You are here

- Home

- Isolation but “not on Earth”

Isolation but “not on Earth”

We are all in self-isolation. However, I suddenly realized that this new lifestyle that we all have acquired looks a bit familiar to me. I reminded myself that I have already spent five months in isolation (without even talking to my mum – for me, this is an extreme condition!). This isolation was "not on Earth, but Mars!"  I became part of a long-term Mars simulation mission in a desert and on an inhabited island. So, I thought I should share some of my experiences, challenges, and growth along this journey.

I became part of a long-term Mars simulation mission in a desert and on an inhabited island. So, I thought I should share some of my experiences, challenges, and growth along this journey.

How it all started

The story begins in 2016 when I was a master's student at the University of Essex. I was almost near graduation, and one morning, I received an email from Dr Shannon Rupert (Director of Mars Desert Research Station (MDRS)):

“Hi, Anushree -- I would like to talk with you about some opportunities for you at MDRS. Particularly we would like to have you join the Mars 160 team… Right now we have you scheduled as part of a crew in Jan 2017, but we really feel you would be a wonderful addition to the Mars 160 project, so we are hoping to find you a place with us there. Your proposed research is aligned with what we will be doing on Mars160” (I still have this email starred  ).

).

Honestly, I could not believe it and my joy knew no boundaries. But it was all not that simple.

Of course, I said yes. But after that, I never heard back from Shannon. I thought perhaps she forgot or found some other suitable candidate. I followed back but no reply, and for me, that was enough to believe that perhaps this was not meant to be. After about 20 days of waiting hopelessly, I directly received a WebEx meeting invite from Shannon – it was a meeting for the Mars160 crew and mission planning. I smiled. But that was not it. There came a point when it seemed impossible for me to join the mission because my US visa application went into some additional processing. I was told that it is like a black hole and no one can tell when you get your passport back. The mission was going to start in a week, and I did not have my passport. I cried a lot. Also, my Canadian visa (for the Arctic program) got rejected for an unfair reason even after waiting for 3 months. So, several layers were added to the story before the actual story even started. But it happened, eventually!

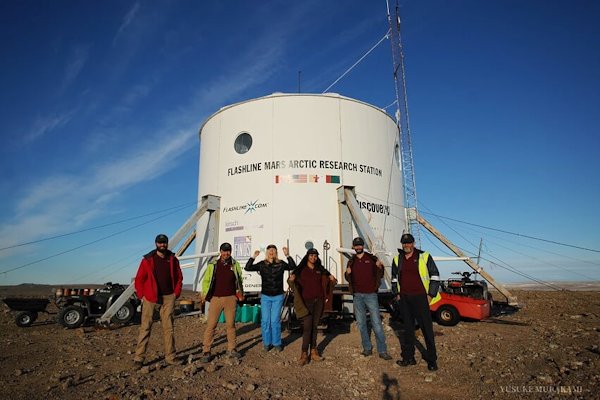

It was a Mars160 Twin Desert-Arctic Analog Mission organized by The Mars Society (TMS). All MDRS rotations are 2-weeks in duration where students, engineers, scientists, medics, and even journalists carry out rigorous field studies and human factor research under the constraints of a simulated Mars mission. But for the very first time, TMS planned a 160-day twin simulation mission – 80 days at MDRS (near Hanksville, Utah desert) and another 80 days at Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station (FMARS on Devon Island in the High Arctic). Also, I was appointed to stay at MDRS for another two weeks as an Executive Officer and Crew Biologist of the Crew 172. The crew of 7 involved members from France, Canada, the United States, Russia, Japan, Australian, and India.

For me, it all started off being a small volunteer of TMS. I joined the MDRS Mission Support team as a CapCom (Capsule Communication) in 2014 and became part of this idea of Mars exploration for the first time. Being CapCom was extremely fulfilling – I was responsible for making sure the crew’s safety and wellbeing, and smooth mission operation. I thought this could be my small but important contribution towards the idea of how a human exploration of Mars would be like. Based in the UK, this would require me to be up in the night from 2 to 4 am to be able to match the mission operation timings in the US for an entire week shift. Shannon was constantly monitoring my work. At that time, I had no idea what I will end up with – the Mars160 mission.

