Practitioners' Voices in Classical Reception Studies

ISSN 1756-5049

You are here

- Home

- Franco Murer

Franco Murer

Franco Murer (b. 1952) is a painter and sculptor, who lives and works in his birthplace of Falcade in the Italian Dolomites. Growing up, he learned sculpture and painting alongside his father, the artist Augusto Murer, before studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice, from which he graduated in 1974. His vast oeuvre includes drawing, painting, and sculptures in different media, including wood and bronze. Much of his work centres on Christian subjects, and examples of his sculptures can be seen in the Vatican – such as his monumental fountain decorated with scenes from the life of St Joseph, dedicated to Pope Benedetto XVI. He also works with classical subjects, and has frequently returned to Greek myth and especially Homer’s Odyssey, interweaving these classical stories and images with the evocative landscapes of his home in the mountains. The Murer family directs the Museo Murer in Falcade, which was built to house a large collection of works by Augusto Murer.

Franco Murer (b. 1952) is a painter and sculptor, who lives and works in his birthplace of Falcade in the Italian Dolomites. Growing up, he learned sculpture and painting alongside his father, the artist Augusto Murer, before studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice, from which he graduated in 1974. His vast oeuvre includes drawing, painting, and sculptures in different media, including wood and bronze. Much of his work centres on Christian subjects, and examples of his sculptures can be seen in the Vatican – such as his monumental fountain decorated with scenes from the life of St Joseph, dedicated to Pope Benedetto XVI. He also works with classical subjects, and has frequently returned to Greek myth and especially Homer’s Odyssey, interweaving these classical stories and images with the evocative landscapes of his home in the mountains. The Murer family directs the Museo Murer in Falcade, which was built to house a large collection of works by Augusto Murer.

This interview with Jessica Hughes was recorded on 1st November 2020. All photographs are reproduced with the kind permission of Franco and Nadia Murer.

A PDF file of this conversation is available for download.

Jessica Hughes: Thank you very much for this interview, Maestro Murer. We’re going to be talking about your interactions with Greek and Roman antiquity, and how these interactions are materialised in your paintings and sculptures. May I start by asking when you first came into contact with classical antiquity? For instance, did ancient Greek and Latin literature form part of your school education?

Franco Murer: Yes, they taught us the ancient texts at school, and we also read them at art school and at the Academy. However, these were texts that were linked directly to the history of art – that is, to the various stages of ancient art, from the work of Phidias onwards. We read sections of texts like the Odyssey – not in their entirety, but rather in pieces – in fragments – in such a way as to then perhaps draw them, and interpret them ourselves.

Another place to start would be with the marvellous Greek poet, Constantine P. Cavafy, when he writes [in his poem Ithaka] “As you set out for Ithaka, / hope your road is a long one, / full of adventure, full of discovery”. Fundamentally, this is the meaning of life, and it’s also the meaning of the labour of making art.

JH: I know that the Odyssey and the journey have been central themes in your work throughout your career. Before we talk about that, though, I wonder if you also read Virgil at school? I’m asking this partly because of all the bucolic elements in your paintings.

Franco Murer, ‘Notte di San Giovanni’, 2008, oil painting on canvas, 160x120cm.

FM: Virgil is unavoidable, because you meet him in the Divine Comedy too. We did study the bucolic poems at school – but also after leaving school, since they are part of life. They represent the history of Italy, especially the work of peasants, and the history of working the earth.

JH: What role did classical art play in your artistic training? For example, did you use Greek sculptures as models when you were learning to sculpt?

FM: Yes, certainly – and I think that many people do, when they are young. Our roots are in Greece, both from the cultural point of view – architecture, literature, sculpture – but also in terms of the market, trade, and the great democracy of Perikles. The relationship between Perikles and Phidias is fundamental to the history of art. Phidias made the Parthenon with all its metopes, but unfortunately he had to pay for them as well, since to eliminate Perikles they threw Phidias in prison. You see this same relationship between power and art in the collaboration between Alexander the Great and his sculptor Lysippos. Lysippos nourished the myth of Alexander – they needed each other.

