Practitioners' Voices in Classical Reception Studies

ISSN 1756-5049

You are here

- Home

- Past Issues

- Issue 8 (2017)

- Rachael Lloyd

Rachael Lloyd

Chrissy Combes spoke to Rachael Lloyd about The Day After at Lilian Baylis House, West Hampstead.

The production photographs from ‘The Day After’ are by Fiona Rich. In addition to being a photographer Fiona is a singer who has been a member of the English National Opera chorus for 31 years (singing under the name Fiona Canfield). All photographs are copyright. Photographic captions are taken from the libretto of ‘The Day After’ by the playwright April de Angelis.

Audio extracts from the interview can be found on the Open University podcast site.

A PDF copy of this interview is also available for download.

CC. I am talking today to the mezzo soprano Rachael Lloyd at Liilian Baylis House, which is the rehearsal studio of the English National Opera. Rachael is enjoying a varied career in both opera house and concert hall. She has sung at Glyndebourne, she sings regularly with the English National Opera and she sings with the Royal Opera. Among her most recent credits, she has sung the title role in a production of Bizet’s Carmen at the Royal Albert Hall, the role of Piiti-Sing in one of the many revivals of Jonathan Miller’s ENO production of The Mikado (a revival which also starred Fiona Canfield as Peep-Bo) and the role of Third Lady in Simon McBurney’s production of The Magic Flute, also with the ENO. Last year, Rachael sang the role of Alisa in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor in the production by Katie Mitchell at the Royal Opera House and she is singing this role again in a revival of the production this autumn. This summer, Rachael sang the dual role of Woman and Mother in the UK premiere of The Day After, the opera composed by Jonathan Dove with a libretto by April de Angelis. Rachael, you’re a very busy person, thank you for talking to me today about The Day After.

RL. You’re welcome.

CC. Could you tell us, just to begin with, why there was an ENO production at the Lilian Baylis Studios? The ENO home is usually the Coliseum on St Martin’s Lane.

RL. Exactly. But this is a new initiative set up by English National Opera which is called ENO Studio Live which has come about really to give audiences the experience of seeing the English National Opera chorus and emerging young artists and in-house artists as well in a studio environment – so ‘up close and personal’. Also the Coliseum currently gets rented out for a quarter of the year to big shows (they’ve had Carousel in there this year) and it gives the company a chance to do things elsewhere, which is good. It gives more accessibility, I think. No one really knew whether it (the ENO Studio Live venture) was going to work or not, to be honest. I think everyone would put their hands up and say that. But everyone was very keen to try. There was a lot of repainting done on the interior here in Studio 3 and new chairs ordered to make it a comfortable, acceptable venue for audiences and it has worked brilliantly. Also, although intimate, this space at the Lilian Baylis House is a decent studio size.

CC. The Lilian Baylis House is the historic ENO rehearsal venue, named for the ENO founder, Lilian Baylis, isn’t it? And the initiative here came about under the new Artistic Director Daniel Kramer?

RL. Yes, that’s right.

CC. The night I saw the production, it was a packed house here.

RL. Oh, every night. It was a very exciting experience.

CC. An end-on staging for this production?

RL. Yes.

CC. With the ENO chorus mainly on either side?

RL. On either side, yes. There was a raised platform area centre-stage where the five principals spent most of the time, and occasionally the chorus would come up and join us in that area.

CC. Might I ask you a little bit about Jonathan Dove? I remember seeing his opera Flight in 1999 (also with a libretto by April de Angelis) at Glyndebourne and was greatly impressed by it. And he is such a prolific composer. He seems to me to write wonderfully for the voice. Is it grateful music to sing?

RL. It’s really grateful music to sing. He really is an expert in writing for the voice. And also he makes it musically very accessible, I think, without it necessarily being simple. You know, I had a few friends who came to see the production who really don’t go to opera at all and who have no particular interest in classical music and they all absolutely loved it, they were really taken aback. Jonathan writes very, very well, and it’s often beautiful. I think so often now with contemporary composers it’s all about the difficulty of the music and sometimes that loses the beauty of what music can do.

CC. The work seemed very tonal and very lyrical?

RL. But very original to him. You know, he really has his own style. It’s not just pastiches of various other composers.

CC. Was Jonathan Dove present at rehearsals at all?

RL. Yes, he was there a lot. He was there on the first day, for the first music call. Then he probably wasn’t in for the next ten days or so until we had really got the production established (because we only had three weeks to do the whole thing) and then once we were into properly being onstage he came back and he was there for a good week and I think he came to three out of the four shows as well.

CC. Oh did he?

RL. Yes, and I think he was very happy with it.

