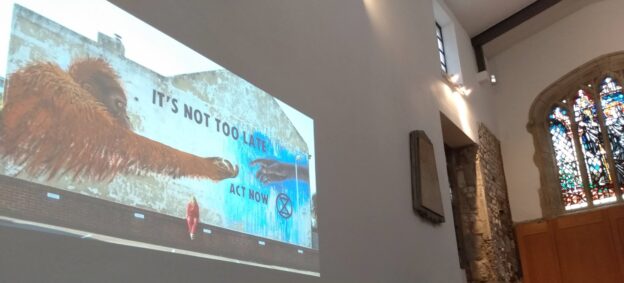

Although we are often told that late modernity is self-reflexive, and grounded in self-examination this reflexivity has been critiqued from many quarters for its “ouroboric” tendencies, or for not being grounded in social practice.¹ It is as though, with the advent of what Peter Berger called the ‘shrinkage’ of the sacred, or Max Weber called ‘disenchantment’, there were fewer and fewer vistas for sustained collective reflection—‘Sorry folks, all we have left is this small bottle of individual self-exploration leading to an intoxicating search for self-identity. It may look small, but it is bottomless…’ No wonder that only something as collectively sobering as the climate crisis could bring about the new ‘elusive virtue’ of ecological reflexivity, with its components of ‘recognition, rethinking and response’ (Pickering 2019), or as Extinction Rebellion encapsulates it: ‘Act Now’.

The 2018 reboot of the climate movement, Extinction Rebellion (XR), seems to have already accomplished the impossible by carrying through elements from the long 1960s transatlantic counterculture, to green millennials. When XR activists talk about REGEN—the regenerative culture project at the heart of XR—you can hear reverberated echoes of the alternative communes and free festivals, which seemed to have either become distant history or, may have been gestating inside new global transformative festivals (St John 2022; van den Ende 2022). Art and performance festivals had indeed preserved elements of the counterculture, but the protest spirit of the 1960s hippie culture had entered a dormant, performative, and memorialized phase (Nita and Gemie 2020). Sure, the so-called ‘long 1960s’ culture might be remembered and celebrated for two short weeks at Glastonbury or Burning Man, but could a new generation be living it out?

REGEN (short for ‘regenerative culture’) recaptures the ethos of civil disobedience, artistic activism, and communalism of the early hippie communes which were anticipating and preparing themselves for a future world in deep crisis (Miller 1999). Take for example the four-minute clip below where an XR activist explains this new culture in the making. She describes REGEN as ‘the mycelium upon which XR relies for its nurturing a new society that is resilient and robust and can support us all through the changes we must inevitably face together’. REGEN helps us ‘reweave ourselves as part of a living eco-system’ through climate mindfulness, expressing grief, learning resilience, and experimenting with new types of self-care and communication practices—like ‘listening circles’, gatherings where people listen without directly responding to each other. Surely, these are practices of eco-reflexivity—but where are they coming from?

XR Regen Culture Explained | April Griefsong | March 2019 | Extinction Rebellion UK – YouTube

‘Listening circles’ and other such REGEN practices may seem novel in these new public and increasingly digital spaces, but they have been around for decades, incubating inside intentional communities, 12-step groups, festival cultures, and New Religious Movements. Listening circles would be familiar to those of us accustomed to ‘sharing our experience, strength and hope’ inside the Anonymous community (encompassing Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, Alanon and so on) as well as newly emerging, global, self-help practices and networks, such as ‘Circling’ and ‘Authentic Relating’.

REGEN’s material culture reflects shared physical, sensorial, and performative elements from Eco-Paganism and Green Christianity, discernible in its very fabric—the organisation of place, dress, make up, media, food—and common Celtic aesthetics. Andy Letcher’s ethnographic work of Eco-Paganism in the 1990s British eco-protest culture shows that the Pagan Road protests were influential in propelling radical environmentalism and its methodology of non-violent direct action into the (greater) public consciousness (2002). This heroic type of environmental activism has clear Christian undercurrents: it is millenarian and Tolkienesque: there is a strong narrative of the protest as ‘the last pitched battle of some ancient tribe against the relentless advance of modernity’’ (Letcher 2002, 64).

We can recognise in XR a joint Christian and Pagan inheritance, especially in the affective repertoire embodied by the sacrifice and vulnerability that come with being arrested by the police. Green Christians and Eco-Pagans share their opposition towards modernity, with common roots in the Romantic Movement, and a ‘back to nature’ discourse – which for Christians takes on a more pastoral re-imagining of the Early church. We see these trends quite clearly in the Christian ‘Forest Church Movement’ established in Wales, in 2010, which continues to grow in the UK, becoming increasingly influential among green and liberal Christians, including Christians belonging to XR, or Christian Rebels.

Does this mean that XR and its REGEN project are ‘religious’ or akin to a new religious tradition? Well, everything is a bit religious—given that religious traditions are simply part of the cultural fabric of contemporary society. Christianity has been with us, under various guises, for the past two millennia; we should really be expecting to find it everywhere we look. However, REGEN is quite clearly not only drawing on new spiritual practices, but importantly, it is also challenging and re-purposing contemporary spirituality, as it attempts to overtly shift our attention from ‘the self’ to our ‘ecological selves’. In that, XR is perhaps ushering in a new eco-reflexivity, with consequences for modernity and its solipsistic condition.

NOTES

¹ On modernity and reflexivity, see Benavides, 1998; Bourdieu and Wacquant, 1992. On critiques, see Farrugia and Woodman, 2015; Adkins, 2003.

REFERENCES

Adkins, Lisa. 2003. ‘Reflexivity.’ Theory, Culture & Society 6 (1): 21-42.

Benavides, Gustavo. 1998. ‘Modernity’. In Mark Taylor (ed.) Critical Terms for Religious Thinking. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, pp. 186-204.

Berger, Peter. 1969. The Sacred Canopy. Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. New York: Anchor Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre, and Wacquant, Loïc. 1992. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology. Cambridge: Polity.

Farrugia, David, and Dan Woodman. 2015. ‘Ultimate Concerns in Late Modernity: Archer, Bourdieu and Reflexivity.’ The British Journal of Sociology 66 (4): 626-44.

Letcher, Andy. 2002. ‘“If You go Down to the Woods Today…”: Spirituality and the Eco-Protest Lifestyle, Ecotheology: Journal of Religion, Nature and the Environment 7 (1): 81-87.

Miller, Timothy. 1999.The 60s communes: hippies and beyond. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Nita, Maria and Sharif Gemie, ‘Counterculture, Local Authorities and British Christianity at the Windsor and Watchfield Free Festivals (1972–5)’, Twentieth Century British History 31/1 (2020), 51 -78.

Pickering, Jonathan. 2019. ‘Ecological reflexivity: characterising an elusive virtue for governance in the Anthropocene’, Environmental Politics, 28 (7): 1145-1166.

St John, Graham. 2022. ‘Sherpagate: Tourists and Cultural Drama at Burning Man’. In: Nita M., Kidwell J.H. (eds) Festival Cultures. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 169-193.

van den Ende, Leonore. 2022. ‘Festival Co-Creation and Transformation: The Case of Tribal Gathering in Panama’. In: Nita M., Kidwell J.H. (eds) Festival Cultures. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 195-226.

Weber, Max. 2007 [1946]. From Max Weber. In H. H. Gerth and C. Wright Mills (trans. and eds) Essays in Sociology. New York: Oxford University Press.