by Emma Bridges

A common thread running through the research and teaching of many of us who work in the department of Classical Studies at the OU is the study of classical reception – that is to say that we think about the ways in which, and the reasons why, ancient Greek and Roman ideas, texts and material culture have been revisited and refigured by later cultures and societies.

One of the most challenging aspects of thinking about classical reception is also, for me, one of the most exciting. In order to develop an understanding of the ways in which themes and ideas have been adopted and adapted in new contexts, a researcher must frequently step outside her own comfort zone, looking beyond the texts with which she is most familiar and exploring a range of genres, historical periods and geographical settings. Following the journey of a theme across time and space can yield fascinating and sometimes unexpected results, and the researcher who does so often needs to become familiar with areas of study of which she had little prior knowledge.

My recent book, Imagining Xerxes, took me on one such journey; in tracing the ancient cultural responses to the figure of the Persian king whose invasion of Greece was famously defeated against seemingly overwhelming odds, I found myself examining ancient sources which spanned a period of around 700 years, with a geographical spread incorporating Greece, the Roman empire and ancient Persia itself, and in a vast – and sometimes daunting – array of diverse literary genres.

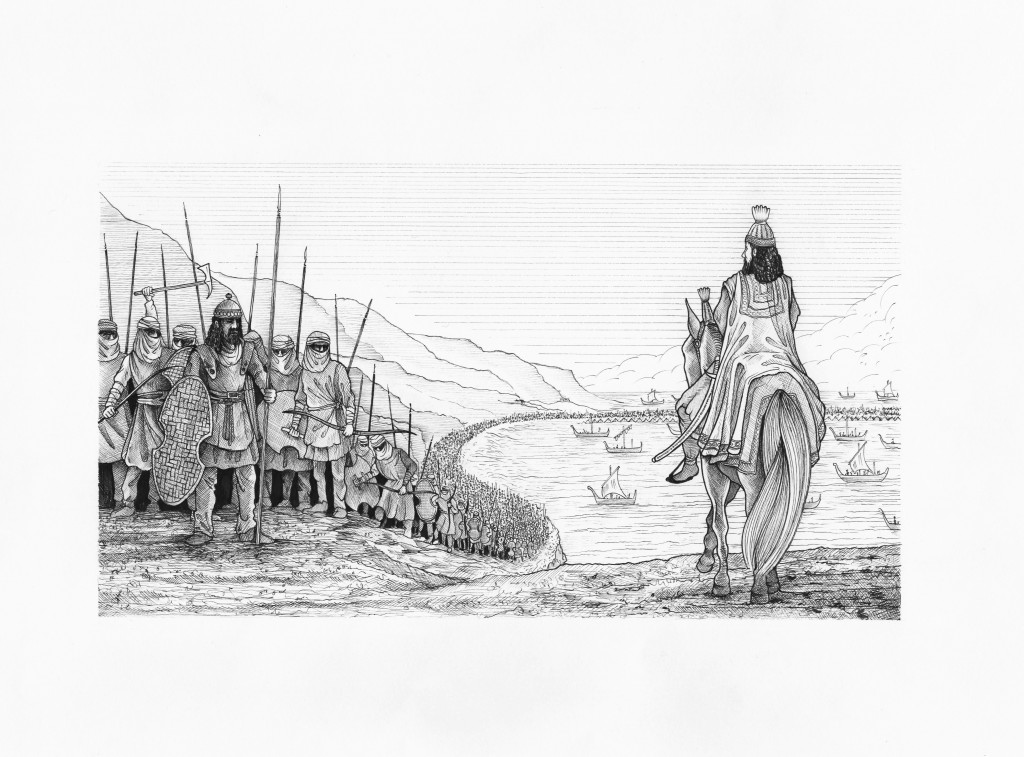

Xerxes crosses the Hellespont.

Original illustration from Imagining Xerxes (2014). Image copyright Asa Taulbut. Reproduced by permission of the artist.

As a scholar, I have always felt most at home with the Greek texts which were written in the fifth century BC – thus, when I started out, I knew a fair bit about Aeschylus’ Persians, in which a defeated Xerxes appeared on the Athenian tragic stage, and about Herodotus’ historiographical account of the course of the Persian Wars. In the course of my research, however, I also needed to tackle sources ranging from the inscriptions and relief sculptures of the royal palace complex at Persepolis, to biblical texts (Xerxes appears – named as Ahasuerus – as a key figure in the Book of Esther), to Roman and rhetoric and satirical poetry. Along the way I would discover that the historical figure of Xerxes was reimagined and reshaped in astonishingly diverse cultural settings, and that portrayals of his character – shaped by the historical circumstances in which they were produced as well as by the literary agendas of the authors who wrote of him – ranged from images of him as the archetypal and destructive enslaving aggressor, to a figure synonymous with the luxury and exoticism of the Persian court, or as an example of the vacillations of human fortune.

The joy of this kind of work is that there is always more to discover; every text or artefact encountered, every ‘reception’ of an ancient work or idea, has a context – literary, artistic, intellectual, historical – which needs to be investigated and explained if we are to understand why themes from the ancient world recur where and when they do. That’s good news for people like me, who love the challenge of getting to grips with something new!