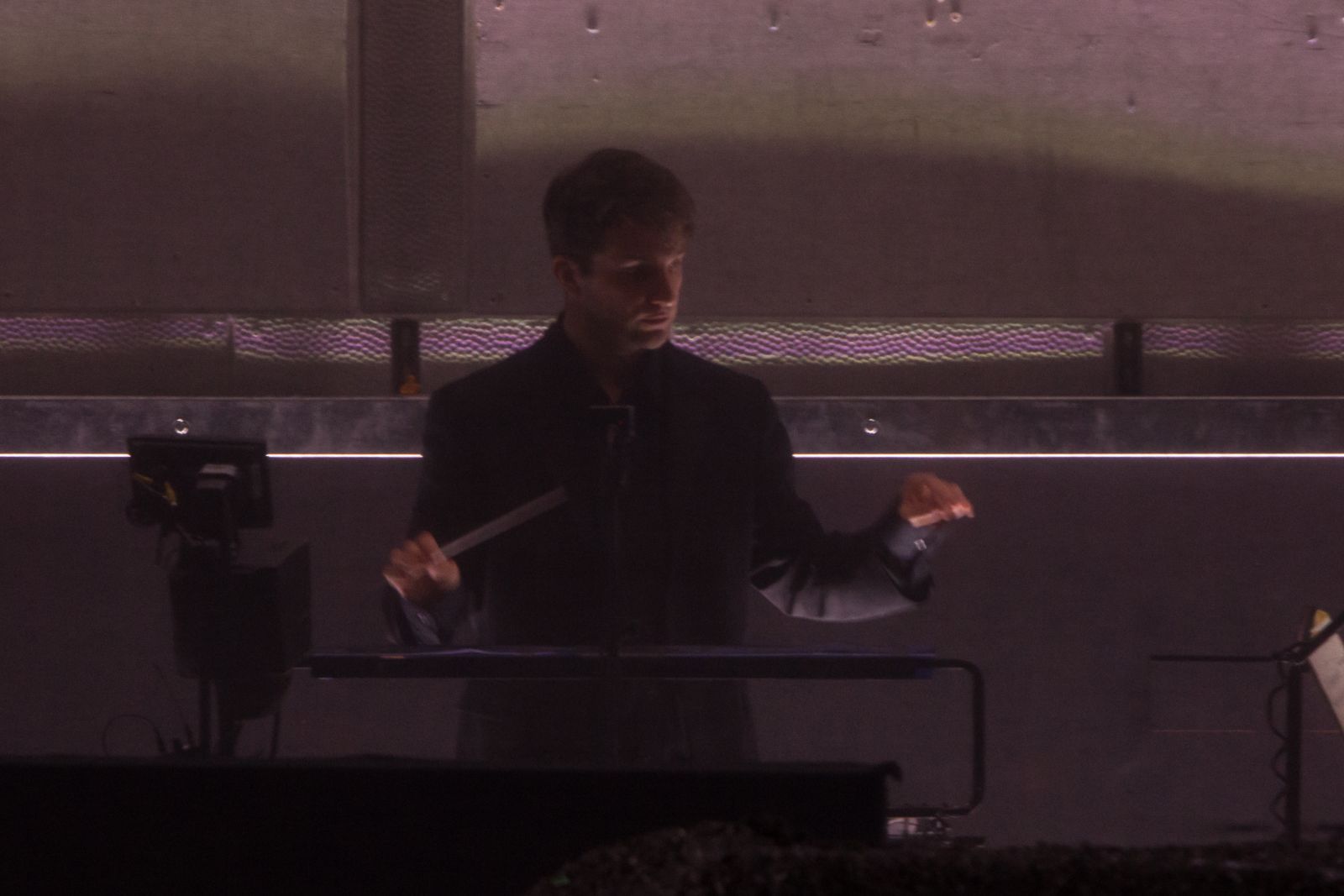

CC. At first I thought he was conducting, but he wasn’t, was he? The conductor was behind a gauze, so it was a bit difficult to see who it was.

RL. No, it was James Henshaw. Who is actually the Chorus Master of English National Opera. But also he works as a conductor in his own right.

James Henshaw conducting ‘The Day After’

CC. So this opera, with the intriguing title The Day After is based on the story of Phaeton, originally from Greek myth, and as depicted in Ovid’s Metamorphosis, isn’t it?

RL. Yes, that’s right.