JH: Have you travelled in Greece?

FM: Yes, I know Greece well. We have lots of friends there, and we’ve done lots of exhibitions there, in Kalamata, as well as Lepanto, Volos, Kos, and Leros. Greece is a constant source of fascination for me. The Greek people are too – they are so generous and warm, and it’s always a pleasure to meet them. There’s this idea, whenever one goes to Greece, one is going to immediately find oneself in the centre of myth. But when you arrive at Patras in the boat, for a moment, you find yourself without a myth. And there’s a moment of confusion. But then you find it. You take the road towards Olympia, and its Museum, and inside there you find the work of Praxiteles, and the Nike of Paionios inside – these are strong emotions, and it’s hard not to be influenced by them.

Franco Murer drawing the Nike of Paionios in Olympia Museum.

Then in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens…there’s the whole world in there. Although it’s true that you have some of it in England! I saw the Parthenon marbles many years ago in London. They have copies in the new Acropolis museum, although they also have some original pieces there too. You can tell the difference between the copies and the originals, but nevertheless it’s important to see them there, in front of the Acropolis, in the place where they were ‘born’. It’s a very interesting museum.

JH: And what about your travels around Italy? Did you go to museums with your father, Augusto Murer?

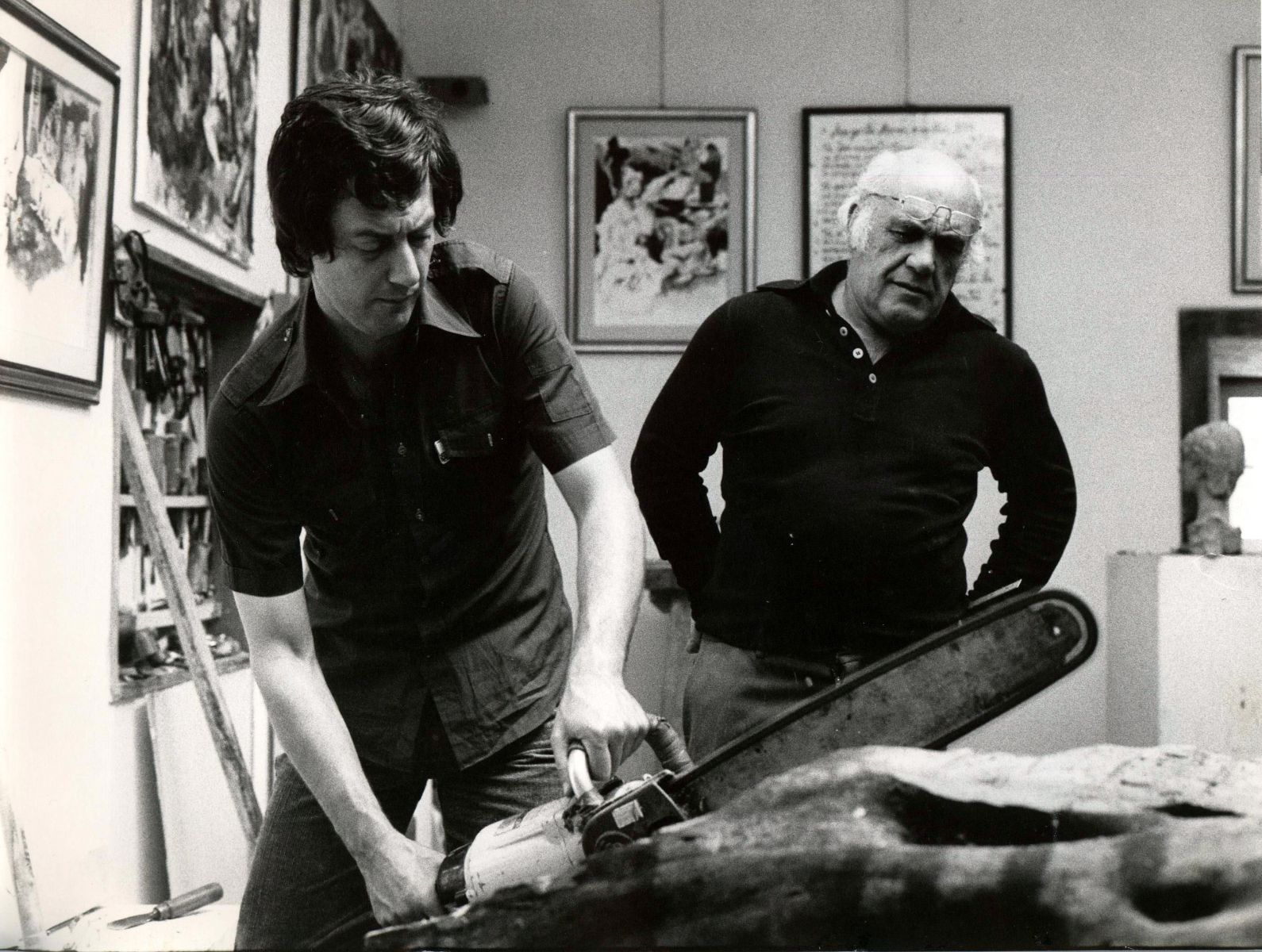

Franco and Augusto Murer in the studio in Falcade

FM: Yes, I went with my father. He also had a friend who was a painter and graphic artist, who loved Magna Graecia [Tono Zancanaro], and part of his work was linked to Selinunte. So when I was little, I heard those stories, and looked at these drawings. This nourishes your curiosity, and makes you want to go and find out where these things started.

JH: May I ask about your father’s perspective on classical antiquity? Where would we find traces of the classical past in the work of Augusto Murer?

