Worksheet

Click on the image for a larger view.

Specimen answers/discussion

- The letter has noted press reports about a freeze on the recruitment of women police. An earlier response from New Scotland Yard (D. Peto was Dorothy Peto who had served as a woman patrol in the First World War, and then in the Birmingham Police before joining the Met in 1930) had told her not to believe everything reported in the newspapers but that the reports had some truth. Edith Tancred goes on to complain that there are insufficient women police for the tasks expected of them, and that this was in spite of repeated promises to increase their numbers.

The module pointed out that women police officers were not seen as involved in 'proper' police work by many (and this was especially the case among some of their male colleagues and male superiors). Following the Geddes Axe ten years earlier, the future of women police had seemed in doubt. From your general knowledge of history you may have noted that this letter was written at the beginning of the 1930s – a decade noted for its economic difficulties. No wonder there were concerns that women officers would be the first to have restrictions on their recruitment. - The tasks of women officers during the inter-war period (and indeed for a generation after the Second World War) were largely restricted to dealing with women and children. In this they were being required to pursue a gendered role – an obviously maternal one as far as children were concerned. It was for this reason that male officers and others dismissed their tasks as not 'proper' police work. But this was not an issue confined to the police. The notions of separate male and female spheres had become particularly sharply drawn during the Victorian period and had been reinforced with medical assumptions about the biological and mental fragility of women. These ideas remained prevalent well into the twentieth century.

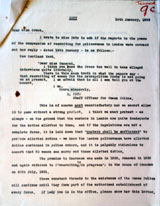

WPC 18 Ellis and Inspector Clayden patrolling outside Bow Street Police Station, 1924.

WPC 18 Ellis and Inspector Clayden patrolling outside Bow Street Police Station, 1924.