CC. Could we look at where the opera follows Greek myth and particularly Ovid? In Book 2 of Metamorphoses Ovid describes how Phaeton is challenged by his playmates as to whether his father is really the Sun god Phoebus. Phaeton goes to his mother, Clymene, who confirms that his father is Phoebus, whereupon Phaeton visits the palace of the sun god and Phoebus pledges to give him whatever he wants. Phaeton’s wish is to ride his father’s chariot, the chariot that pulls the sun across the sky from east to west. His father is horrified by this suggestion but Phaeton insists on driving the chariot, takes the horses’ reins and eventually loses control so that the chariot plummets close to the earth which becomes in danger of completely burning up. To save the earth, Zeus sends a thunderbolt that kills Phaeton and the young man falls into the river Eridanus. His mother mourns him and his sisters grieve for him, turning into poplar trees and weeping tears of amber. How did the libretto differ? Could you tell us what April de Angelis’ narrative is?

RL. Well, the opera is set almost in two different times. The mythology of it is set as a past memory. And it’s called The Day After because it’s a post-apocalyptic setting. A great disaster has happened and the opera opens with everybody crowded on a black earth mound, an ash mound. There’s no natural daylight. Jamie [director Jamie Manton] and Camilla [designer Camilla Clarke] came up with the idea of having a harsh stadium light on a crane which came over the stage and gave everybody their daylight in an environment where the air was just so thick with black ash that no sun could penetrate through it. The idea was we were living in total darkness. And the opera opens with the five principal characters coming back from scavenging. Everybody has gone off to try and find some food. Everyone is saying how desperately hungry they are, there’s a big choral section about that. ‘Dream of before sharpens its claws on a hungry belly.’ They are desperate and starving. And all they have found is a few grains of rice and a dead cat with maggots falling out of it.

‘Dream of before sharpens its claws on a hungry belly’. The opening scene from ‘The Day After’.

CC. So the opera doesn’t begin directly with the story of Phoebus and Phaeton?

RL. No, not directly. But clearly there has been a catastrophe where the earth has been almost annihilated and everyone is completely traumatised. Then, eventually, it gets to the point where, for a bit of light relief, to take them away from their current situation, the characters ask the woman (my character) to re-tell the story of how this has happened, how they got in this situation. ‘Tell us, tell us, tell us, tell us again.’ And so she then transforms from the Woman into Phaeton’s Mother.

CC. So it is a kind of tale within a tale? A contemporary tragedy arising from the mythological story?

‘Tell us, tell us, tell us, tell us again.’ Rachael Lloyd (centre).

RL. That’s right. The action transfers into the story of Phaeton and Phoebus. But it’s interesting because there’s no sense of what time has passed between Phaeton crashing the chariot of fire and the situation that the characters are in now. There’s no sense given in the score or libretto of how much time has passed. And costume was not from any ancient period or Greek mythology – it was very much modernish dress and everyone very tattered and ragged. I suppose in a sense no real time was established. And then you go through the whole story of Phaeton and in the end it snaps back out to a post-apocalyptic context again. And so Phaeton who is the Young Man at the beginning turns back into the Young Man again at the close. And I thought Jamie, Jamie Manton, the director, was very clever in the way he staged the changes. He made the transitions very clear.

CC. There is extraordinary relevance of this myth to our contemporary period, when the planet is threatened by global warming and nuclear devastation. And this was really emphasised by the libretto, I thought.

RL. Yes, before we started the project, Jamie sent us some video clips to watch, things he wanted us to watch before we turned up to rehearsals, and there was no Greek mythology in that. There were very much things about Hiroshima we watched, things about global warming, so his ideas behind it were very much apocalyptic things that could happen now, rather than reference to Greek mythology or epic poetry.

CC. You mentioned five principal characters. Could you talk a little bit more about who the five main characters were?

RL. So, in the initial opening, the opening scene, nobody has any name. It was just Old Woman played by Susanna Tudor-Thomas, Young Woman played by Claire Mitcher, I was Woman, and then you had Young Man (tenor Will Morgan) and Old Man (Robert Winslade Anderson). And the Old Woman and the Young Woman never change, even though they take part in the Greek mythology about Phaeton, they are still down in the score as Old Woman and Young Woman, they don’t take on another persona. And then for me, the Woman turns to the Mother, and the Old Man turns into Phoebus and the Young Man turns into Phaeton. And actually three out of the five principals are from the Chorus.

CC. Oh really?

RL. Yes, it was only myself and Will Morgan who are outside working principals.

CC. And what was very interesting was that when some of the action was taking place with the five principal characters, the Chorus were echoing that action, weren’t they?

RL. Well Jonathan Dove really wrote them like a Greek chorus, commenting on the action that was going on onstage a lot of the time. The world première of the opera was an open-air production by Holland Opera in 2015. But in the Holland Opera production there was no chorus, just the five characters. Jonathan Dove wrote the chorus especially for our production, specifically for the English National Opera chorus. It’s a new choral version of the opera.

CC. I have seen video clips of the Holland Opera production. It was on a huge scale, lots of technical effects and spectacular use of fire. Completely different in tone from the English National Opera version, which was simple, more suggested. Yet although Camilla Clarke’s design was sparing in use of props and scenery, she still created a dark, bleak, post-apocalyptic atmosphere. So clever.

