The John Stephen Kassman Memorial Essay prize is an annual award based on the income from a donation given by the late Alec Kassman in memory of his son. Alec was an Arts Faculty Staff Tutor in the London Region and a contributor to Classical Studies modules. The prize is open to all current Open University undergraduates, who are invited to submit a 3,000 word essay on any aspect of Greek and Roman antiquity.

We’re delighted to announce that the winners of the 2020 John Stephen Kassman Memorial Essay prize and the titles of their essays are as follows:

First prize: Steven Vitale, ‘The Case of the Missing Toponym: A Reinterpretation of the Archaeological Evidence at Iron Age Lefkandi’

Second prize: Patrick Bell, ‘Plague and pandemic; echoes down the ages’

Third prize: Lisa Fortescue-Poole, ‘The Metamorphosis of Pygmalion – scientists and sex-robots: the re-creation of Ovid’s myth in contemporary science fiction’

We asked each of our prize-winners to tell us a bit about their essays and about their OU study journey so far:

Steven: ‘I am in the second year of my studies with the Open University, on track toward a BA in Classical Studies. Though I have a university education in science, this is my first formal opportunity to study the Arts and Humanities, my first time studying through a distance learning program, and my first time studying with a British University. I grew up, and still live, in the United States where distance learning is not popular (present pandemic circumstances excluded) and there is no real alternative to a traditional, residential learning experience for a field such as Classical Studies. The program offered by the Open University is ideal as I can perform my studies interleaved between the responsibilities of work and parenting. I hope in the future to be able to combine my background in science with my study of the classical world to be able to answer archaeological and art historical questions through advancements in forensic technologies.

My Kassman essay addresses a problem I find personally vexing. Lefkandi is an Iron Age settlement on Euboea, Greece, which has been the subject of excavation from the 1960’s through the present day. The archaeological evidence at Lefkandi is extraordinary for its period, including gold jewelry, valuable foreign imports, and monumental architecture. It is not an overstatement that Lefkandi has re-written the previous understanding of a depopulated and impoverished Greek “Dark Ages.” The problem is: this apparently important settlement is no where attested in ancient sources. Lefkandi is a modern name. How can it be that the wealthiest city of the Greek Iron Age has completely disappeared from ancient texts? In my essay I suggest this apparent mystery is due to a misinterpretation of the archaeology. One can show that essentially all of the extraordinary finds are concentrated in one location on the edge of the excavated area, which likely represents a cemetery and ritual centre for wealthy landholders whose estates were distributed throughout the Lelantine Plain. The remainder of the settlement is actually not so remarkable and could plausibly have been ignored by history.’

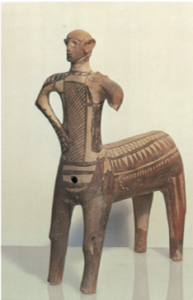

Lefkandi centaur, from Lefkandi I. The Iron Age. Text. The Settlement

Patrick: ‘My OU studies in classics represent longstanding unfinished business. At school in the 1960s opting for science subjects meant dropping Latin and much else. My interest in classics was kept alive as I encountered all sorts of connections whilst studying and later practising medicine. When retirement came 4 years ago, embarking on a BA in Classical Studies was an easy choice. It turned out to be a great experience, not least because of uniformly excellent tuition and support. I completed my degree earlier this year and, when the final assessment was cancelled, had time to enter the Kassman Essay Prize.

In the year of coronavirus I used the benefit of a medical background to examine how ancient Greek literary sources dealt with plague. It soon became clear from the chosen sources, Homer’s Iliad, Sophocles’ Oedipus the King and Thucydides’ History, that the attitudes and responses of the ancients are still relevant today. Specifically we see the same mistakes being made: explaining events in entirely irrational ways, indulging in a toxic blame culture and avoiding difficult political decisions.

I have taken a break from OU studies since the summer, but have been recruited by my old medical school in Belfast to deliver a talk on ‘The Legacy of the Classics in Medicine’ in one of our undergraduate special study modules. I hope there may be other opportunities to demonstrate the importance of classics to the next generation of doctors.’

Plague in an Ancient City, Michiel Sweerts, c. 1652–1654

Lisa: ‘I am currently in my final year of a Classical Studies degree with the Open University, pursuing a lifelong passion. In my first careers interview at school, I said I wanted to be an archaeologist and despite being an English teacher for twenty-five years, I still think there’s time!

