From the morbid to the romantic: today we are headed from Juliet’s tomb to Juliet’s house, the site from which those wonderfully poetic declarations of love, so frequently quoted even to this day, were supposedly expressed and received from the balcony. The day I visited, the courtyard was solid with young tourist-lovers, and I’m afraid that I probably spoilt a lot of photos by standing on the famous balcony. More Lady Capulet than Juliet these days, and even that is quite a self-flattering stretch.

‘Juliet’s house’ begins to appear at much the same time as Juliet’s tomb, and for much the same sentimental, picturesque and national reasons. Samuel Rogers had sought it out in 1822. Recording the experience of finding the building in his much-quoted poetic travelogue Italy (1822-28), and making it plain that the house’s aura is for him specifically Shakespearean, he declared: ‘The old Palace of the Capelletti, with its uncouth balcony and irregular windows, is still standing in a lane near the Market-place… what Englishman can behold it with indifference?’ In the late 1840s, the Baroness Blaze de Bury and her party came in search of Shakespeare’s Verona, and engaged in the sort of imaginative experiment typical of the literary tourism of the time. Blaze De Bury insists on the ‘truth’ of the story of Romeo and Juliet to Verona in a number of ways, adducing archival chronicles and comparing Shakespeare’s plays to the original Italian stories. But her main system of authentication is the felt power of poetry to transform place. The house must be authentic, she argues, because she experiences it as authentic: ‘Why, if you will but take the trouble of listening, you may hear them within calling “for dates and quinces in the pantry”; and as the evening shadows fall, masque after masque goes by to Capulet’s feast. Never tell me that Juliet dwelt not there, and that it was not through that gateway that Romeo passed…’ she writes in her Germania (1851).

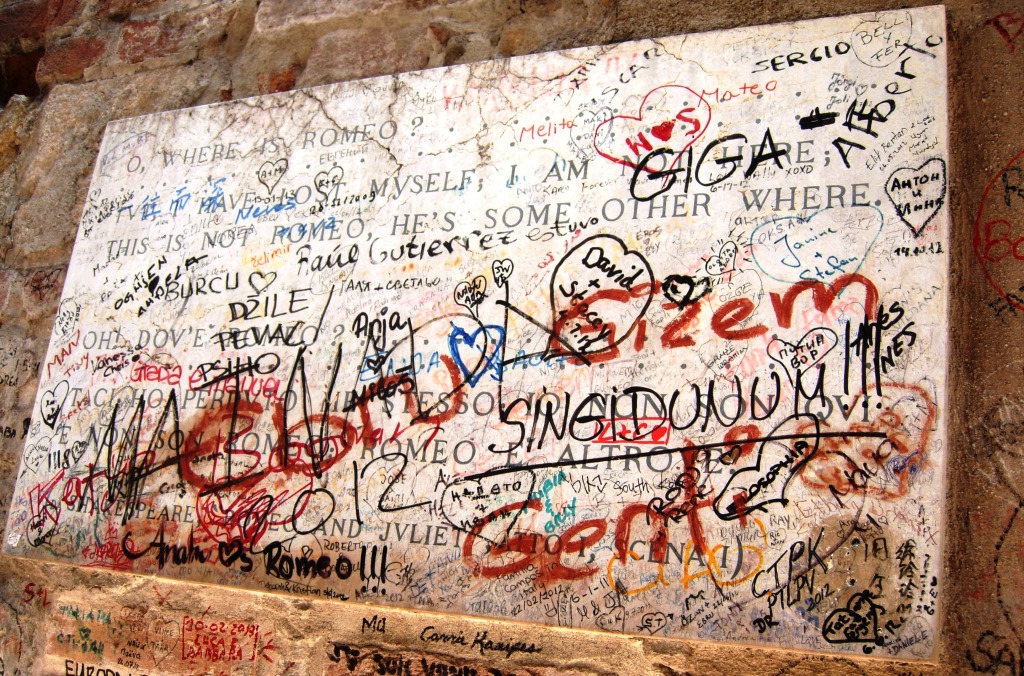

Between 1937 and 1942, Juliet’s house underwent a transformation, resembling that which had slowly overtaken Juliet’s tomb so as to make it look more as it typically did on stage. In 1868, the then Austrian authorities had smartened up the open-air site of the tomb with a modern chapel and a sheltering portico. This process of making the place look more as it had been imagined in other media took a dramatic leap in 1938, when the fascist authorities again repaired and restored the tomb to make it look more as represented by the new hyper-realism of film, and specifically, by George Cukor’s Hollywood blockbuster of Romeo and Juliet of 1936. The tomb was placed in a brand-new, purpose-built crypt, a garden and approach ornamented with benches, columns, fountains and trees was provided, and this (setting aside the addition of all sorts of monuments, sculptures and artworks and the annex exhibition) is essentially how the tomb is situated today. In a similar fashion, the palazzo was provided with a rose-window, a gothic-style doorway, and a balcony on which sits something said to be either a coffin or a water-trough. Since then the house has continued to evolve towards further realism, driven by Franco Zeffirelli’s on-location filming in 1968. Innovations have included the exhibition of Zeffirelli’s costumes, a replica of ‘Juliet’s bed’, and the installation of a life-size bronze of Juliet herself in the courtyard in 1972.

By the mid-nineteenth century, Verona was providing a place to understand Shakespeare as global, where admirers of all nationalities could encounter Shakespeare while insisting on the discrepancy between a true appreciation of the poetry of Shakespeare as experienced on the page and the credulous literal-mindedness of tourism. All the same, the growing realism of stage and film drove successive changes to the actuality of Verona from the late nineteenth century onwards.

Although there are clear continuities between the Victorian view of Verona and modern day sensibilities and practices, what is striking is the extent to which Verona is not really Shakespeare’s, but altogether Juliet’s. Verona has erected at least three busts of Shakespeare, one at the gate through which Romeo flees the city and two at the site of the tomb; but it has to be admitted that busts of him have rarely looked more magnificently sheepish, creepily middle-aged, and altogether parentally and embarrassingly beside the point. The statue the tourists want to see and to touch and to be photographed with, is always Juliet’s. Indeed, as of 2014 that statue was replaced by a replica because of extensive damage caused by the tourist custom of touching her breast to ensure good fortune in love, a modern instance of that nineteenth-century investment – touched on in my last post (https://www.open.ac.uk/blogs/literarytourist/?p=171)- in proximity between the tourist body and that of Juliet.