RL. Oh, a great design. And throughout the whole opera the chorus helped to establish that sense of terror, that sense of suffocation, for instance, with ‘Hot ash instead of air. Can you taste our fear?’

‘Hot ash instead of air’. Members of the ENO Chorus.

‘Can you taste our fear?’ Members of the ENO Chorus.

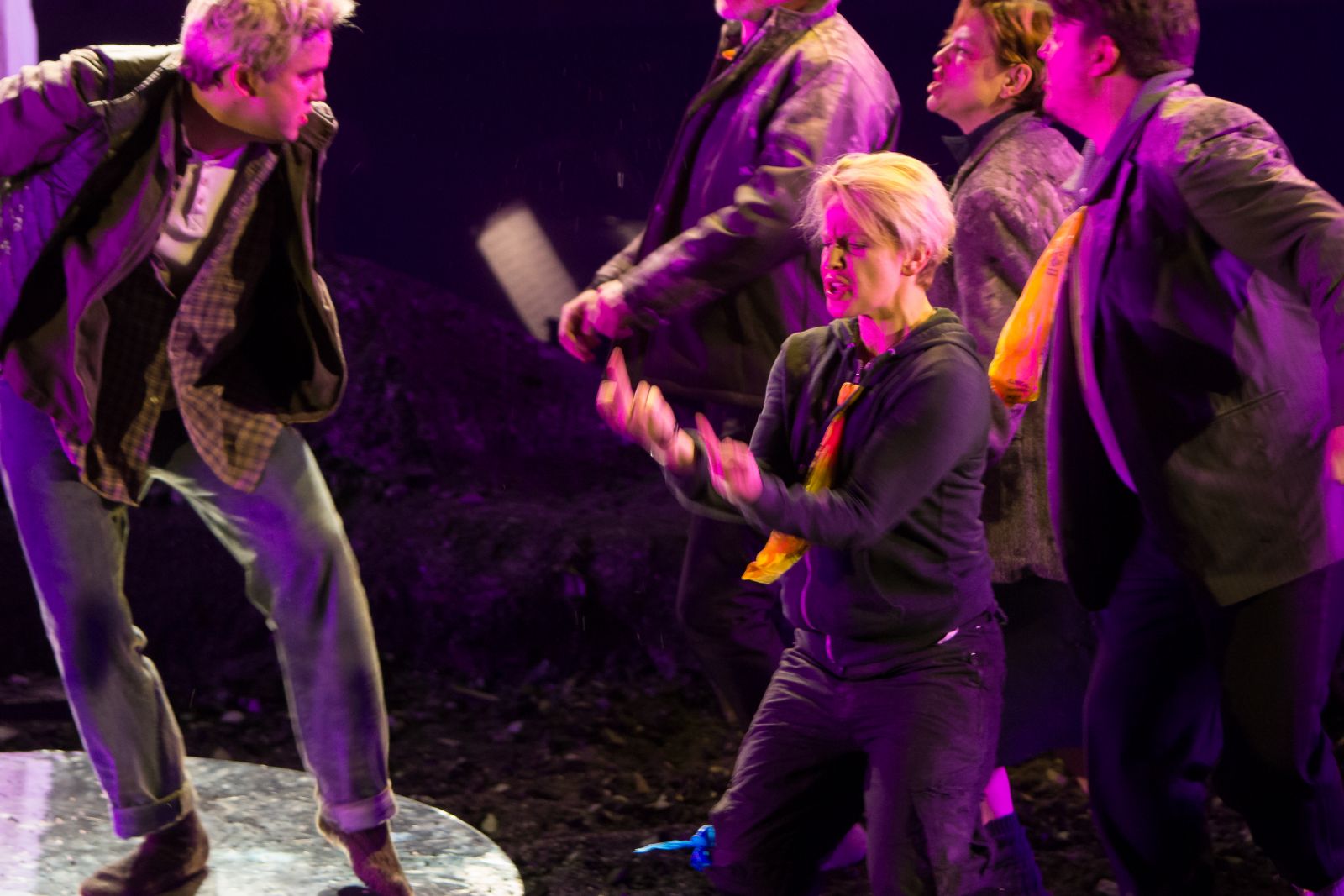

CC. And when you began to retell the story of Phaeton, some of the chorus became school playmates who were teasing him about his divine sonship. Fantastic acting skills.

‘Your lordship! Prince Phaeton!’ Members of the ENO chorus jeer at Phaeton (Will Morgan) left.