I began the course very much focused on ancient Greece, having lived and worked in Greece as a teacher many years ago. I found, however, that the course introduced me to the wonders of Rome, which I am now equally passionate about in terms of Ancient History. My personal area of interest are the constructions of narratives: whether Homer, Ovid or Augustus, the inclusions and omissions, the focus and purpose of each construction. Fascinating too, and connected to this, is the use of myth and its modification in everyday contemporary society.

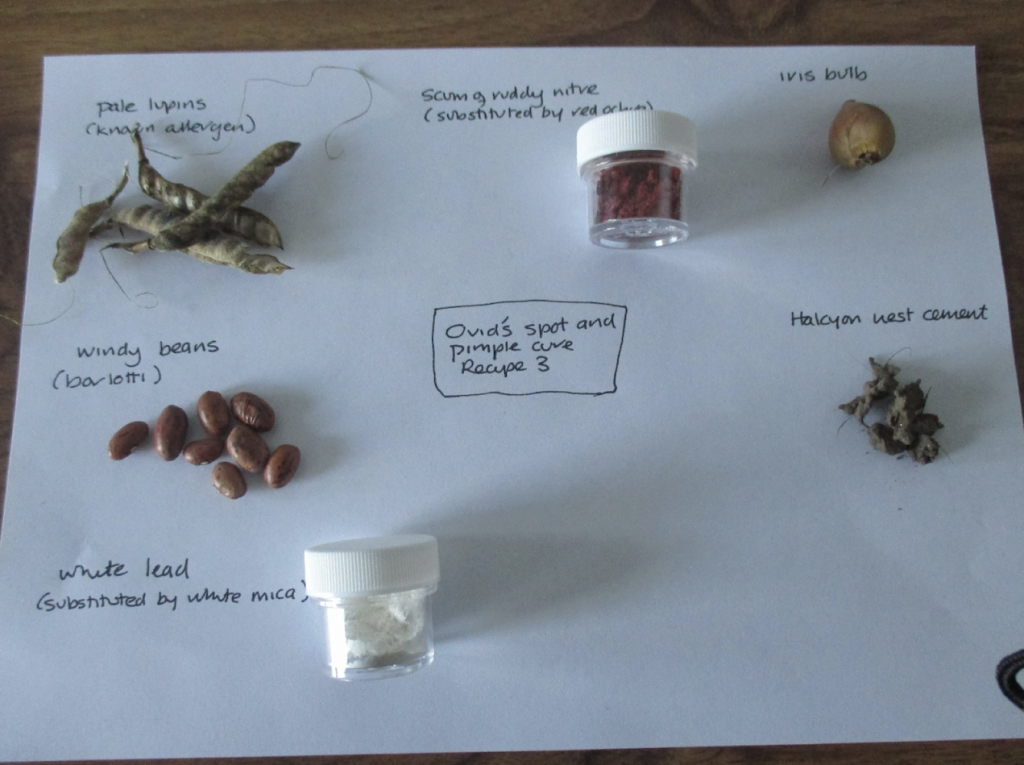

Inspired by Paula James’ discussion of Pygmalion in Buffy the Vampire Slayer in A330 and being an avid fan of contemporary science fiction film, it occurred to me I had seen this myth rendered more darkly and this provided the basis for my essay. I have recently seen another area: video games, which also explores classical history and myth, namely Assassin’s Creed. Time allowing, I will pursue this; it does involve playing video games, too, another hobby! It’s fascinating how strikingly relevant classic is.’

The evolution of Pygmalion in Blade Runner 2049

Congratulations to the winners, and thank you to everyone who entered the competition – we really enjoyed reading all your essays!

![150hornblower[1]](https://www.open.ac.uk/blogs/classicalstudies/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/150hornblower1.jpg)

![v2a21923[1]](https://www.open.ac.uk/blogs/classicalstudies/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/v2a219231.jpg)

, I’m now approaching the big half century and I’m a freelancer in the aviation industry, having previously served in the RAF. Before joining the OU I had no experience of university level education, having left school at sixteen with a clutch of ‘O’ levels. A trip to Rome reignited my childhood interest in the classical world and I began to read more about it. This was the point at which, with some trepidation, I decided to give the OU a go, over twenty five years since I’d written more than a couple of sentences together, never mind an essay!

, I’m now approaching the big half century and I’m a freelancer in the aviation industry, having previously served in the RAF. Before joining the OU I had no experience of university level education, having left school at sixteen with a clutch of ‘O’ levels. A trip to Rome reignited my childhood interest in the classical world and I began to read more about it. This was the point at which, with some trepidation, I decided to give the OU a go, over twenty five years since I’d written more than a couple of sentences together, never mind an essay!