In my last few posts I’ve talked about what it was that romantic and Victorian visitors brought with them, and left behind, when visiting writers homes and haunts. Today we shall explore the third and final part of this trilogy: what the tourist took away. (I have a weakness for tea-towels, myself, even though I do have a dishwasher). Just like today, nineteenth-century tourists typically brought back with them mementoes by which to remember their visit. The very cheapest and easiest thing to take was a flower or leaf, which you could press between the leaves of a book.

Although the vast majority of this material is now lost, a very large cache still exists in the albums of Mrs Emma Shay, a redoubtable sixty-four year old retired college English teacher from Wessington Springs, North Dakota. On release from her long years of inspiring literary taste in the young, Mrs Shay conceived a desire to tour the literary landscape of Britain. Over the course of three months in the summer of 1926 she sailed to Britain, and visited, wait for it George Eliot’s birthplace on the Floss, Burns’ birthplace at Alloway and the bank of the ‘bonny Doon’, Shakespeare’s birthplace and grave and his ‘country’ around Stratford-upon-Avon, Tintern Abbey on the Wye in homage to Wordsworth, Tennyson’s house Faringford on the Isle of Wight, Gray’s grave at Stoke Poges, Milton’s house in Chalfont St Giles, Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey, Pope’s house at Twickenham, Walpole’s Strawberry Hill, Bunyan’s birthplace, Cowper’s home in Olney, Keats’ home in Hampstead, Dickens’ home at Gad’s Hill, Byron’s home at Newstead Abbey, Wordsworth’s houses at Dove Cottage and Rydal Mount, Felicia Hemans’ house close by, Robert Southey’s home in Keswick, Ruskin’s home at Coniston, Burns’ Country in Ayrshire and Dumfries, and several sites associated with Sir Walter Scott, including Kenilworth, Abbotsford, Melrose Abbey, and Loch Katrine.

Shay proposed to fund her trip by subscription through the college; it would be possible to participate vicariously in her adventure for $5. Her letter announcing the project makes clear what she thought would sell the idea: subscribers were promised a ‘mountain daisy’ from Burns’ birthplace, ‘a yellow primrose from the Lake Region’ or ‘a snapshot of some spot dear to lovers of literature’. This, along with her manuscript diary and the albums themselves, suggests the importance of choosing the most sentimentally or poetically appropriate flowers available for the setting. In response, some forty friends and well-wishers provided money up front in exchange for a promise that she would make up forty identical albums of photographs plus associated pressed plant-material collected from the sites she planned to visit.