RL. Yes. So this was a really good scene. Phaeton was in a schoolyard. And about eight of the chorus came on to be the schoolchildren who were bullying him. Very contemporary in its libretto and its language. Slightly lewd! But, you know, in that sense quite realistic, what a teenager might experience when being bullied in a playground. They called him ‘Your lordship’ and ‘Prince Phaeton’ and asked him if and when he was going to his palace. Phaeton had clearly been boasting to them!

CC. And your character has chosen the character of the Young Man to play Phaeton?

‘Going to your palace?’ Phaeton (Will Morgan) on the ground while members of the ENO chorus mock him.

RL. Yes, that is the point. The Woman chooses him to play the part. This is the thing. The Young Man is not Phaeton. The Woman is not Clymene. She has been asked to re-tell the story. The Woman as the leader of the camp takes on the responsibility to play Clymene and she chooses the Young Man to play Phaeton. I take off his beanie hat so that he makes the switch from being Young Man to being Phaeton and I simply take off my old coat to switch from being Woman to being Clymene. I am wearing a vaguely classical type dress underneath the coat.

CC. So you’re acting it out really?

RL. Yes, it is all just acting out the situation.

CC. So is the ‘day after’ what has happened in the Phaeton story or is it that time is loose and it is more the contemporary catastrophe?

RL. I think there is no sense of time really. But, if anything, it is both time periods combined.

CC. Then after the playground bullying Phaeton goes to see his father in the palace of the sun?

RL. Yes, actually after the bullying, he has angrily spoken to his mother and said to her ‘Why have you always told me that I’m the son of a god? And she turns round and reveals to him: ‘Your father IS a god’. So after the ill treatment from his playmates, he decides to visit Phoebus.

CC. She doesn’t want him to go, does she? But she knows he will. She sings something about breaking her heart, very movingly. I notice with April de Angelis’ libretto – it can be quite terse then you suddenly hear very beautiful poetic language and Jonathan Dove’s haunting music fully conveys that beauty. It’s a real marriage of lyric and music.

RL. Yes, he sings... It’s after the bullying.... She says ‘What’s happened?’ He says ‘Nothing.’ ‘Bullied again?’ He sings ‘Don’t fuss. woman, leave me alone.’ She says: ‘I’m a lioness, touch my cub, I’ll rip them to shreds.’ He sings ‘Mum, I’m not dead. No thanks to you.’ ‘Me? What did I do?’ ‘Leave it, leave it.’ And then the bit that you like: ‘No, finish what you start. Break my heart.’

CC. And then a scene where you are back to back with Phoebus and you are facing the audience? Lovely and hypnotic music.

RL. Yes, that’s when I’m telling Phaeton about how I met Phoebus for the first time.

CC. Could you give us a few notes from that aria?

‘I met a stranger.’ Rachael Lloyd (Clymene) and Robert Winslade Anderson (Phoebus).

RL. What, in terms of singing? Oh God, I haven’t warmed up yet. OK (Sings):

‘I met a stranger

I met a stranger

I met a stranger

One Night’

CC. Beautiful, absolutely beautiful.

RL. It’s very nice.

CC. You’re remembering your meeting with the god.

RL. Mmm. And she sings ‘His eyes burned’.

CC. And then the Old Woman and the Young Woman join you? A communal storytelling.

RL. Yes, they are saying how the story began and helping to tell the story all the time.

‘That’s how the story began.’ Clymene holds the baby Phaeton. Behind, left to right: Old Woman (Susanna Tudor-Thomas), Phoebus (Robert Winslade Anderson) and Young Woman (Claire Mitcher)

CC. So when Phaeton is reassured that Phoebus is his father he decides to make the journey to visit him in the palace of the sun?

RL. Yes, off he goes. He sings ‘I want to see the god of the sun.’ And the libretto gives a beautiful description of his long journey to the east.

‘I want to see the god of the sun.’ Will Morgan as Phoebus

CC. Does Clymene have a sense of foreboding? Is she sad about him leaving?

RL. Well he is a golden boy in her eyes, she is incredibly protective of him. She is apprehensive and the ‘break my heart’ is because he is blaming her and not believing what she is saying. But there is never really a point where you will see her regret about what happens to him. In the opera I have a kind of third role in the Greek chorus of three women – who actually become the three horses during the chariot ride. And only then perhaps does she occasionally break out of the chorus/horse role and then there are a couple of lines when she says, as the Mother, ‘Think of me, think of me.’

CC. Robert Winslade Anderson has great presence as Phoebus.

‘I am Phoebus, God of the Sun.’ Robert Winslade Anderson as Phoebus.

RL. Oh, a marvellous performance.

