the stories about Simonides and meanness are about the valuing of poetry – that poetry matters, that poetry is, in the best sense of the word, priceless. So I was interested in all that about Simonides. But especially in this very honed articulation of memory, memorialization and loss, which was immediately, powerfully emotional. And the more I worked on the poems, the more I thought ‘This is wonderful’.

NM. Well, that would cover a lot of what I thought too! For me, he’s been a great opportunity to learn about that period in history, and what this particular man has done, in terms of being one of the first people really to insist on the idea of commissioning art. You know, if he’s going to write stuff, it’s no longer going to be trading favours. It’s actual cash, cash for things, first coming in when he was around. But like Robert, I like the permanence and the seriousness of this work. And I like the fact that he was talking about bits of ordinary peoples’ lives, really, and marking that. There’s also a kind of diary aspect to it that characterises normal people, and that particularly impressed me. It also fitted in with using photographs that are about normal life in this context.

JH. That’s wonderful. Thank you so much to you both for taking the time to talk to me about your work, and for sharing all of these fascinating insights into the processes of collaboration.

Find out more...

Copies of the Simonides book can be bought through Easel Press

You can read more about Norman McBeath's work on his website

Details of Robert Crawford’s other publications can be found on his University of St Andrews webpage