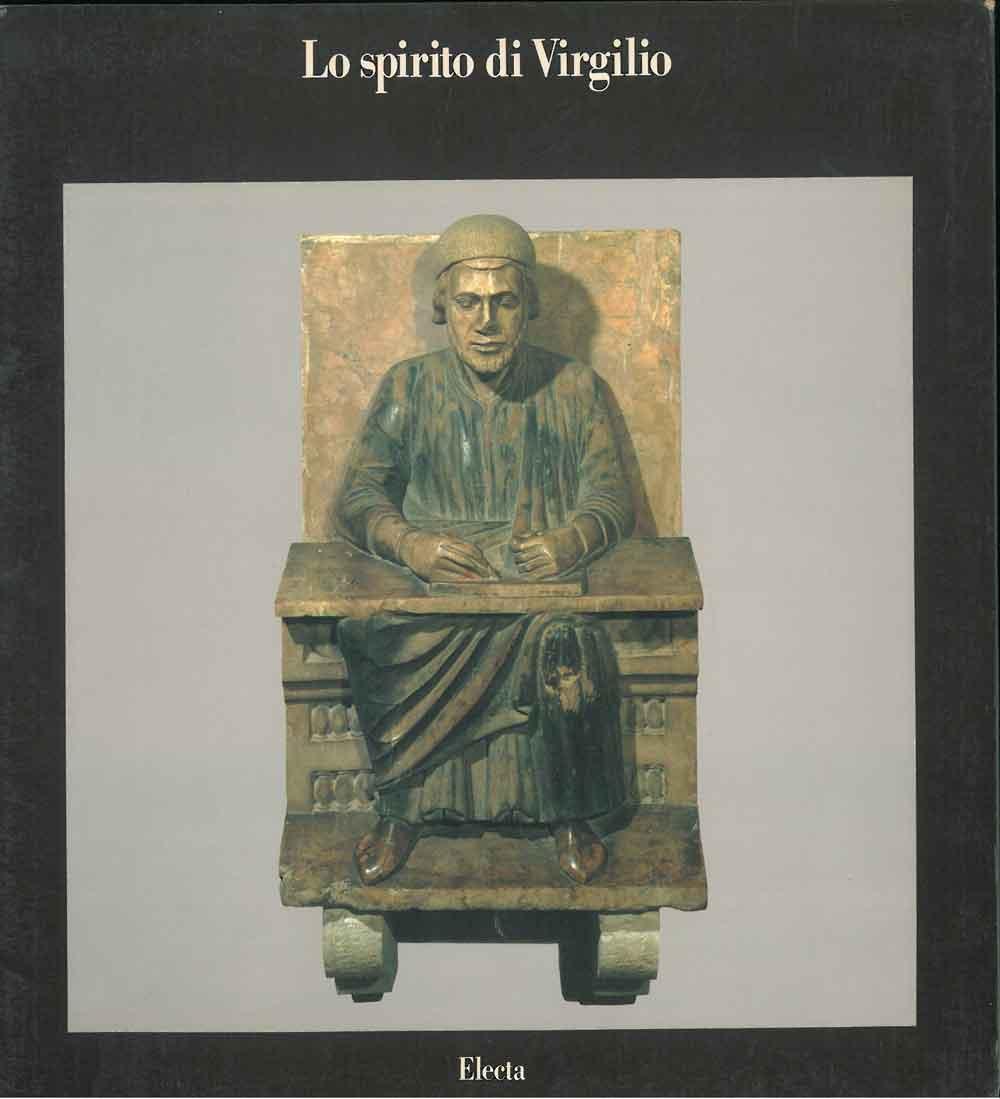

FM: He was, certainly. In fact, one important moment in his career was linked to Virgil – an exhibition that was staged in Mantova, on the occasion of Virgil’s Bimillenium in 1981. That show included works by eight European artists: Aldo Borgonzoni, Ruggiero Giorgi, Renato Guttuso, Giacomo Manzù, Henry Moore, Augusto Murer, Ernesto Treccani and Tono Zancanaro. There’s a catalogue of that exhibition, published by Electa, and it was inaugurated by Sandro Pertini, who was President of the Republic at that time.

‘Lo spirito di Virgilio. Otti maestri per un grande poeta.’ Catalogue of the exhibition held in Mantova in 1981

Franco Murer with Sandro Pertini (President of the Italian Republic) in Mantova, 1981

JH: Can you tell me about the work that your father contributed to that exhibition?

FM: He made some figures of Orpheus, and fauns and nymphs. Some were sculptures and some were drawings. They were able to include several of his works, because the exhibition was held in the [large] Palazzo Ducale in Mantova.

JH: Let’s turn to your own work now, and look at some examples. We’ve already alluded to the series with Odysseus/Ulysses and Penelope, so perhaps we can begin there.

How did this series of paintings come about, and how did you go about choosing which episodes and characters to depict?

Franco Murer, ‘Ulisse – Battaglia’, 2004, mixed technique: tempera and ink, 70x50cm

Franco Murer, ‘Ulisse’, mixed technique: tempera and ink, 77 x 55.5cm

FM: This was a graphic idea that I wanted to render freely, without being too tied to the Homeric text. The main idea is that of a journey, because, at the heart of it, that is really what life is about. It takes us back to the poem of Cavafy – where the adventure, the journey, and knowledge are all fundamental. I wanted to liberally interpret the idea of the Odyssey, but without being too specific, without there being a one-to-one relationship between the passages and the images. It’s a free fantasy, suggested by the text. You read the text, you interpret it, and you leave yourself free to dream a little, as well. That’s the scope of life.

JH: And it’s what keeps these myths alive. We don’t just read these ancient stories – we reinterpret them for our own times.

FM: They are always current. For example, this need that people have to travel, to meet, to be together – we’re seeing this right now, in this difficult period, when the lockdowns are causing psychological problems for many people. The physical distancing doesn’t help, either. You then understand that the need for the journey, and for the encounter, is fundamentally important for humans. We’re not born to be apart. We’re born to be part of a community.

