By John Maiden

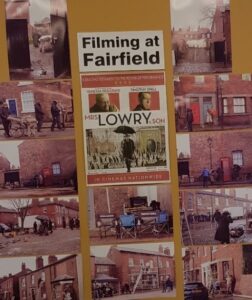

Knowledge and understanding of religious diversity in the past, and historic approaches to toleration and peace, has great potential value for the present. That has been the view of the Open University team involved in the Horizon 2020-funded project “Religious Toleration and Peace” (RETOPEA), and its various “afterlife” initiatives funded by the Open Societal Challenges programme and the Culham St Gabriel’s Trust. This research has resulted in a user-friendly digital archive of over 400 sources, or “clippings” about religious toleration and peace past and present; and a pioneering “Docutubes” methodology which has helped schools and other formal and informal educational partners to encourage young people to think about the past, present and future of religious toleration and peace by making short films. Rather than “just” learning historical facts or assuming there are simplistic “lessons” for the present, this approach has aimed constructively and creatively to assist young people to learn with history – to think like historians and apply this knowledge and understanding to their own lives and contemporary contexts.

The Open University’s John Maiden and Stefanie Sinclair, along with Karel Van Nieuwenhuyse of the University of Leuven, have now published an edited handbook for educators – including secondary school, sixth-form college and university level teachers – on the RETOPEA approach. Teaching and Learning About Religious Diversity in the Past and Present: Beyond Stereotypes (Palgrave) looks at various examples of toleration and peace-making in history, examining nine case studies: the Capitulations of Granada (1492), the Confederation of Warsaw (1573), the Peace of Westphalia (1648), the Royal Charter of Rhode Island (1663), the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1789), the European Convention of Human Rights (1950), the Belfast/ Good Friday Agreement (1998), the Ohrid Framework Agreement (2001) and the Mardin Declaration (2010).

The book provides expert background and analysis of these historical documents but goes further by introducing key sources (“clippings”) – short visual and textual excerpts relating to the document – which are also available on the RETOPEA website. The book, furthermore, offers practical advice on how to engage young people creatively with this history, using the “Docutube” approach. The book makes a strong argument that an understanding of religious diversity past and present is relevant not only for religious education, but for subjects such as history, citizenship and philosophy.