This week Elton Barker, Reader in Classical Studies at the OU, tells us about his recent trip to the University of Iowa for the ‘Linking the Big Ancient Mediterranean’ (#BAM2016) conference.

With this month’s news in the UK being dominated by the EU referendum and specifically the issue of migration, a fortnight ago I was making good my escape, so I thought, to the relative sanctuary of the American Mid-West. But, in addition to being detained upon entry to the US at Chicago O’Hare airport (the inconvenience of a missed flight a merest hint of the difficulty many experience when travelling), participants at the conference to which I had been invited time and again came back to a matrix of contemporary concerns, relating to ideas of networks and mobility; standards, services and accessibility; and transformation.

With this month’s news in the UK being dominated by the EU referendum and specifically the issue of migration, a fortnight ago I was making good my escape, so I thought, to the relative sanctuary of the American Mid-West. But, in addition to being detained upon entry to the US at Chicago O’Hare airport (the inconvenience of a missed flight a merest hint of the difficulty many experience when travelling), participants at the conference to which I had been invited time and again came back to a matrix of contemporary concerns, relating to ideas of networks and mobility; standards, services and accessibility; and transformation.

Perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised: the conference was entitled “Linking the Big Ancient Mediterranean” (BAM) after all, and came with the promise of “leveraging the ancient world’s impressive and growing body of linked data to provide an innovative platform for research and teaching”. Organised by our Iowa hosts Sarah Bond and Paul Dilley, #BAM2016 brought together an array of scholars and research developers to talk about not only what digital work they were undertaking but how and why that was important for understanding their topic. The work represented was highly diverse: language texts ranged from Greek, Latin and Persian (Open Philology; Digital Latin Library), to Coptic (Coptic Scriptorium) and Syriac (Syriaca.org); disciplines from epigraphy (Inscriptions of Israel/Palestine; http://www.trismegistos.org/) and papyrology (http://papyri.info/), to graffiti (Ancient Graffiti Project), numismatics (Nomisma.org) and archaeology (3-D modelling of cultural heritage sites); and approaches from focusing on linking places (Pelagios), to linking people (SNAP:DRGN) and time (PeriodO). There were also a number of useful resources presented, such as the Classical Language Toolkit and a gazetteer of ancient place names (Pleiades Project). (You can see the full line-up at the BAM conference website.)

Far from occluding the hard graft and uncertainty that goes into research, digital activity was shown to shine a light on scholarly practices. Nowhere was this better exemplified that in the project presented by Adam Rabinowitz, called PeriodO. Where a gazetteer like Pleiades has allowed researchers to agree on what place they are talking about (whether one uses the character string “Athens” or another “Athina” or even “Αθήνα”), which means that online documents referring to the same place can now be linked together (by Pelagios—the project I’m working on, more on which in a future post), there is no such agreement on time. Different scholars can—and frequently do—use the same period terms to mean widely different things, or with respect to widely different spaces. For example, how does a computer know that 323 BC, the Hellenistic period, the age of Alexander, etc. all specify more or less the same time? PeriodO, a Gazetteer of Period Definitions, is an attempt to bring some order to this category chaos. Thus, an element of scholarly publications so familiar as the expression of time was revealed to be hugely complex and complicated because of the attempt to apply it in a digital realm. The same is true too, as Ryan Horne (Technical Director at BAM and map guru at the Ancient World Mapping Center) pointed out, of maps—and visualisations more generally: how do you visualise uncertain or ambiguous data?

So, ambiguity and uncertainty were key take home messages—ironically, arguably, given how precise and certain digital data first appear. (We all need to be educated in reading visualisations and interpreting search results, not just our students.) But there are at least three further points to make about the projects presented:

1. Collaboration: as is clear from the brief narrative about PeriodO, it has built on previous and on-going work in the field, specifically by adapting an approach to connecting data taken from Pelagios’s focus on places; and Pelagios itself has been possible only because of Pleiades (among a whole host of other partners). There are various ways of doing collaboration of course: at Iowa, they have a dedicated in-house Digital Scholarship & Publishing Studio, which helps to support scholars and provide assistance in addressing critical issues such as preservation and sustainability (more longstanding problems that haven’t gone away now that we’ve moved to the digital realm). What #BAM2016 revealed, however, is that collaboration also takes the form of teams of scholars and research developers that cross not only institution but also continents. (Pelagios’s Commons Committee is formed of both groups from European, US and South American institutions. And such collaboration as being developed by PeriodO, Pelagios and others is at its basis a way of connecting data and facilitating further collaboration—an infrastructure from the ground up, as it were.

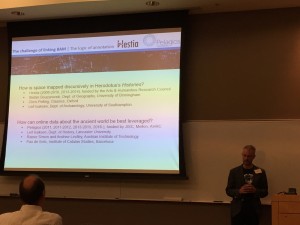

2. Openness: a common element of all the projects (including Iowa’s Walt Whitman archive), which underpins the collaborative practices noted above, is the fact that they are open and accessible to all. At the very least openness means being able to access data and material openly—so, for data providers/curators, this means not holding data behind a paywall or making them accessible only via institutional networks. An indication of openness is the use of permissive Creative Commons (CC) licenses, such as those recently advertised by the AWMC for maps or those used by Perseus, which are importantly for not only allowing use but also enabling re-use. (The Hestia project was able to “reuse” the Perseus text of Herodotus, to conduct various digital mapping experiments. I write more about this experience, in the context of digital texts more generally, with Melissa Terras.) In fact, sharing extends beyond data: a number of the projects are using the GitHub online repository to make their tools and code available, which can then be used and improved upon by the community.

