I went to the funeral of some friends’ father a few months ago. John Ogden was a good person. He was a giant of a man in humaneness, intelligence, and capacity; loved by his family and friends; and a lover of Manchester City (everyone has their blind spots…). He had a unique sense of humour which would easily have held its own with stand-up comics. If you spent time with John, you laughed, almost cathartically. His absence is going to be felt deeply, and by many, amongst his family and in the Christian congregation he helped lead over decades.

John had been a leader in a church in Salford, northern England. The congregation was a Brethren assembly when John and his wife Gwyn joined in 1973. However, the church, like various other Brethren assemblies in places such as the UK, New Zealand (see Peter Lineham’s scholarly work) and Australia, became increasingly “charismatic” – as in emphasising the reality and power of the Holy Spirit – from the 1980s. There appears to be something about Brethren spirituality which seems to predispose a desire to seek the presence and embodied experience of God. John, with others, steered the congregation in a charismatic direction. In the 1990s, he and other leaders from Salford, and tens of thousands of others worldwide, visited a new global node for charismatic Christianity: the Toronto Airport Vineyard Church. It was said that here was a new ‘move’ or ‘blessing’ of the Spirit, a distinctive experience of God’s love.

The funeral included something I had never seen before. In 1960, John started to keep a reading diary. Every book he read, of whatever genre, was recorded. The long list of all these texts was placed on the wall of the chapel, for our interest.

His reading tastes – over 1,700 books – were eclectic. Indeed, even the first two books on the list offer quite the juxtaposition: Norman Vincent Peale’s The Power of Positive Thinking (1952) and A. J. P. Taylor’s The Hapsburg Monarchy: 1980-1918 (1941). The list revealed interests as wide-ranging as Christian theology and testimony, country music, military history, local Manchester and Salford history, the National Football League (NFL), Russian travel, and cricket. He covered impressive ground in modern novels. After retirement, in particular, he was a voracious reader. To see the list on display at the funeral was an insight into the interior life of a man – his intellectual and emotional formation – over many decades.

For a historian of Christianity, the list is a unique, rare source. For nearly a decade, I have been researching charismatic, or ‘Spirit-filled’, media and networks. What does the list tell us?