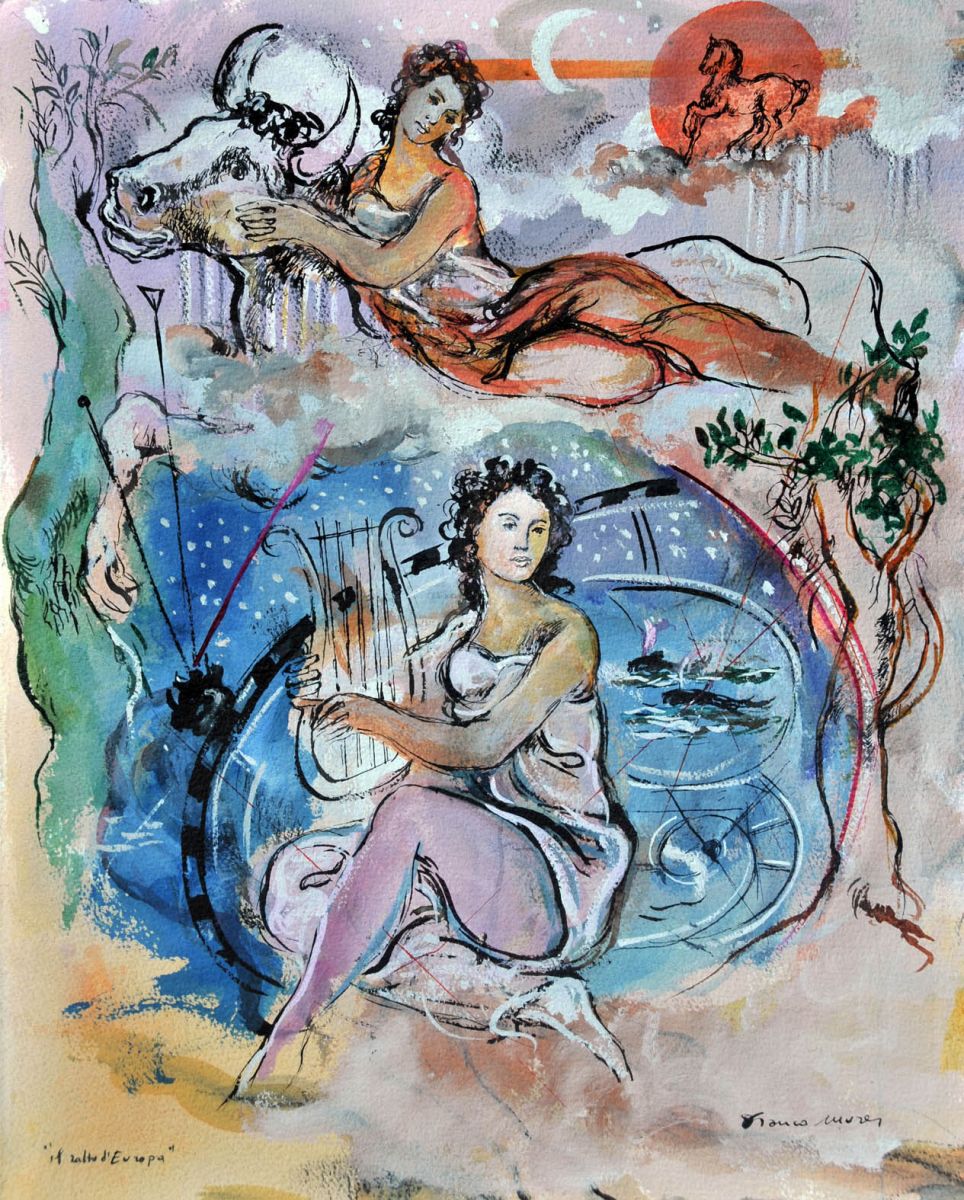

JH: Speaking of community, you’ve worked with the myth and idea of Europa as well.

Franco Murer, ‘Europa’, 2020, drawing in mixed technique, 40x50cm

Franco Murer, ‘Il Ratto di Europa’, 2014. Bronze, 53x68x30cm

FM: Yes, I’ve done paintings and sculptures of Europa. With that myth, you go right to the origins of Greek culture, and the meeting of humans and gods. Again, the most central part of the myth is about exchange. On Crete, there was trade – ships which exchanged goods like oil, amphorae, and products of the earth. And along with those goods, knowledge was exchanged too. That led to links with Sicily, and further north in Italy, and from there, with the rest of Europe. One painting of Europa that I did in 2013 is going now into an exhibition on Alexander the Great. The exhibition was meant to happen in September, but unfortunately Covid meant that it had to be postponed. Anyway, I’m preparing a series of paintings of Alexander the Great, each three metres high, but we’re also including paintings that are linked to the two-hundred year anniversary of Greek independence from the Turkish. The Europa painting will be in that exhibition, as a reference to Greece’s origins.