So, while I was CapCom, several members of the TMS Mission Support team started encouraging me to join the on-site crew. But I was not interested as I thought maybe this was not the right time for me. But I applied for a 15-days rotation (reluctantly) even though the deadline was passed, but since I was a volunteer, I had this leeway to apply. I just took a chance but somewhere believing that I am not going to do that. Another side story is that when I opened TMS website to get more information about the application procedure, I saw this headline that TMS is organizing an unprecedented long-term Mars simulation mission, and there was a crew of 7 already appointed. That moment I told myself – okay, there is no place for me here and I should try this short-term program. I put together a proposal, applied, and forgot about it.

Shannon probably came across my application and she was looking for a Crew Biologist for Mars160. So, one morning I woke up with Shannon’s email that I have mentioned above. Even though I had no idea what it is going to be like, I jumped to the opportunity. Much later I came across these words of Richard Branson - “If someone offers you an amazing opportunity and you’re not sure you can do it, say yes, then learn how to do it later” – I realized that I had done it already!

MDRS campus

FMARS: when we arrived! Posing in our mission t-shirts! Anastasia(the girl behind me) forgot hers

Living in isolation

We were a crew of seven, locked inside a cylindrical can that we call our Mars habitat. We would only go out of the habitat either for fieldwork or any maintenance-related task wearing a spacesuit – we call it extravehicular activities (EVAs). These spacesuits weigh approximately 15 kilograms with the weight of an oxygenator on our back (to provide our air to breathe), helmet, boots, sampling tools, and any extra baggage or gadget needed for the fieldwork.

As part of the simulation-isolation protocol, we could only have asynchronous textual communication (a time delay of around 30 minutes in receiving and sending responses). We would take shower once in a week (but we did have our other options!) because we needed to save water that we would not be provided very frequently. We were not allowed to interact with any other humans in person (except seven of us). In case we encounter other Earthlings (some super curious tourists do trespass MDRS campus), we would pretend like we do not see anyone. We would feel bad about it because they would wave, and we were not allowed to react. We would not have any fresh food, but only dehydrated food that we would rehydrate before eating (dehydrated ice-cream was cool, though!). I give huge credit to my time at MDRS and FMARS for my love of chilies – the food used to be so bland. The only fresh stuff we used to have that we would grow inside our habitat (lettuce and herbs) in our smart pots that would simulate the sunlight. The simulation taught us how to play with scarcity.

Especially, living on an isolated uninhabited island in the Arctic took us to another level of extremeness. People might not want to know the details of our day to day routine, but some things are worth mentioning. Since we had lost half of the food items we were supposed to receive (it never arrived) we managed with some old dehydrated Indian food that previous expeditions did not use.

We would have to fetch water from a fresh-water stream. It used to be freezing cold inside the habitat but since we had to save the fuel, we would turn on the generator only for a certain amount of time in a day. Since it was summertime in the Arctic circle, we would have 24 hours of sunlight. So, to maintain our normal sleeping hour we would put circular wooden planks on all the portholes of the habitat to block the sunlight at a fixed time in the “night”. The Arctic was not as vibrant as the desert in Utah – it was grey and gloomy. Any transportation from the civilization to that island relies upon a small Twin Otter aircraft, which is entirely weather dependant. So, in case of any injury or scarcity of food, we would have to wait for the aircraft to come and save us.

Strawberry and tomato plant growing in the Smart Pot simulating the sunlight.

Japanese space food (left above) that only needs boiling water. Russian space desert: cottage cheese with black currant puree.

Our MDRS sleeping quarters

Our communal computer to contact the outer world based in the Arctic. It’s tiny, I know

Our communal computer to contact the outer world based in the Arctic. It’s tiny, I know  and it has a French keyboard!

and it has a French keyboard!

