Who is given the authority to theorise?

The voices of Indigenous people, especially women, have been excluded and nearly absent until early- to mid-twentieth-century sources. Although Indigenous women often contributed to the research of visiting ethnographers and anthropologists, especially with translation, their work has almost never been acknowledged or credited. Women were routinely depicted in relation to their men and were mostly mentioned in sections about family, marriage practices, and traditional clothing. In the study of religion, scholars predominantly focused on Indigenous men’s practices since the observers were typically white men. Thus, Indigenous women’s knowledge production was not taken seriously until they themselves entered academic corridors of power.

A recent methodological turn in humanities caused by the emergence of Indigenous and decolonial studies had a major impact on the disciplines of ethnography, anthropology, and religious studies. Suddenly, ‘the objects of study’ could not only speak back but theorise back. As a result, the normative was de-normalised, universals particularised, and the methodological apparatus of academia destabilised. Theory-making is the most powerful academic endeavour, which has been historically dominated by Eurocentric male scholars. Within the last few decades, Indigenous women pushed themselves away from the position of the objectified and silenced others to leading intellectual resistance against colonial systems of knowledge.

While colonial ethnographers and anthropologists were preoccupied with describing exotic others and imposing Western notions of religion, race, culture, and gender, Indigenous women discussed the limits and impact of such approaches. Theorising from the ongoing experiences of coloniality, racism, and gender-based violence, Indigenous women continue to create and claim a place for themselves and for other marginalised voices within academia.

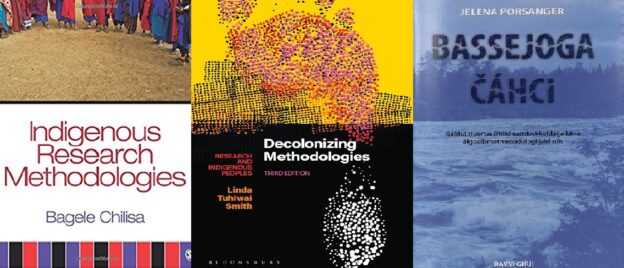

Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s groundbreaking volume Decolonising Methodologies (1999) was fundamental in the development of Indigenous research, Indigenous standpoint theory, whiteness studies, trauma theory, as well as decolonising work, and Indigenous knowledges approach. By theorising her experiences of encountering colonising knowledges from Māori perspectives, Tuhiwai Smith (1999: 10) pushes her readers to ask:

Whose research is this?

Who owns it?

Whose interests does it serve?

Who will benefit from it?

Who has designed its questions and framed its scope?

Who will carry it out?

Who will write it up?

How will the results be disseminated?[1]

We could further add:

Who is assumed to be a scholar?

Whose knowledges hold positional superiority?

Another pathbreaking contribution to Indigenous studies was made by Bagele Chilisa, in her Indigenous Research Methodologies (2012, 2019), where she proposes a research paradigm that aims to make knowledge systems of Indigenous peoples intelligible for academic research. While the first edition (2012) covers Indigenous methods, methodologies, and epistemologies informed by Bantu experiences and knowledges in an accessible and practical handbook, her second edition (2019) expands its focus to the use of mixed methods to incorporate even more effectively Indigenous knowledge productions.

So, despite the fact that Indigenous women were only able to enter academia a few decades ago, their voices are already at the forefront of theory-making with critical contributions from and within their localised contexts. One such pioneering example was set by Jelena Porsanger, who argued that theorising has historically been evaluated on the premises of Western academic knowledge and epistemology. Porsanger (2006, 2010) focuses her research on designing Sámi methodology based on Sámi epistemology and became the first scholar in Norway to defend her dissertation (on Sámi Indigenous religion) in Sámi language.

There are many more examples of Indigenous women in theory-making, especially with the recent rise of scholarship on human and other-than-human relations, which extensively draws on Indigenous systems of kinship and relations. Kim TallBear’s research on Indigenous (Cheyenne and Arapaho) ways of relating to land, water, and other-than-human entities is as urgent as never before. Kim TallBear’s (2017, 2019) contribution to the analysis of the historical and ongoing roles of science and technology (technoscience) in the colonisation of Indigenous people and others is just as formative as her research on colonial disruptions to Indigenous sexual and kin relations to Indigenous queer theory and (de)colonial sexualities.

The field of Indigenous studies has always been strongly dominated by Indigenous women, whose research continues to expand beyond the limits of academia and pushes for more innovative and inclusive theory-making. Indigenous women’s theoretical and methodological contributions are especially relevant to the study of religion, in which Indigenous knowledges have been historically reduced by Eurocentric scholars to ‘primitive religions,’ ‘shamanism,’ and ‘totemism’.

References:

Tuhiwai Smith, Linda. (1999). Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. New York: Zed Books.

Chilisa, Bagele. (2012, 2019). Indigenous Research Methodologies. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Porsanger, Jelena. (2006). Bassejoga čáhci. Gáldut nuortasámiid eamioskkoldaga birra álgoálbmotmetodologiijaid olis. University of Tromsø, Faculty of Humanities, Social Sciences and Education.

Porsanger, Jelena. (2010). Self-determination and indigenous research: capacity building on our own terms. Tauli-Corpuz V, Enkiwe-Abayao L, de Chavez R, Guillao JA (eds.) Towards an alternative development paradigm: indigenous peoples’ self- determined development. Tebtebba Foundation: Indigenous Peoples’ International Centre for Policy Research and Education/Valley Printing Specialist, Baguio City, pp. 433–446.

TallBear, K. (2017). “Beyond the Life/Not Life Binary: A Feminist-Indigenous Reading of Cryopreservation, Interspecies Thinking and the New Materialisms.” In Joanna Radin and Emma Kowal, eds., Cryopolitics: Frozen Life in a Melting World. Cambridge: MIT Press.

TallBear, K. (2019). Feminist, Queer, and Indigenous Thinking as an Antidote to Masculinist Objectivity and Binary Thinking in Biological Anthropology. American Anthropologist, 121(2), 494–496.

[1] The legacy of this monument of a book was celebrated by the Bloomsbury collection Indigenous Women’s Voices: 20 Years on from Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s Decolonizing Methodologies (2022).