Franco Murer, ‘Alessandro Magno’, 2018-19, oil painting on canvas, 360x170cm

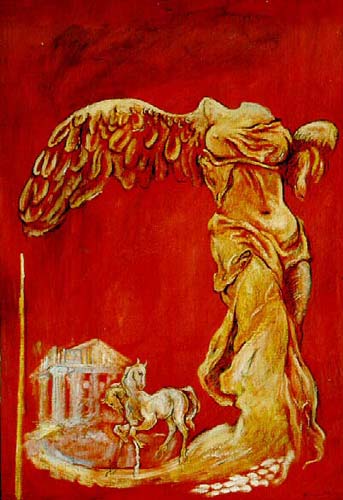

JH: Another figure from Greek art who appears often in your paintings is the image of the winged Nike of Samothrace – could you tell me about that?

FM: A few years ago, I made a series of works around a particular theme, called ‘Il mio paesaggio’ (‘My landscape’). This was a conversation that I needed to have with myself, in a complicated moment in my life. It was an autobiographical series. And it was inevitable that the Nike of Samothrace was part of that, because she was part of my studies, and my reading. When I was twenty years old, I went to the Louvre, and I saw the Nike at the top of the stairs. You can’t fail to be struck by that. I was especially fascinated by the huge wing! That day, I had planned to go and see a painting by Seurat, but I got lost in the Nike, and then in Gericho’s painting The Raft of the Medusa. When you’re young, you start off with one idea, but you fall in love with others along the way.

Franco Murer, ‘Il mio paesaggio – Nike', oil painting on canvas, 70x100cm

That’s why I went back to the Nike in this series of exhibitions I did, where I was speaking about my landscape, and my memories of childhood, like being in the studio of my father. When I was five or six years old, I used to leave the house in the morning to go to school, and I went past my father’s studio. There I would find tree trunks (at that time he was working with wood), sculpted into the figures of women, and of maternity and other subjects. That was my forest. Then I’d go out of the house (living on the mountain, we had a forest right outside), where I would meet ‘real’ bodies. But my true forest was the one from earlier – the one made by my father. This why I have a slightly distorted vision of what nature is like! I inserted the Nike into these scenes, which are both nostalgic and fantastic. She’s part of my internal landscape.

Franco Murer, ‘S. Michele protettore della Nuova Pompei’, mixed technique, 100x70cm

JH: Another winged figure that appears in your work is that of St Michael – for instance, you did a painting of ‘San Michele, Protettore della Nuova Pompei’ [St Michael, Protector of the New Pompeii], which is now on display in the Casa dei Pellegrini [Pilgrims’ Hostel] in the modern town of Pompeii. I would love to know more about this scene – particularly the juxtaposition of the classical and Christian elements.

FM: That painting came about because there was a gallery owner in Milan, who was originally from Naples (or perhaps even Pompeii). Some of her contacts were putting on an exhibition in Pompeii, and she asked me for a work with a link to San Michele and the Basilica [of the Blessed Virgin of the Rosary – of which St Michael is Protector].

But apart from that, I’ve done other St Michael images for the Vatican. I took part in a concorso [contest] for the fountain dedicated to Benedetto XVI, which I won, and so I made that. Then there was another concorso, and I made another St Michael, which I gave it to Cardinal Lajolo, who then in turn gave it to the Vatican, and a short while ago I received the letter which informed me it has been put on display in the Vatican Museums. St Michael is an extraordinary figure, and he is also linked to classical Greek ideas like the Nike of Samathrace, the work of Lysippos, the idea of this warrior, this man who represents the force of nature, but with the mystery of the wings, which are like those of Nike.

