Some months ago, Max Lucado, one of a handful of Christian leaders who since the death of Billy Graham might possibly be said to fall into an ‘America’s pastor’ category, and who has sold well north of 100 million products, revealed that he spoke in tongues in his devotional life. What was perhaps most striking about the news was the absence of any substantial backlash. There was almost a collective shrug of the shoulders, as evangelicals seemed to say, ‘And what?’. The lack of criticism is one indicator of a remarkable shift of charismatic practice, from the periphery of non-Pentecostal Christianity to the mainstream.

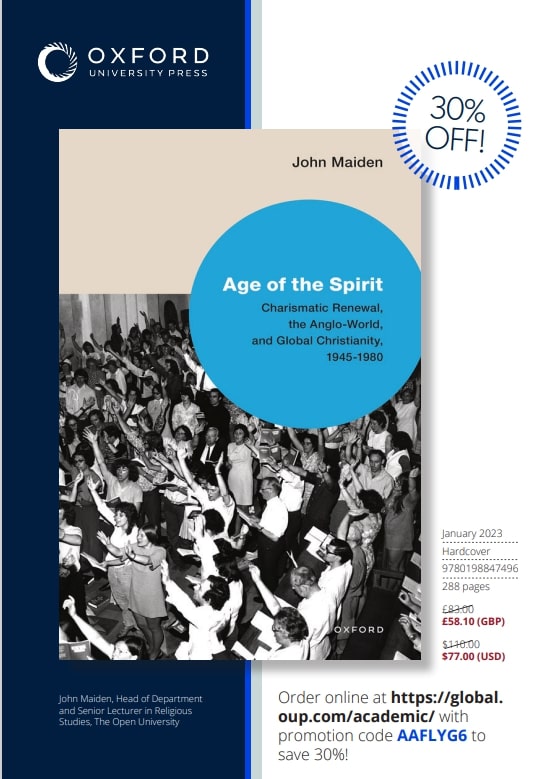

My new book, Age of the Spirit: Charismatic Renewal, the Anglo-World and Global Christianity, 1945-1980 (Oxford University Press) shows that in the 1960s, in English-speaking contexts such as the United States, the situation was very different. It was only six decades since the wider evangelical holiness movement had been riven by the ‘tongues’ controversy, and pentecostals had soon after begun to form their own denominations. In the early 1960s, in Southern California, Morton Kelsey an Episcopalian, described charismatic prayer groups – ecumenical grassroots gatherings where Christians sought to experience the power and presence of the Holy Spirit – as having ‘some of the characteristics of a secret society’ such was the threat of ‘ridicule or censure’. In New Zealand, the historian Peter Lineham described anti-charismatic behaviour in the Brethren churches as comparable to that of McCarthyite anti-communism. In my research, I have often read of, or spoken to people, who were ‘put out’ of their local congregations because they had been ‘baptised in the Spirit’, spoken in tongues, or practiced some other charismatic gift.

How things have changed. Within Anglicanism, there is a charismatic Archbishop of Canterbury. Holy Trinity Brompton, a west London charismatic flagship congregation and birthplace of the Alpha evangelistic course, has become a driving force of Christian witness. As Andrew Atherstone’s (2022) recent research has detailed, Alpha has been packaged as a global brand. Charismatic worship, and ministries such as Hillsong, Bethel and Passion, has dominated the Christian music industry, and songs are frequently to be heard in non-charismatic churches. There is a growing academic literature on independent congregations (including many mega-churches) and phenomena such as the ‘new paradigm churches’, the ‘New Apostolic Reformation’, and ‘Independent Network Christianity’. And we are not only talking about charismatics as part of the evangelical mainstream. The Roman Catholic Church, which in the mid-1970s became perhaps the first mainline denomination to take engagement with charismatics seriously, has increasingly sought to integrate them into its larger life.

Age of the Spirit follows the movement of charismatic practices and experiences from the periphery to the mainstream. It shows, furthermore, how Anglo-world charismatic networks, and an imaginary of ‘charismatic renewal’ or a ‘New Pentecost’, were situated in, and increasingly connected with, a wider global context, through transnational flows of media, people and money,

For a religious studies scholar, a particular aspect of interest may be the tangled genealogies which produced charismatic renewal. The book discusses the influence, for example, of early century healing movements; not only sacramental and thaumaturgical, but as Pam Klassen’s (2011) work has also shown, metaphysical or experimental approaches to healing, for example in the New Thought tradition. Charismatic renewal often emerged from a seedbed of ‘seekership’, the kind which Steve Sutcliffe (2002) has identified as a context for the development of the New Age movement. For charismatics, authenticity was to be found in ‘going back to the beginning’ – a rediscovery of the power of the Holy Spirit in a nuclear age, and of the supernatural world of New Testament Christianity as everyday experience.

As the book claims, if you want to understand global Christianity, you need to engage with charismatics. I hope this research will go some way towards helping others to do so.

References:

Atherstone, Andrew. (2022). Repackaging Christianity: Alpha and the building of global brand. London: Hodder & Stoughton

Klassen, Pamela E. (2011). Spirits of Protestantism: Medicine, Healing, and Liberal Christianity. Oakland: University of California Press.

Maiden, John (2023). Age of the Spirit: Charismatic Renewal, the Anglo-World, and Global Christianity, 1945-1980. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sutcliffe, Steven. (2002). Children of the new age: A History of Spiritual Practices. London: Routledge.