Introduction

In recent weeks, I have seen many social media posts saying something like “The conspiracy theorists were right”. As a scholar of conspiracy theories and religion, I am acutely aware of how the label “conspiracy theory” has historically been weaponised to dismiss legitimate scrutiny of the powerful. Yet even I was struck by the sheer scale of organised collusion among the global elite revealed in the unsealed Epstein documents.

There is absolutely no doubt that the unsealed files contain damning evidence of organised abuse, paedophilia, trafficking, torture, and more. But I’ve also seen many comments saying that Epstein and his circle were Satanists. Sometimes it’s being used as a metaphor to express a profound disgust, but comments like the one pictured above clearly mean it in a literal, religious sense. As a scholar working in this area for many years, I saw immediately that the claims found in a few files about rituals involving abuse, infanticide, cannibalism and worse, had a striking similarity to claims made during the Satanic Ritual Abuse panic of the 1980s and ‘90s. These parallels demand careful consideration, not to cast doubts on the whole collection of files, but rather to ensure that the strong empirical evidence they contain is not contaminated with unverifiable and fantastical claims.

The Satanic Ritual Abuse scare (SRA)

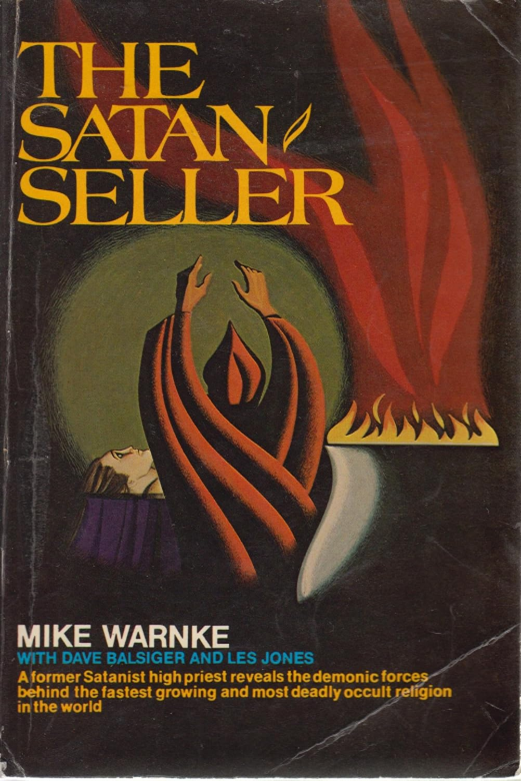

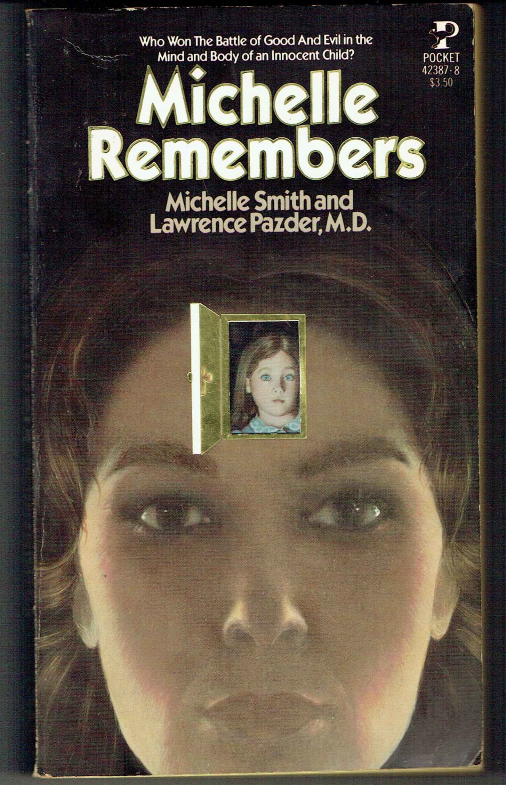

From the late 1960s, parents across the West became concerned about the ideas being espoused by their increasingly radical and rebellious children. Rock music, roleplaying games, marijuana, and an interest in Eastern and indigenous religions were framed not simply as moral threats but as an active attempt to indoctrinate children into the occult. In popular bestsellers like The Satan Seller and Michelle Remembers, this morphed into a terrifying narrative in which an vast global network of Satanic sleeper-cells was systematically abducting and abusing children as part of a plot to destroy civilisation.