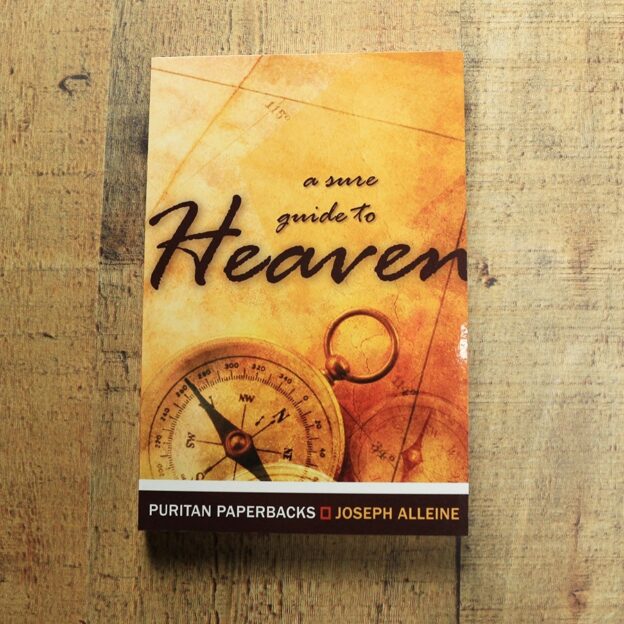

Certainly, it underlines it is all too easy to make straightforward assumptions about charismatic spirituality. John read, of course, classic charismatic and pentecostal texts. Indeed, from around 1987, like many other British Christians, he was devouring them: Dennis Bennett, Arthur Wallis, Derek Prince, Jamie Buckingham etc., all the luminaries of the charismatic renewal. But the list indicates also how textual influences on John’s spirituality varied and changed over time. From the 1990s, one of the most consistent spiritual influences in John’s reading life became the Puritan divines: Richard Sibbes, Thomas Goodwin, John Flavell, John Owen, and others. Indeed, outside of an academic theology department, you would struggle to find a Christian as well read in Puritan spirituality. (In the final months of John’s Life, he read the Puritans deeply, including, and movingly, Richard Sibbes Let Not Your Hearts Be Troubled, Joseph Alleine’s A Sure Guide to Heaven and William Perkins’ A Salve for a Sick Man). In the 1990s, also, John was turning to the medieval mystics, Teresa of Avilla, Julian of Norwich, and others. At the end of the decade, numerous works by contemporary Catholic twentieth century contemplative and devotional writers, such as the American Trappist Thomas Merton and Henri Nouwen, appear. Spiritual influences were broadening and deepening.

As a young undergraduate student in the late 1990s, I remember hearing John preach on the Old Testament book of Song of Songs. He read the text allegorically. The sermon was an articulate and heartfelt case for ‘spiritual union with Christ’. The congregation was at this stage impacted by the Toronto Airport Vineyard Church phenomenon, and I observed around me a collective eagerness to ‘soak’ in the love of God. John had visited Toronto: but who was John reading at this stage? The list reveals he was drawing on historic works on Song of Songs: the works of Madame Guyon and Bernard of Clairvoux and others. The jet-age meets medieval mysticism.

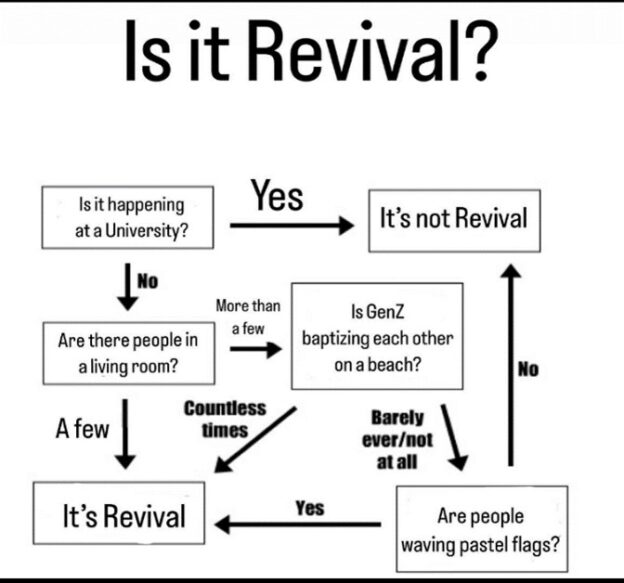

What might John’s reading list tell a historian of Christianity? First, it hints at the diverse and complex lineages – for example, contemplative, mystic, Reformed and pentecostal – which have contributed to charismatic spirituality. These influences, of course, have varied markedly across church traditions and between individuals. The story of these individual Christians – the ‘thick detail’ of ordinary leaders and laity, rather than the ‘big names’ of the charismatic world – are a rich mine of information for understanding ‘Spirit-filled’ movements in their everyday context. Second, to merely suggest that charismatics such as John were ‘revival-chasers’ (e.g. to Toronto), would be to overlook the significant, text-constructed, intellectual and experiential thought-world which could provide a spiritual framework, and which in John’s case was both consistent and extendable. Third, John’s patterns of devotion in reading point towards a much larger charismatic theme: of resourcement. While charismatic Christians will often emphasise the ‘new wine’ that God is offering – they are ‘presentist’ in this sense – they have, as John did in the 1990s, often referred to historic writings, the resources of the Christian tradition, the words of the Christian dead, to situate their experiences.

A meta-theme of John Ogden’s spirituality was the idea of the Christian as ‘beloved’ (indeed, he would, tongue-in-cheek, refer to himself as ‘the disciple who Jesus loved’). I suspect that through his reading, he became convinced that the ‘new thing’ of Toronto was an ‘old thing’ – a mystical experience of divine love within Christian spirituality.

Dr John Maiden is the author of Age of the Spirit: Charismatic Renewal, the Anglo-world and Global Christianity, 1945-1980 (forthcoming from Oxford University Press).