The continent is home to people who identify with a range of different religions and to people who express no religious affiliation.[i] There has never been a time in history when everyone in Europe practised the same religion. Nonetheless, given many centuries of the predominance of Christianity, it has been suggested that Europe’s culture is Christian. One of the proponents of this idea, the Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, has claimed that Europe is under threat from non-Christian migrants.[ii] In contrast, the stated values of the European Union are secular: human dignity, freedom (including freedom of religion), democracy, equality, rule of law, and human rights.[iii]

The opposition between a Christian view of the continent and a secular view is just one way in which there is uncertainty about what Europe represents. There are plenty of others. Picture in your mind the map of the continent. Where is the eastern boundary between Europe and Asia? The responses to this question vary from person to person. Do you include some, all, or none of the Russian Federation within the borders of Europe? What about Belarus, Turkey, Georgia?

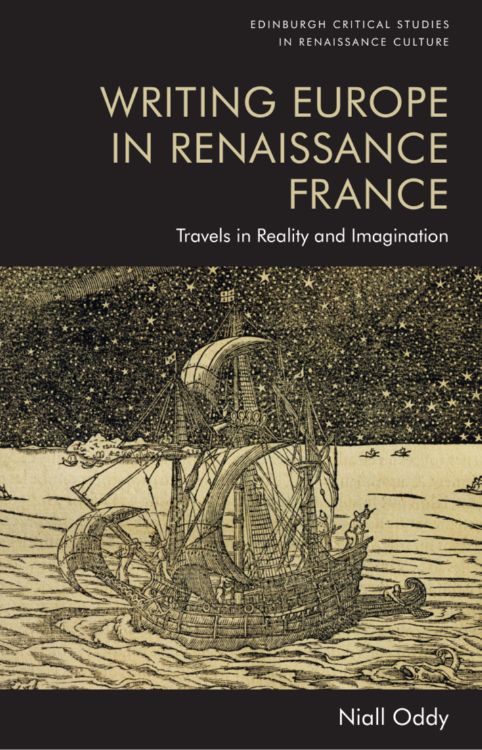

Disagreements about Europe are not new. They have a long history. In my book, Writing Europe in Renaissance France: Travels in Reality and Imagination, I examine debates about Europe as far back as the sixteenth century. This has been regarded as an important period in the development of the idea of Europe for two main reasons. First, this was the age of Europeans’ first truly global encounters, when they started to colonise the Americas and parts of Africa and Asia. This gave rise to a Eurocentric world view, in which Europeans saw themselves as sharing a common culture that was different from, and superior, to the rest of the world. Second, the sixteenth century witnessed the violent conflicts that emerged as a result of the Protestant Reformation. Prior to this, people across the continent had been united by a shared allegiance to Christendom, but this was destroyed as Catholics and the various new Protestant churches turned against each other. As such, Europe began to replace Christendom as a marker of an overarching identity.

Europe, however, did not emerge as a clear, unambiguous concept. Instead, it inherited many of Christendom’s contradictions. Often used by western Christians to refer exclusively to the Latin Church centred on Rome, Christendom was sometimes used to include eastern Orthodox Christians. This inconsistent pattern of inclusion and exclusion was reflected when the word Europe became more common. Sixteenth-century geography books described the people of Europe as stronger and healthier, with a more advanced urban culture, than the people of Asia, Africa and America. They identified the eastern boundary of Europe as the Tanais river (known today as the Don, it flows through Russia into the Sea of Azov), which included most of the Orthodox Christian Tsardom of Muscovy (the much smaller state from which the present-day Russian Federation claims descent), the Muslim Crimean Khanate, and parts of the Ottoman Empire, which stretched as far west as Hungary. However, the same geography books also described Poland, whose rulers were Catholic, as the frontier of Europe, thereby excluding the primarily Orthodox and Muslims lands to the east. Europe was not a neutral geographical concept, but an emotive cultural and ideological marker, the boundaries of which were imprecise.

Writing Europe in Renaissance France focusses on the factors that shaped how people understood Europe differently. Take André Thevet, the Catholic chaplain of a French expedition to establish a colony in Brazil. He praised the Spanish conquest of Peru, calling it ‘a new Europe’. For him, Europe was a cultural model of superiority that justified overseas empire-building. By contrast, Jean de Léry, who also travelled to Brazil, wrote of a Europe ravaged by conflict. He was a Calvinist who fought against Catholics in the French Wars of Religion and did not feel a shared identity with his religious enemies.

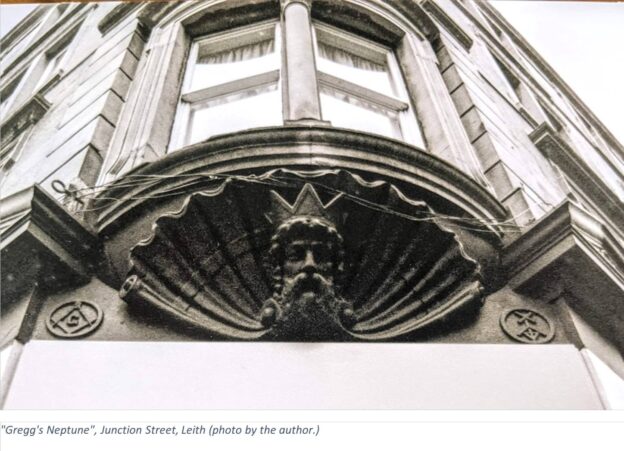

Figure 4 – Bacchus head, Maritime Lane, Leith (photo by the author).

Figure 4 – Bacchus head, Maritime Lane, Leith (photo by the author).