By 1990, this narrative had achieved mainstream acceptance. Politicians, law enforcement, medical professionals, academics, and the press across the Western world treated the existence of this clandestine Satanic religion as fact. Some accounts numbered these Satanists in the millions, yet when they were tested in court, they failed to produce any empirical evidence. High-profile cases like McMartin Preschool trial (US), Christchurch (NZ), Orkney and Rochdale (UK) resulted in no lasting prosecutions and have been heavily criticised since. The labyrinthine tunnels under preschools, the bodies of countless murdered infants, and the physical evidence of the alleged abuse described by the prosecution were never found. The child witness testimony, often elicited through discredited techniques like hypnotic regression and coercive questioning, was later deemed fundamentally unreliable. Unlike what was heard in court, the childrens’ full testimony included many fantastical or dreamlike elements, such as adults flying or shape-shifting. Lynley Hood’s meticulous account of the Christchurch tragedy, A City Possessed, demonstrates conclusively how investigators’ pre-existing belief in a vast Satanic conspiracy, together with parents’ anxiety, led them to manufacture a crisis where none existed.

The simple, scholarly consensus is that the religion at the heart of the SRA panic does not, and never did, exist. Scholars of new religions and occultism consistently reject the claim. There are Satanists, but very few of them, and we know their histories, their texts and their practices. None of them advise any kind of abuse, ritual or otherwise. The majority don’t even literally “worship Satan”, but rather are atheists who see Satan as a symbol of the individual will and intellectual freedom. The Satanists of SRA and the Epstein files are rather part of the Christian imagination. SRA proponents erroneously present all of the occult, and often new religions too and even spirituality as Satanism. For them, Satanism is literally just negative Christianity—upside-down crosses, black robes for white, obscene sacraments. It is a projection of cultural fears onto an invented “Other”, so it stands to reason that their sacred rituals would involve the most profane acts imaginable.

This process of Othering has a long and ugly lineage. The same accusations of infanticide, cannibalism, and orgiastic rituals levelled at SRA practitioners were previously aimed at fourth-century Gnostics, medieval witches, and Jewish communities across Europe for centuries. These claims, and the language of vermin, and disease they typically employ, has a social function – by portraying the Other as less than human, we justify our dominance over them. Similarly, by portraying their crimes as supernatural in origin, we remove human agency from the equation, reframing it as part of a cosmic battle.

Although state-sponsored search for Satanists waned, the underlying narrative did not disappear. The Aberdeen journalist Robert Green has been investigating the claims of Hollie Greig, a teenager with Down’s Syndrome, since 2000. In Hampstead in 2014, there were public protests outside a local church after a man coached his children to make ritual abuse claims against his ex-partner in a failed attempt to gain custody. Several newspapers reported claims that Jimmy Savile was involved in Satanism (see below), and Operation Midland (2014-2016), accused several prominent political figures of involvement in a paedophile ring in Parliament. It collapsed after an enquiry showed that the key witness, Carl Beech, was a serial fantasist and convicted child abuser. In 2016, Pizzagate (a forerunner of QAnon) attempted to “decode” emails from Democrat politicians to reveal paedophilic and cannibalistic messages. Yet at the same time, Jeffrey Epstein, Prince Andrew, Donald Trump and any number of Bishops seemed time and again to avoid investigation.

SRA in Epstein Files

We need to bear this historical context in mind while considering the claims in the Epstein files. The most widely-circulated document is a 2019 FBI report of an interview with a man claiming to be an Epstein victim. The man claimed, amongst other things, that his whole family was part of the abuse ring, that he was raped by Epstein, George Bush Sr. and Bill Clinton while Trump watched, that his feet were ritualistically cut with a scimitar, and that he saw babies being dismembered, disembowelled, and the attendees eating the faeces. What is often omitted from these discussions is the investigating detective’s own prefatory email, which points out a number of familiar reasons not to pursue the claims further—the claims were “repressed memories” obtained through hypnotic therapy, there was no supporting evidence or witness proffered, the witness appeared emotionally unbalanced, and was encouraged to come forward by a person known to promote SRA claims. I would add that the incongruous detail about the scimitar is a clear example of the fantastical and dreamlike nature of these accounts.

Another document, since withdrawn, has Trump present as babies are killed, and girls being strangled in full view of guests and buried under the golf course in Mar-A-Lago. It is worth noting however that these supposedly took place at parties, not in religious rituals. And while there are around fifty mentions of “cannibal” or “cannibalism” among the three million files, none of them are allegations that it happened. That doesn’t stop posters like the one below from extrapolating it from earlier (equally flimsy) accusations however.