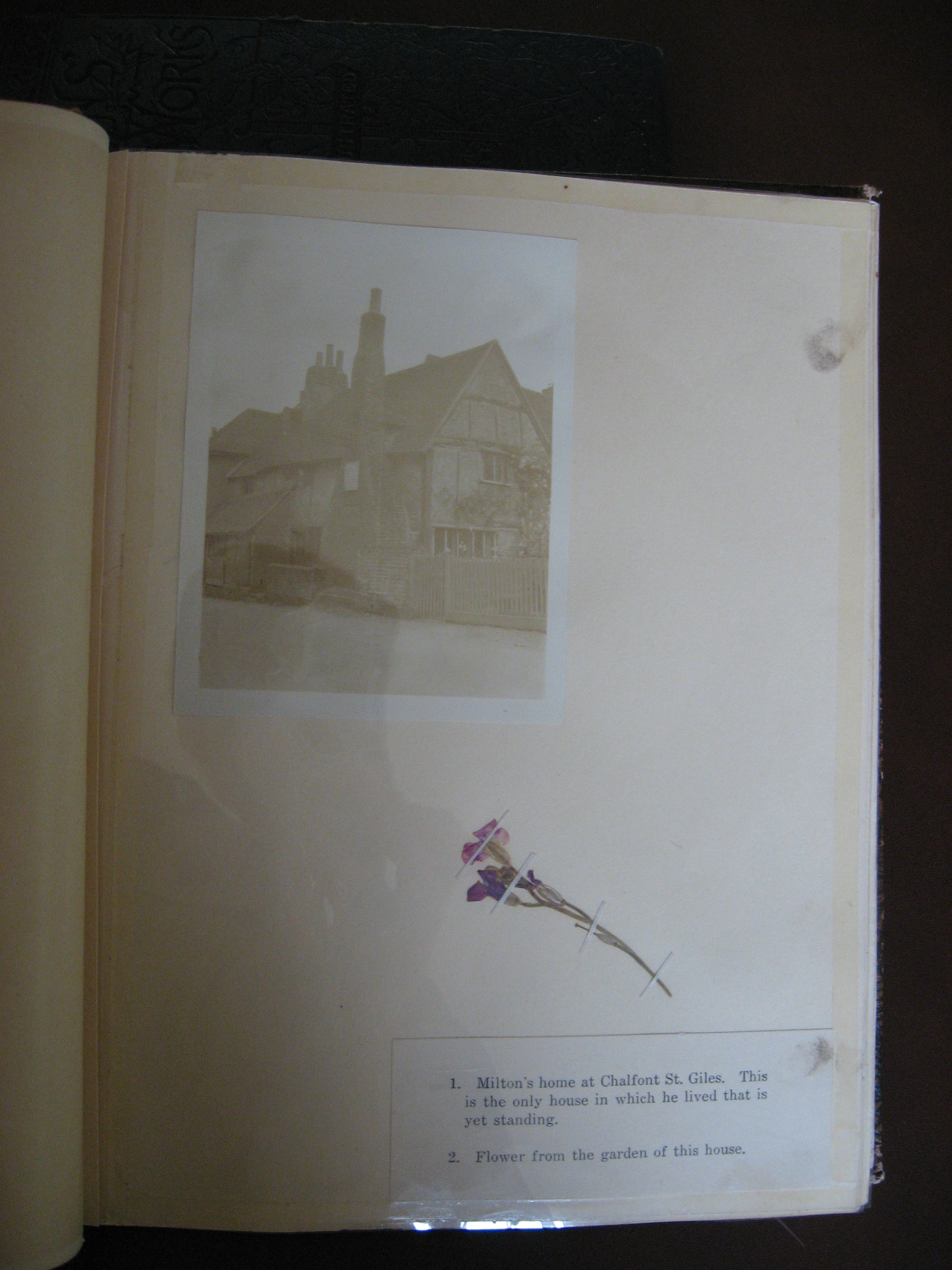

The surviving albums devote a page to each literary location. Each page is made up of a photograph of the location, a plant specimen, and a caption detailing the provenance of the plant and, more importantly, its biographical and often poetically allusive import. Included are a leaf from the tree under which Keats wrote ‘To a Nightingale’, ‘privet from the hedge of Tennyson’s lane where he loved to walk’, ‘flower from a ‘crannied wall’, Tennyson’s Lane’, ‘Bark from old yew tree under which Gray sat when writing his elegy’, and a leaf from a syringa bush at Dove Cottage ‘planted by [Wordsworth]’. The sheer scale and enterprise of Mrs Shay’s activities in Stratford-upon-Avon alone — forty daisies from Holy Trinity churchyard, forty leaves from the garden at New Place, forty specimens of flowers from the inspirational banks of ‘Shakespeare’s river’, pansies and rosemary from the environs of Anne Hathaway’s cottage, and forty clover leaves from Mary Arden’s house – gives some sense of the exhausting travelling, the predatory botany and the quantity of the required in-transit flower-pressing that on occasion nearly defeated and often exhausted even the evidently intrepid Shay.

The albums were eventually handsomely bound as ‘Floral Souvenirs of English Authors’ and duly distributed. Those that survive are now kept, under the aegis of the local Shakespeare Club in Wessington Springs, in the house she built for her retirement on her return. This is a would-be replica of Anne Hathaway’s Cottage, copied by local workmen from a postcard brought back by Mrs Shay. (Since the postcard shows the original from only one angle, the replica, it has to be conceded, only really resembles it at all when viewed from that angle). Around it, there spreads one of America’s many ‘Shakespeare gardens’. The whole, then, is an exercise in bringing the materiality of Shakespeare ‘home’.