3. Community: and so we get to the c-word—the human factor in the digital world. As part of their goal of openness, all the projects had in mind a public audience that includes but also somehow extends beyond academia. (How to address different audiences was a major concern highlighted by a number of speakers.) As part of their interest in collaboration, all the projects had in mind, too, building common methods and processes for working with digital data and tools. In fact, together with technical development, community building is the aim of Pelagios Commons, on the understanding that digital resources will remain a niche product and the preserve of the few unless they can be embedded in everyday practice. This is not only a question of how data can be produced but also how data can be consumed: while digital classics guru, Sebastian Heath, was presenting his work on Mapping Roman Amphitheaters, thoughts turned to how his combination of narrative and modelling approaches could form a recognisable scholarly publication. (Or, rather, how they currently don’t.) More challenging still: now that we are able to link between datasets of highly varied nature—texts, databases (of archaeological material), images (of maps, artefacts, etc.)—what happens then? How does one read archaeological excavation data alongside a literary text? And, even if one has as the target the Bigger Ancient Mediterranean picture, how can we put these diverse data together to make sense of this highly contested, rapidly changing, transforming space?

I’ll finish my summary on this note of caution about the possible transformative, even disruptive, effects of the digital on traditional scholarship, though other opinions are available. (See, for example, the excellent blog posts on #BAM2016 by Michael Satlow and Ryan Horne, while an archive of all the tweets—and there were many—has been created in storify.) But to end, paradoxically, I’d like to  briefly sketch how I began my presentation, with Herodotus. We are all by now familiar with the Greek – barbarian axis by which Herodotus introduces his inquiry into the Persian Wars, and which has proven influential for how space—at least the Mediterranean space—is still viewed as divided between West and East (or a European vs. Oriental/African other). We even hear an echo of Herodotus’s opening concerns just a few chapters into his narrative, when it is said that the Persians consider “Asia and the barbarian nations dwelling there” their own, while considering Europe and Greece (or, more accurately, the “Greek thing”, to Hellenikon) separate (1.4.4). Yet, that viewpoint is pointedly attributed to Persian wise men; observing how Herodotus begins his attempt to put together (sumballesthai—a word Herodotus uses to describe moments of interpretation) his Big Ancient Mediterranean suggests a far more complex and uncertain route. Immediately the category distinction between Greek and barbarian is complicated and compromised by the introduction of not only Persians but also Phoenicians (1.1: Are they both barbarian? To what extent? In the same way?) And not only do the Phoenicians enter the scene already networking (carrying Egyptian and Assyrian merchandise here and there and to Argos), but they have a different story of the origins of the conflict (1.5.2). The Mediterranean comes across as an already highly interconnected, diverse and contested space, and Herodotus’s way of putting that space together—to borrow a contemporary idea—highly networked. (For more on Herodotus’s networked thinking, see Hestia’s New Worlds OUP book.)

briefly sketch how I began my presentation, with Herodotus. We are all by now familiar with the Greek – barbarian axis by which Herodotus introduces his inquiry into the Persian Wars, and which has proven influential for how space—at least the Mediterranean space—is still viewed as divided between West and East (or a European vs. Oriental/African other). We even hear an echo of Herodotus’s opening concerns just a few chapters into his narrative, when it is said that the Persians consider “Asia and the barbarian nations dwelling there” their own, while considering Europe and Greece (or, more accurately, the “Greek thing”, to Hellenikon) separate (1.4.4). Yet, that viewpoint is pointedly attributed to Persian wise men; observing how Herodotus begins his attempt to put together (sumballesthai—a word Herodotus uses to describe moments of interpretation) his Big Ancient Mediterranean suggests a far more complex and uncertain route. Immediately the category distinction between Greek and barbarian is complicated and compromised by the introduction of not only Persians but also Phoenicians (1.1: Are they both barbarian? To what extent? In the same way?) And not only do the Phoenicians enter the scene already networking (carrying Egyptian and Assyrian merchandise here and there and to Argos), but they have a different story of the origins of the conflict (1.5.2). The Mediterranean comes across as an already highly interconnected, diverse and contested space, and Herodotus’s way of putting that space together—to borrow a contemporary idea—highly networked. (For more on Herodotus’s networked thinking, see Hestia’s New Worlds OUP book.)

Putting aside these opening skirmishes of accusation and counter-accusation, Herodotus asserts that he’ll investigate cites both small and large alike, since, he reckons, happiness does not reside “in the same place” (1.5.4)—a striking metaphor carried over from the spatial realm to the analysis of human life. For Herodotus, the Mediterranean was already a world in motion. In antiquity this insight anticipated Thucydides’s anatomisation of the great “movement”, kinesis, of his time, the war between the Athenians and Spartans. So it is again now, and we have an obligation as researchers to inquire into its causes and unpick as best we can the various threads that provide the dominant stories of our day.

Editor’s note: You can find Elton on Twitter @eltonteb