Dividing walls

Here are some problems I developed for NRICH on disconnecting sets of points.

Introduction

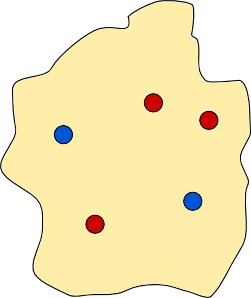

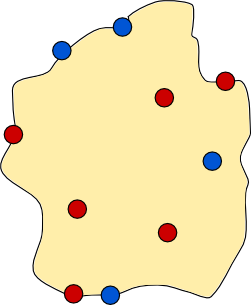

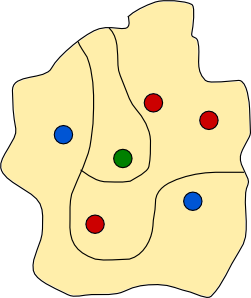

There is an island, shown below, which contains five towns, each marked by a coloured disc. The people from the red towns are arch rivals with the people from the blue towns, so they decide to build a wall to separate all the red towns from all the blue towns. The red towns want to stay in contact with each other so the wall must not separate two red towns. Likewise the wall must not separate blue towns. The wall must be continuous, it must not intersect itself, it must not split, and each end of the wall must be at a point on the coast. Let us call such a wall a dividing wall.

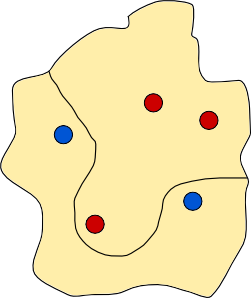

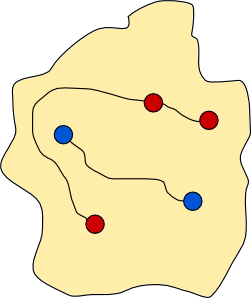

Is it possible to construct a dividing wall? Yes, one is shown below.

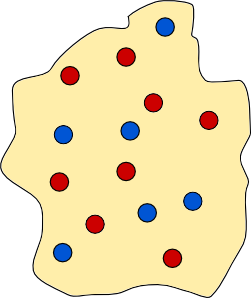

Is it possible to construct a dividing wall for the new collection of towns, shown below?

If you manage the above example, then perhaps you can answer the following question. Given any configuration of red and blue towns, is it always possible to build a dividing wall?

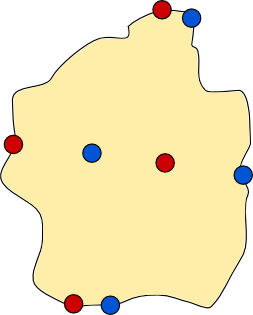

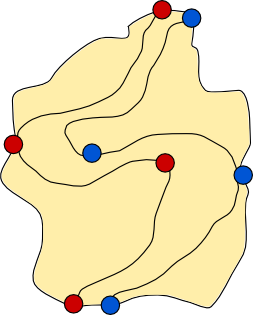

Coastal towns

The next island (below) has coastal towns. These towns differ from all previous towns as you cannot encircle each one with a wall. Can you separate the red and blue towns with a wall in this example?

Have you managed it? If not then persevere; it is possible! Try the next example.

If you cannot build a suitable wall for the previous example then try to answer the following question. What is the simplest configuration of towns, both coastal and inland, for which you cannot build a dividing wall?

Once you have answered that question you may try this harder question. Can you characterise those configurations of towns for which it is possible to build a dividing wall?

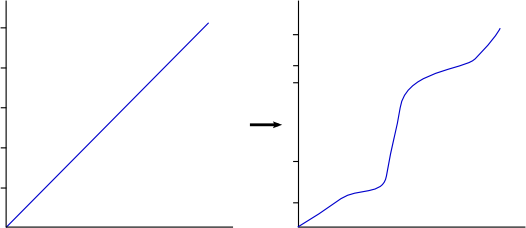

Building roads

History is littered with examples of dividing walls that have contributed to war and misery. Let us suppose that the people from our five original towns are more enlightened, although retain their animosity towards each other. Rather than building a wall, they decide to build two roads. One road connects all the blue towns, and the other road connects all the red towns. The two roads are not allowed to intersect themselves, or each other. The blue road starts at a blue town, and then passes through each of the other blue towns, finishing at a blue town. Likewise for the red road and the red towns. Let us call a pair of such roads connecting roads. An example of a pair of connecting roads is shown below.

