The First World War and Women Patrols

During the Edwardian era (1901-14) a great deal attention was paid to 'deviant' female sexual behaviour. Social surveys by Charles Booth and Joseph Rowntree pointed out the vast numbers of people living in poverty in, respectively, London and York. Fears were expressed that these 'unfit' people would be a drain on the nation's resources, an idea confirmed by the large number of British recruits who were rejected for armed service during the Boer War (1899-1901). Contemporary ideas and scientific development, especially Darwinism (alongside its more maligned cousin eugenics), lent intellectual credence to the idea that Britain's 'racial stock' was in decline. Particular attention was paid to the problem of inheritance and social problem groups, such as the poor and the 'criminal classes'. These events placed a premium on the behaviour of women as 'guardians of the race'. The First World War magnified and intensified these issues.

At the outbreak of war, contemporaries testified to the explosion of 'khaki fever'. 'Khaki fever' describes the excitement that young girls and women were believed to experience at the presence of soldiers as a wave of patriotism swept across the nation. While 'khaki fever' died out quickly, as the reality of war hit home, concerns lasted throughout the war about the behaviour of these women and young girls. Concern centred on their relations with soldiers. Curfews were placed on towns where large bodies of troops were stationed. In 1918 the notorious regulation 40d was promulgated under the Defence of the Realm Act 1914. This made it a criminal offence for any woman with venereal disease to solicit or to have sexual intercourse with a man.

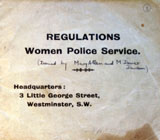

This concern with the behaviour of young women and girls provided an opportunity for feminists to press their case for the need for women police. Two groups of women organized patrols to deal with these wayward women. The more radical of the two was the Women Police Service (WPS) set up by Margaret Damer Dawson and Mary Allen; both had links with the militant suffragette Women’s Social and Political Union. The WPS adopted an interventionist style of rescue work, warning errant girls and soldiers' wives of the danger of immoral behaviour. The women involved in these patrols were issued with a uniform and were to adhere to a strict code of conduct. As can be seen, the regulations followed a strict line, similar to that of the male police, regarding talking on duty, punctuality, the need to avoid accepting 'tips', and the dangers of 'gossiping'.

The other group of women police were the voluntary patrols co-ordinated by the middle-class National Union of Women Workers (NUWW); few of its members were militant feminists. Indeed, the NUWW was reluctant to employ women who had been arrested during suffragette demonstrations and protests. Unlike the WPS, these voluntary patrols tried to disassociate themselves from any ideas of 'rescue work' and charity, and saw themselves as aides to the established police. Both groups of women spent a great deal of time policing the behaviour of working-class women, patrolling parks and public spaces, separating courting couples, and moving on 'dangerous' women. The WPS even signed a contract with the Ministry of Munitions to police the growing number of women workers in munitions factories. Crucially, these women did not possess power of arrest, though they would present evidence in court on the behalf of male officers.

WPC 18 Ellis and Inspector Clayden patrolling outside Bow Street Police Station, 1924.

WPC 18 Ellis and Inspector Clayden patrolling outside Bow Street Police Station, 1924.