Why? do we look so serious?! It is chocolate pudding on the table (MDRS).

A birthday celebration at MDRS.

When the mission ended and we all came out of the simulation, I first called up my parents. It was overwhelming. My mum started crying on the phone when she heard my voice. For me, the most challenging part of this isolation experiment was not being able to interact with the family. Living in an isolated environment with people from different cultures altogether and doing physically demanding EVAs, I put myself in precarious conditions a lot of time. However, it was not as hard as not being able to tell my mum simply what I did in a day, what did I eat, and things like that. But I survived! Also, I remember I felt taken aback seeing roads and cars and a lot of humans

Some of my thoughts on living in confinement that I jotted down based at MDRS:

Sol (day) 80: [December 13, 2016]

“Being part of a long-term Mars simulation mission and living in an isolated condition is not easy. You tend to feel monotony sometimes or want to stay confined in your own world. But then your WORK reminds you of the love you kept harbouring in your heart, and you crossed all the boundaries to chase it, to achieve it. I think, to not to lose the perspective is the biggest challenge of a long-term simulation. The most wonderful thing I found about our sojourn at MDRS is – we lived and grew beautifully. It sounds idealistic, but we have done it.”

I wrote another report (below) on day 92 based at MDRS. I had mixed feelings when I was writing this which stemmed from the fact that I was somehow getting face to face with the volatility of the world we were living in.

Sol 92: [January 14, 2017]

“You are on Mars.

When you are on Mars, life is unpredictable (exactly like it is on Earth, but on Mars, it is a little bit more). I have always written about the beauty of this place; how those small portholes of our Martian cylindrical home let us gaze the surreal red backdrop and make us immerse into our own sense of awe and appreciation. How our home stands tall against all the oddities of Mars. Living in this place, sometimes you feel that you are getting interviewed by your own sensibilities… It gives you a space to emerge beyond you. That is true. Even inside the small habitat, it gives you a wide space. I mean, wide space inside the very YOU. You learn to stabilize your emotional fluctuations by inevitably diving into the situational intricacies. It is a subtle process. And on Mars, you love being in this process, because you can see, that you are growing.

But, while witnessing all these nuances of living on Mars, something else dawns on to you. You come to know that Mars limits your extensions in so many ways. These limitations are accompanied by the fact that “it’s Mars, not Earth”. You feel helpless in absence of required supplies, breakdown of a system, inconsistencies in the communications and coordination with the team based on Earth, merciless weather preventing you from exploration, and many more. As I said because it is Mars, not Earth. It will pose its extremeness on you in some way or the others. We do have similar limitations on Earth, but those may not be fixed as swiftly, as feasibly on Mars as on Earth, or perhaps, they could not be fixed ever. Encountering these limitations is also part of this process of humans going beyond the human frailties. You rise. This transition is important. When you are on Mars, it may not be picture-perfect. And, when it is not, you must live with it. So, when you have all these lemons, you surely learn to make good lemonade. I remember what Shannon said once, ‘This is the whole idea actually’”.

I think my isolation “off-Earth” has a lot to do to my isolation on Earth – it taught me about patience and making the best out of the given situation. This mission was my first opportunity to work with such a diverse group of people in a not-so-natural environment. We all had our own minds and our own ways of living life. But when we came together, we gradually learned to be more accepting and unconditional towards one another. I think it is because we came together for a cause. And, that is what inspired the sense of unity we had. It all seems so relevant in today’s time. I think it is also important sometimes to contain yourself and go within. Isolation can be an opportunity, perhaps to explore the unexplored dimensions of yourself. That is what this isolation experiment did to me. Now, I look back and only smile.

Twin Otter that transported us to FMARS.

When we finished the Arctic chapter!

I was nominated for British Council’s UK Alumni Award (2018) for taking part in the mission right after receiving my master's degree from the UK

Author:

Anushree Srivastava

is a PhD student in the School of

Environment, Earth and Ecosystem Sciences

at the Open University