Here is a pair of connecting roads for the first coastal town example.

Are the problems of building a dividing wall, and building a pair of connecting roads, related?

More towns

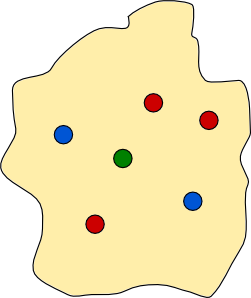

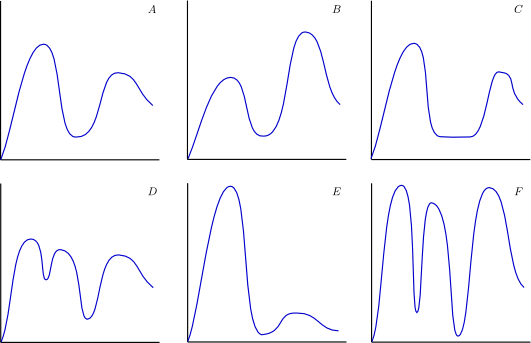

Recent immigrants to the island have set up their own green town. The unfriendly locals quickly found reason to dislike them, and now the dividing wall must separate red towns, blue towns, and green towns.

It is impossible to separate all three sets of towns with one dividing wall. We need another! The rules for two dividing walls are that they must not intersect each other, and each end of each wall must start either from a point on the coast, or from a point on one of the other walls. We can separate red from green from blue with two dividing walls, as shown below.

We can bring in green coastal towns too, and address the next question. Which configurations of red, green, and blue towns can be separated by two dividing walls?

Questions and answers

Questions. Does the shape of the island affect the problem? How about if we introduce lakes to the island, across which neither walls nor roads can be built? We can allow more roads and walls. Does that actually help? We can introduce more towns too. Also, we can assume that the island is a sphere, rather than a disc shape. (That is, we can ask the same questions for people on the whole Earth.) Or we can assume that the people live on a torus. Unlikely, but don’t let that hold us back. We could consider multiple islands, and build bridges between them.

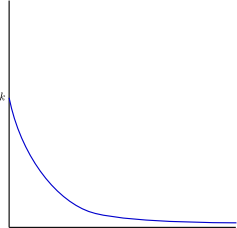

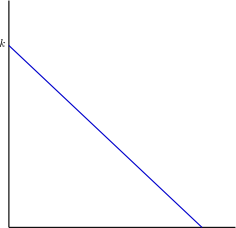

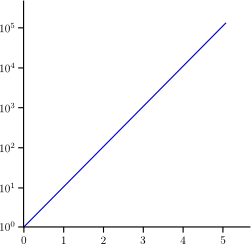

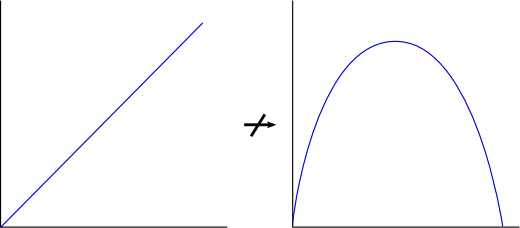

Answers. I haven’t worked out all the answers! The shape of the island doesn’t matter, so we may as well assume it is a disc. Lakes have no impact; we can shrink them down to points without affecting the problem. For two colour types, if there are no coastal towns then a dividing wall exists. If there are coastal towns then a dividing wall exists unless there are four coastal towns that occur in the order red, blue, red, blue, clockwise around the island. Connecting roads are the same as dividing walls. The reasons are similar, if not exactly the same as, the idea in metric space theory of equivalence of path connectivity and connectivity. I don’t imagine that extra walls would help with the two coloured towns problem. For n colour types, and n-1 dividing walls, I suspect that for successful configurations, same coloured towns must be grouped together round the coast.