Alison Daniels is an OU student working towards the Q85 BA in Classical Studies. This autumn, she was awarded the ‘highly commended’ prize for her submission to the John Stephen Kassman Memorial Essay competition: an essay entitled ‘Practical Classics: Reflections on the attempted recreation of the ancient Roman skincare and cosmetic products described by Ovid in his Medicamina Faciei Femineae’. Alison attempted to recreate some of the lotions and potions that Ovid recommended to his Roman readers. It’s safe to say that this is the first student essay to arrive in the OU Classical Studies mailbox complete with pots of cosmetic samples!

In this blog post, she tells us a bit more about the process of researching and writing the essay, and her plans for future work in the field of Classical Studies.

—-

Hello Alison, congratulations on your prize! Please could you introduce yourself to our blog readers, and tell us about your OU learning journey so far?

This is my second degree with the OU. The first was an Open Honours degree which ended up as a weird mixture of cognitive psychology and Romans. I just chose what interested me. My love for the Romans was rekindled by the sight of James Purefoy’s backside in HBO’s Rome on TV. It’s not the greatest reason for studying, is it? This time I’m taking another honours degree in Classical Studies. Last year I had to exert some discipline to learn all those Latin endings and declensions for A276. I’m now taking A330 looking at Greek and Roman Myth. I can’t quite get my head round the Greeks, they seem to have quite an alien mind set to me.

I’d love to go on and take a PhD part time by distance learning, but funding it would be an issue. Building on A330, I’m fascinated by how Roman cults functioned as businesses, so that would be my subject. How cults competed, attracted new members and got the money to operate, how they entered a new market, how you spread the message about your “new” god, why people would join a new cult and what it offered, how they sought out high profile converts, the economics and business aspects of creating and buying votives – that kind of thing.

Other than that, I’ve always had way too much curiosity and a bad habit of going, “What if…”

You chose to write your Kassman essay about Ovid’s Medicamina Faciei Femineae. Can you give us some background to this text? How much of it survives, and what is it about?

What remains of the Medicamina is just a fragment of about 100 lines long. The first half is Ovid’s usual poetics, but the second half changes quite abruptly to a series of five recipes for skincare and cosmetic products. At first sight, it didn’t seem to fit with the bits of Ovid I’d encountered on the module [A276]]. It was as if, say, Hamlet broke off in the middle of “To be or not to be” to give you his recipe for Danish Pastries.

Why you decide to recreate the recipes, rather than just read about them? And what did you expect to find out when you started your research?

When I started my research, I thought I’d find that lots of people had recreated Ovid’s recipes. It seemed such an obvious approach, but although there were lots of references to the recipes, no what seemed to have actually tried them out. Even where people had written books on Roman cosmetics, they didn’t seem to have made them, so I decided I’d give it a go as my topic for the Kassman essay prize.

How many recipes did you recreate? What were the main challenges you encountered?

I chose to recreate four recipes out of the five. The one I omitted involved nitre, which I thought at the time I’d have to make by following a medieval process. Since it involved digging a metre cubed pit and filling it with alternate layers of lime and chicken poo, I passed on that.

There were two main challenges. I soon discovered why no one appeared to have recreated Ovid’s recipes before! The first was the translations themselves, which varied enormously and unexpectedly. Take lines 78-80. Mahoney (Perseus.tufts.edu) renders them as:

“Two ounces next of gum, and thural seed,

That for the gracious gods does incense breed,

And let a double share of honey last succeed”.

This differs significantly from the prose translation offered by May in the Loeb,

“There should also be added two ounces of gum and Tuscan spelt, and nine times as much honey.” (www.sacred-texts.com/cla/ovid/lboo/lboo62.htm).

So I didn’t really know whether to go with nine times as much honey or 4 ounces as the double share. Scale it up to fifty lines and it becomes even less consistent. In the end I opted for the Loeb translation throughout, cross-referencing as needed.

The second challenge was rounding up the materials and trying to identify what species of plant or type of material Ovid actually meant. He was writing before scientific taxonomy and many of the translations seemed give priority to metre over product formulation. In one recipe he specifies windy beans, but even with research into ancient Roman recipes, it wasn’t clear which variety was meant. Add in that commercial plant breeding and agriculture has changed the physical qualities of many species over time and I couldn’t be sure that Ovid’s opium poppy petals bore much resemblance to the ones from my neighbour’s garden, or that the modern ingredients wouldn’t result in a less efficacious product.

I had to make some educated guesses and substitutions, so I used Scottish barley that a local farmer let me have rather than Libyan barley and my iris bulbs came from the garden centre rather than Illyria. Similarly, I used a high powered blender to grind and mix my ingredients since I had no access to strong-armed slaves or a donkey powered mill.

Can you give us a taster of one of the recipes – perhaps your favourite one?

Although Ovid’s fennel seed complexion cream smelt fabulous, I found his spot and pimple cream most interesting. At first, I thought it was maybe a later addition to the poem as the quantity of ingredients seemed pretty industrial, coming in at just over 4Kg.

