You are here

- Home

- Blog

- Embracing ‘Virtual Insanity’: Exploring the use of a virtual reality courtroom in legal education

Embracing ‘Virtual Insanity’: Exploring the use of a virtual reality courtroom in legal education

Virtual reality (VR) refers to a technology that creates a three-dimensional computer simulated environment that can be experienced through a headset or with a computer using a monitor, keyboard, or mouse (Carkiroglu et al, 2019). This simulated environment is designed to replicate real-life settings such as in our case a virtual courtroom. VR technology uses computer-generated graphics and sounds to create a sense of immersion within the environment (Dede, 2017). It facilitates the user to walk around in the space and interact with objects and simulated computer-generated people-avatars. The immersive and interactive aspects of VR offer considerable potential for use in higher education particularly as it can facilitate forms of experiential learning-learning by doing (Jacobson, 2017).

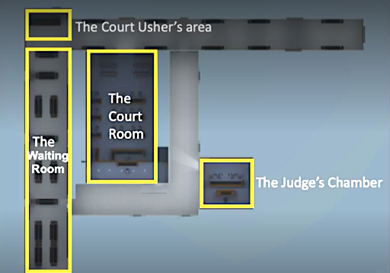

In 2021, academics from the Open University (OU) Law School started a project to develop a virtual courtroom (VCR). The aim was to create an immersive virtual environment that gave students a realistic experience of a modern courtroom within which they could interact with other students. The purpose of the courtroom is for students to come together to collaborate and undertake courtroom advocacy. The VCR has elements of both simulator and game systems. It follows a typical multiplayer first-person shooter game (FPS) design with 3D graphics, multiplayer interaction, and audio communication between users. It was designed in Unity which allows for the creation and operation of interactive 3D content, unlike full immersion VR it uses augmented reality through a virtual interface.

There are several possibilities for the VCR beyond an educational setting. A VCR has the potential to support free advice organisations and litigants in person with preparation for court hearings. It could also be used to facilitate training for legal professionals and other professionals such as the police and social workers. In legal education we teach students about courts and legal proceedings, through interacting within the VCR students can learn about the layout and functions of courtrooms. The VCR can also facilitate courtroom advocacy often referred to as mooting. Mooting is a simulation of a court hearing, often an appeal in which law students represent one of the parties in a hearing and argue the case before a judge. It focuses on arguing points of law rather than engaging in a mock trial. It is conducted formally following legal rules and procedures and gives law students the opportunity to develop and demonstrate their advocacy skills. Mooting is a useful educational tool for law students as it supports the development of confidence, legal research, writing skills and persuasive advocacy.

Mooting is a common feature in legal education with many universities having invested in purpose built physical moot courtrooms. As a distance learning university, we wanted our students to have access to a virtual moot courtroom which has become increasingly more important as court hearings have moved online since the COVID-19 pandemic when courtrooms closed. Virtual courtrooms use technology to conduct legal proceedings remotely. The VCR replicates many aspects of virtual hearings: it allows participants to connect and communicate from different locations using their computers and can be conducted in real-time. It also reflects some of the challenges associated with virtual hearings such as technical difficulties, reliability of technology and the participants having the skills to navigate and participate effectively online.

We conducted a small-scale project to test the VCR with students. We invited six students to participate in a moot within the VCR. Some of the students had previously mooted and some were novice mooters. The purpose of the research was to find out how realistic the VCR was and although we could not replicate a physical courtroom, we were interested to find out how the experience compared to virtual mooting in Zoom or Teams. The moot was the first time students had entered the VCR and that produced some interesting results for the research team.

Some students initially struggled to use their keyboard or mouse to navigate to the door of the courtroom through the waiting room and the corridor. Once they entered the courtroom there were some challenges in placing themselves in the advocate bench and making their avatar sit and stand. These are issues that we know can be resolved through giving students early access to the VCR and allowing them time to practice and orient themselves in the environment.

Carkiroglu et al (2019) argue that it is important that users consider the virtual environment as realistic and authentic. Students commented on the realness of the environment and how it was interactive and engaging. Student A said that:

Visually seeing people did help a little bit. It made it feel like you were sitting there together doing it. It felt like you were in the room. You heard background noises, even walking to the courtroom, that I felt was really great.

Students also suggested the VCR brought benefits over the use of Zoom or Teams, they commented that the VCR felt more formal and gave it a level of seriousness. Student B said that:

It was much more engaging than doing a general Zoom or Teams chat. You could get into the spirit of things. And, also being able to customise your own avatar is always nice. It gives that slightly personal touch.

This was a small-scale research project which has produced valuable insights into the VCR. We are continuing to test the VCR to explore how other types of users interact with the platform and we are hoping to develop the prototype further. We are excited about its potential and the future possibilities.

References

- Çakiroğlu, Ü., & Gökoğlu, S. (2019). “A Design Model for Using Virtual Reality in Behavioral Skills Training.” Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57(7), 1723–1744. https://doi-org.libezproxy.open.ac.uk/10.1177/0735633119854030

- Dede, C., & Richards, J. (2017) “Strategic planning for R & D on immersive learning”. In Virtual, augmented and mixed realities in education, D. Liu, C. Dede, R. Huang & J. Richards (Eds.), pp 237-244, Singapore: Springer

- Jacobson, J (2017) “Authenticity in immersive design for education: Where is the pedagogy?” In Virtual, augmented and mixed realities in education, D. Liu, C. Dede, R. Huang & J. Richards (Eds.), pp 237-244, Singapore: Springer

Francine Ryan, Open Justice Centre Director and Senior Lecturer in Law

Francine is a qualified solicitor, Senior Lecturer in Law and Director of the Open Justice Centre at The Open University. Francine has worked to develop a range of innovative and technology-enhanced opportunities for OU law students including the Open Justice Online Law Clinic. Francine’s research areas are in technology and the law.

Jon-Paul Knight, Open Justice Centre Manager

Jon-Paul is the manager of the Open Justice Centre and most recently worked as a Qualification Manager in Law and Business. He is responsible for coordinating the work of Open Justice, and supports the work of the Law Clinic and the Public Understanding of Law activities.

Blog posts

- What happens when apprentices are made redundant 16th January 2024

- What is most important when integrating ‘green skills’ and sustainability topics into learning and teaching strategies? 11th December 2023

- Understanding what practice tutors in the Faculty of Business and Law need and want in their induction 6th December 2023