CC. I was so surprised to see the singer costumed as he was. Ovid, in Metamorphoses, gives a very detailed description of the palace of the sun as a golden, bright, towering palace, and Phoebus is portrayed as wearing a purple robe and a crown of glittering rays, and sitting on an emerald encrusted throne. There seemed no attempt to convey anything of this visually in the production, here was Phoebus wearing high visibility overalls! Yet Robert Winslade Anderson gave such a commanding, powerful performance and has such a deep, beautiful bass baritone voice, you completely believed him when he sang ‘I am Phoebus, God of the Sun.’

RL. The chorus sing about the cool marble of the palace. And I hope you noticed that Phoebus was wearing a crisp white shirt and a gold tie under his boiler suit!

CC. I did! Phoebus isn’t receptive to Phaeton at first, is he?

RL. No, he doesn’t know who he is. But then Phaeton uses my name. ‘My mother told me. Her name is Clymene.’ And at that point Phoebus remembers.

CC. Very beautiful, very beautiful, again from what I remember. ‘I loved her. I loved her.’

RL. Yes. ‘I loved her, I loved her long ago.’

CC. And then you come in again, don’t you?

RL. Then I come in, yes.

CC. And that was one of the most moving scenes. Could you describe that scene for us?

RL. So, when Phaeton goes in to the palace of the sun, as I have said, the three ladies almost become like a Greek chorus at the side. And then as soon as Phaeton brings in Clymene he points to me as he says ‘Clymene’ and I break out again of the chorus and become Clymene again. There’s a large mirror in the centre of the mound, a round mirror that is used, and that’s the point where I have changed the Young Man into Phaeton and it’s also the point where I move forward as Clymene again and I take my place on the mirror, not frozen but quite statue-like to begin with. Phoebus sings his lovely aria, saying he loved me long ago, encircling me on the mirror. It is after that he confirms to Phaeton that he is the young man’s father, and promises to give him anything he desires as a token of Phaeton being his son. He swears by the mighty river Styx and by the stars and the planets. ‘Ask, it shall be yours.’ Upon which, Phaeton is unbelievably excited. Will Morgan, as Phaeton, conveyed that excitement and anticipation so well. But when Phaeton asks to drive the chariot of fire we three ladies are singing ‘Tell him No. Don’t let him do it!’

‘Ask, it shall be yours.’ Will Morgan as Phaeton and Robert Winslade Anderson as Phoebus.

CC. Then the horror unfolds, doesn’t it? Phoebus realises that the promise to give Phaeton whatever he desires is a fatal promise. Because the young man asks to guide the sun chariot for a day, and cannot be dissuaded. Phoebus is very reluctant to yield to Phaeton because he knows that the boy will not have the power to control the horses pulling the chariot, but Phaeton insists.

RL. Yes. Phoebus warns Phaeton that he will be too weak to control the powerful horses, but has to give in to him.

CC. And once more, there was a surprise awaiting the audience. In Metamorphoses Ovid is again very detailed in his description of the chariot. It is a thing of beautiful workmanship, the wheels have golden rims and silver spokes, and it is studded with gemstones and glowing with light, while the horses (four of them in the poem) are fiery and swift, and have ringing harnesses. However, in the production, the chariot and the horses are created very simply and very imaginatively. Can you describe the chariot a little bit? I was quite shocked by that when I first saw it.

RL. The chariot is quite simply a wheelchair. It’s just a wheelchair that was left on the side of the ashen mound. And the horses that pulled Phaeton were myself and the other two ladies. We put on gas masks and simply picked up the cables to draw the chariot. Will (Phaeton) stood on the wheelchair. Occasionally we become the Greek chorus, warning Phaeton, but he won’t listen. He calls himself ‘King of the sky’ but we are warning him ‘You will die!’

‘You will die.’ Left to right: Old Woman (Susanna Tudor-Thomas), Mother (Rachael Lloyd), Young Woman (Claire Mitcher).

‘King of the Sky!’ Will Morgan as Phaeton (right).

CC. Did you know you were going to play a horse?

RL. No, I never thought I would – it was, you know, an experience!

CC. There was such clever choreography based on you three being attached to those big electricity cables. It was so effective, really strong. The costumes, the lighting, the movement, the singing, all came together to make the audience completely engage with the idea of the boy being pulled in the chariot across the sky, making a mad and dangerous journey from east to west. The choreography was extraordinary, very muscular, repetitive movement from those horses. The chorus were singing about ‘The horses pounding the ground.’ And that was certainly the movement you were conveying.

‘The horses pounding the ground.’ Left to Right: Rachael Lloyd, Susanna Tudor-Thomas and Claire Mitcher.

RL. It was very good, very good choreography by Jasmine Ricketts. Really good choreography. It looks quite simple, and yet really wasn’t. It took a long time to work out, I think because it was quite slow choreography it was actually more difficult. Yes. And, as I said, our reins were long electricity cables that came over our shoulders and our horse element were the gas masks.