Franco Murer, sculpture in bronze of St Michael Archangel, 2011, 79x44x38cm, Vatican Museums

JH: The St Michael from Pompeii does seem particularly classical in style – the body, the pose, the drapery, the laurel crown he wears – even the background colour seems to evoke the red of the wall paintings at ancient Pompeii, which is just down the road from the Basilica.

FM: Yes, I wanted to do a classical figure. This idea, this thread, it always remains. And how could you not be influenced by the paintings of Pompeii – those extraordinary colours and compositions? I wanted to insert the Pompeian red into the scene, and to juxtapose the sacred element with the Pompeii of the excavations, to counter and compare the two things.

JH: In some ways, this painting could be a kind of symbol for your entire oeuvre, because you are constantly intertwining this thread of classical art with Christianity and the sacred. And the two things are mixed together to create something new.

FM: Well, if we go and read Greek mythology, we find lots of things that Christianity ‘recuperated’. At the beginning, at least, Christianity was practically superimposed on the pagan past. They are two different things, Christianity and paganism, but there are still similarities and parallels between them.

JH: May I ask what are you working on the moment, apart from the large-scale Alexander paintings? I can see a painting of a hermaphrodite in the background in your studio.

Franco Murer, ‘Il Viaggio’, oil on canvas, 90x160cm

FM: This hermaphrodite appears in a lot of my work, because of its dominant sense of classicism, clean and pure form, it’s so elegant. It’s emotional. It’s a statue that you find in the Archaeological Museum of Athens, and it really is extraordinary. There’s a Roman copy in the Capitoline museums, and also one by Canova. This shows that there is a link that continues. The whole work of Canova is…well, everyone departs from the Parthenon, the Belvedere torso. These are fundamental works. You can’t not know them, and you can’t compete with them either.

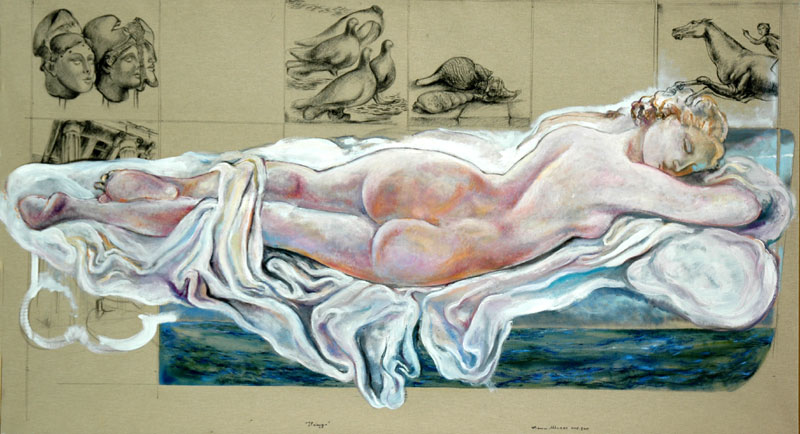

Franco Murer, 'Il tempo del mito e della memoria', 1994, mixed technique, 40x50cm

JH: As a final question, I wondered if you might say something about the magical and bucolic aspects of your work. There are many paintings that we haven’t yet discussed, of nymphs, and wooded landscapes, and mythological figures of the mountains. Do these also belong to the emotional and nostalgic ‘interior landscape’ that we talked about earlier? How much do you draw on that extraordinary ‘external’ landscape that you live in, in the Dolomite mountains?

FM: I am indeed inspired by the landscape, and by a love for the earth. In 1982, I put on a exhibition in Palazzo dei Diamante in Ferrara, which had the title L’Uomo e L’Ambiente [Humans and the Environment]. Already at that point in time there were starting to be some complicated situations around the environment – petroleum, shipping, and so forth. I did something a bit different there, although it was still connected to my territory – I used trees, and small dolls abandoned along the side of the street. Where I live, the natural landscape is unavoidable.

JH: And its conservation is getting more important.

FM: Yes, let’s say that we’re a little bit late with that.

JH: Maestro Franco Murer, thank you very much.

Find out more…

Website of the Museo Murer.

Biography of Augusto Murer.

Works by Tono Zancanaro.

Interview translated from Italian by Jessica Hughes.