At Ovid’s stated dose the batch contains six months’ worth of daily treatment. In fact, Ovid’s suggestion of ½ Roman ounce, or 14.35g per treatment, is 29 times higher than a recommended full face dose of a modern acne treatment. At that rate, Ovid’s recipe provides almost six years of twice daily treatments. I thought Ovid was obliquely suggesting that those with spots should cake themselves in a thick layer of disguising cream for several years until the skin problems have passed.

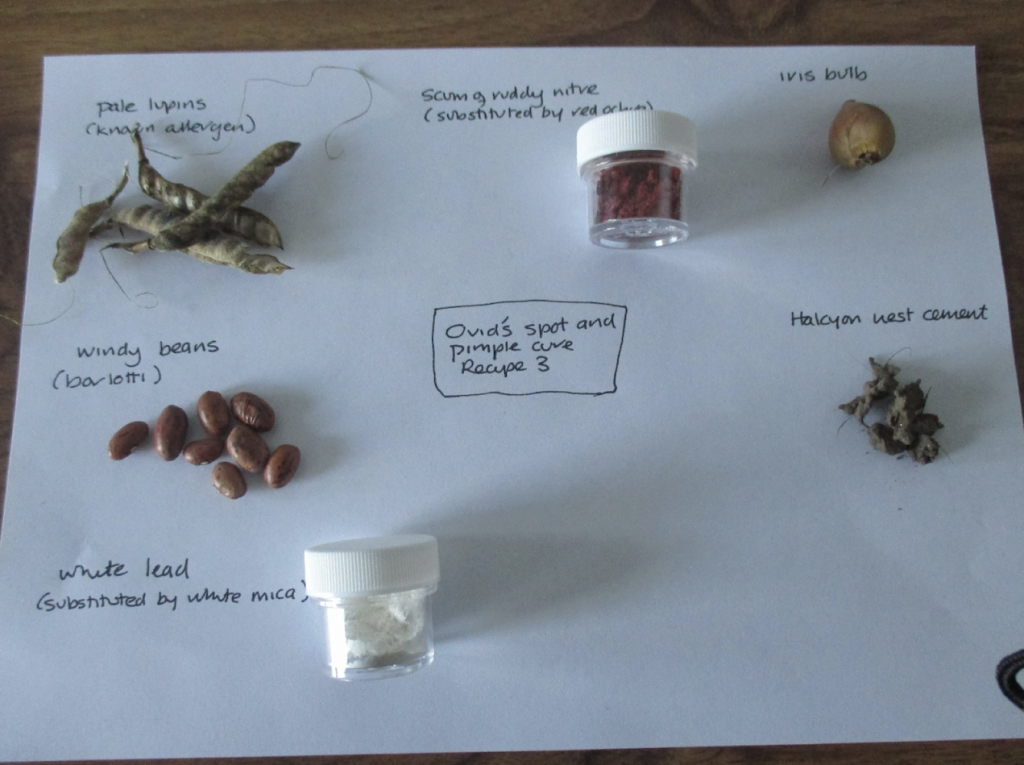

Ingredients for Ovid’s spot and pimple cure and the end result

When I tested the recipe, I found it resulted in a dark, flecked mixture. It didn’t absorb into the skin, but sits on it until removed. Rubbing resulted in the honey component spreading into the skin, leaving dry farinaceous matter on top. It is exceptionally drying on the skin, but not sticky. If Ovid’s suggested dose of an ounce were applied to the face, it would doubtless slide off. The wearer would not be able to apply this product then appear in public, but would have to stay secluded. Ovid often seemed to use a known allergen in this preparation. Lupin commonly causes skin rashes and breathing difficulties in around 1-2% of the population.

You mention in the essay that some of your neighbours helped with sourcing the ingredients – what did they think when you told them about your project?!

Luckily for me, I live in quite a charmingly eccentric little village, where people are always helping each other out. My job writing for magazines and editing means my neighbours are quite used to me doing strange things, like walking over hot coals or trying twenty ice cream flavours in one afternoon for a food review! They didn’t have a problem with letting me take some lupin seeds or stealing all the petals from their poppies once I had explained.

And finally, what would you count as your most important or surprising discovery?

Even though the project was pretty poor science and not very rigorous as classical research, I think it had value. It gave me an idea of the difficulties of primary research without proper funding, equipment and access to materials and secondary research. It was also fun to do and interesting to explore.

In terms of the cosmetic formulae themselves, I came to the conclusion that Ovid gives us a series of cosmetics where each has the opposite effect to that promised. A cheek stain that gives the wearer the appearance of bruises rather than a healthy glow; a spot cream that needs to be layered on so thickly the wearer’s entire visage is obscured and the user must avoid others; a cream that promises radiance but soon leaves the skin dull and grey and a brightening cream which blisters the skin.

While this may have been Ovid’s subtle comment on the futility of artificial beauty products, my own conclusion was that the recipes were, in effect, a series of practical jokes. By simply translating Ovid’s words and failing to fully comprehend the sly implications of his recipes, I felt we may have missed out on a more practical aspect of Ovid’s humour.