CC. It’s the climax of the whole thing, isn’t it, theatrically and dramatically and musically, the riding of the chariot?

RL. Mmm, the riding of the chariot. And the orchestration of that is amazing.

CC. Would you describe that orchestration for us?

‘Faster! Faster!’ Phaeton (Will Morgan) urges the horses on while Phoebus (Robert Winslade Anderson) watches.

RL. So the orchestra (the ENO orchestra) was actually behind the stage, behind a gauze. It was quite difficult for James, the conductor, because he was behind all of us. But he had monitors and we obviously had monitors but it meant a slight lack of contact for him. But the orchestration is mainly brass and wind, flute, oboe, clarinet, soprano saxophone, bassoon, two horns, two trumpets, a tenor and a bass trombone. Then there’s a harp and a double bass, the two stringed instruments, and then there is the most amazing amount of percussion, four timpani drums, wood blocks, maracas, djembe, congas, tambourine, tom-toms, suspended cymbal…the list just goes on and on. It is a huge percussion piece. But in the chariot scene, Jonathan Dove writes the most amazing five-bar, six-bar repeated rhythmic section. It’s very cool. Really good with the brass there too. It’s very effective.

CC. And you’re doing the horses, over and over again.

RL. And we’re doing the horses, exhausting. While Phaeton is singing ‘Faster! Faster!’

CC. It was a stunning effect. And with the music and the eerie lighting you forgot the wheelchair and you believed that this brash young daredevil was on a chariot. And Will Morgan as Phaeton was remarkable. Not only in his wonderful singing but also his animated expression, every muscle in his body, conveyed the character’s belief that he had taken on the power of a god and was controlling nature. And that music and libretto! I remember one of his lines was ‘It’s me in the heavens, extinguishing the stars.’

‘It’s me in the heavens, Extinguishing the stars.’ Will Morgan as Phaeton riding the chariot.

RL. Will was superb. And the chorus added so much to this section, singing with the protagonists, helping to establish the danger of the situation to all humankind. They sang ’We have daughters, we have sons. Make him pay the price.’

CC. It was extremely powerful to see them and to hear them.

‘We have daughters, we have sons. Make him pay the price.’ Members of the ENO Chorus.

RL. The chorus were extraordinary. They brought so much to the emotion of the piece.

CC. And so, suddenly, during Phaeton’s mad dash through the sky, he realises that he has lost control of the horses, they run wild. Ovid describes how they climb to the heights of heaven, then rush precipitously towards the earth, dragging the sun towards the earth which bursts into flames. In the Greek myth and indeed in Metamorphoses it is Zeus who sends the thunderbolt that strikes Phaeton down, in order to save the earth. Ovid says the thunderbolt removes Phaeton from the chariot and from life. In the opera it is Phoebus himself who sends the thunderbolt, isn’t it?

RL. Yes, he makes the decision that the only way he can stop this is to send the thunderbolt down and kill his son. Reins are wrenching Phaeton’s arms, the earth is being completely scorched.

CC. Very difficult to stage such a death. Can you remind me how this was done?

RL. Basically the death was staged by the horses turning back into women and pulling the electricity cables so it looked as if he had lost control, but also as if he died in an electric chair. Then Phaeton fell to the floor. Yes, it was difficult to do, because it was all slightly in slow motion and the lighting was the only effect there was. And afterwards, after he was dead on the floor, there was blood, black gunk that came out of his mouth. Then there was a wonderful silence and just a very deep bass note running and we three women, having fallen to the floor too, slowly sat up and started singing in a trio, one after the other in a canon: ‘There he tumbles down, Like a feather, like a stone’.

‘There he tumbles down, like a feather, like a stone.’ Young Woman (Claire Mitcher), Old Woman (Susanna Tudor-Thomas) and Mother (Rachael Lloyd).

CC. These were absolutely chilling moments. And Phoebus was seen to be stricken with grief at the death of his son. Would you have said that the ending had any hope in it after this catastrophe, these terrible events have unfolded?

RL. I think maybe at the very end, there’s just a little glimmer. After Phaeton dies the action then switches back into the present and we go back to being who we were at the beginning. There’s a kind of transition where we are starting to go back into the original people but Phoebus is still there and he sings: ‘How will I drive the sun now when I have no son? I can do without the light, without the day.’ And then it almost snaps back and the Old Woman says ‘We can’t.’ And I say: ‘That’s the story.’ And then that was the moment when I handed the beanie hat back to Phaeton to become the Young Man again and he said ‘For a moment we were back before. And now this. A land of rags and rust, ghosts, dust.’ And then it goes into a beautiful big choral canon: ‘No home, no child, no lemons, no lilies, no chairs.’ Very quiet, very sombre. And then it’s just at the end, I think (because that is all quite heartbreaking, that final section) just at the end, the very end, you have a moment between the Young Woman and the Young Man. Because in this production the Young Woman is very heavily scarred on her face, she has obviously had some big accident from the event, and just at the end of the choral section the stadium light begins to fade, as if we have run out of power and it’s all going back into total darkness, and she has her torch which she holds onto the mirror so the audience can see her looking at herself in the mirror and the Young Man looks at her and says ‘You’re beautiful’ and she says ‘No. No.’ And he says ‘Yes. Beautiful as a new day.’

‘Beautiful as a new day.’ Young Woman(Claire Mitcher).

CC. Oh yes, I remember that moment. The chorus had been singing: ‘No views, no roads, no fish, no butterflies’ over and over again, in complete desolation. Then the opera ended on just that faint, touching moment of hope for the future of humanity. But the night I was there, and I’m sure, on the other nights, there was such a silence at the end before the applause.

RL. Quite a scary silence for a performer!

CC. It really was, wasn’t it?

RL. I thought ‘Did they just like that? Or did they hate it?’ Do you not agree? When the silence was so long.... ‘Are they not clapping because they’re not sure?

CC. We were very shocked.

RL. That was it though. Everybody said that. I think it was because…. You have to remember that this is only an hour and a quarter, this piece. There is no interval, it just runs straight through. And the text and the orchestration are very dynamic, and I think it’s a lot for an audience member to take in in an hour and a quarter. And I think people left thinking ‘Oh goodness, what did we just experience there?’ A lot of people were left quite affected by it.

CC. And the relevance as well. The reality of a young man as if saying to his father ‘Can I borrow your fast car?’ And then catastrophe, an accident. But much more than that.

RL. Well it’s just the recklessness of it, isn’t it? One man’s recklessness that could have an effect on the whole world. Which, I mean, actually, is very relevant, you know, today.

CC. Precisely. We won’t mention names at all! About American presidents. At all!

RL. Not At all. We wouldn’t want to do that! Just in case.

CC. No reference to North Korean leaders either! But in all seriousness, the opera raises huge and disturbing questions about hubris and ambition and reckless decisions and about how all that can threaten the earth and the human condition. (As, of course, does the story as told by Ovid). There is such a particular resonance today, with the dangers of global warming, climate change, the death of species, the destruction of the environment, and the threat of nuclear war. However, was the production a happy experience for you as a performer?

RL. It was an amazing experience. For everybody. English National Opera have had a really difficult time over the past few years, you know when they had their Arts Council funding withdrawn – which they have just had reinstated. Wonderful news. And they absolutely deserve it as a company. They have had a very difficult few years, and I think coming in to such a small context, being in a small, simple space, was in a way almost going back to simpler things.

CC. As if back at Sadler’s Wells, I guess?

RL. Yes, almost. And, incredibly, this was the first opera Jamie Manton had ever directed in its entirety. He works as a staff director with English National Opera so he assists on a lot of big productions but this was the first show that was absolutely his. And he was amazing.

CC. It was beautifully directed and staged, an enriching experience for the audience.

RL. He was amazing. He was so clear and precise, it was so well thought out, he knew the score so well. It was really impressive. And he is only 25, I think. He is definitely a talent to watch. And the atmosphere was so lovely. There were no big egos in the room to contend with and very often there is at least one at that kind of level.

CC. Happy rehearsals?

RL. Really happy rehearsals. And the chorus said to me, a lot of the singers who have been in the chorus for years, for decades, said to me: ‘It kind of feels like the old days, doing this.’ It just brought a lot of happiness to everybody. And as far as I know, I know management were really happy, because there was also Trial By Jury, which was the other show staged under ENO Studio Live - a total contrast! (Unfortunately, I didn’t get to see it). And it was also a great success.

CC. Did the chorus play in both?

RL. Yes, they played in both. And I know everyone involved seemed really happy with the whole concept of ENO Studio Live, the whole idea, and I think it will definitely be returning next year.

CC. It’s a terrific concept, and The Day After is a beautiful, deeply significant opera. And I loved the experience of being so close to the action and being able to appreciate not only the astonishing singing from the principals but also the magnificent power and beauty of the ENO chorus in full force. I can see why in 2016 – at the height of those difficulties you mention, Rachael – the ENO Chorus and Orchestra won the Laurence Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement in Opera. It was such an astute judgement on the part of the Society of London Theatre opera panel, giving the award to this great, professional operatic ensemble. Rachael, thank you very much for talking to me today about The Day After – a production which was also, in every sense, an outstanding achievement in opera. Long live ENO Studio Live!

RL. Absolutely! Thank you Chrissy. You are really welcome. I have loved talking to you.