In the 2021 census, ‘No religion’ was the second most common response (37.2% or 22.2 million people), while ‘for the first time in a census of England and Wales, less than half of the population (46.2%, 27.5 million people) described themselves as “Christian”’.

These statistics relating to people who self-identify as being of No Religion—also known as Nones—have been receiving media attention, and Hannah Waite has produced a fascinating report The Nones: Who are they and what do they believe? (Theos, 2022). Waite concludes that there are broadly ‘three distinctive types or clusters of Nones’:

“Campaigning Nones” are self-consciously atheistic and hostile to religion; “Tolerant Nones” are broadly atheistic but accepting of (sometimes warm towards) religion; and “Spiritual Nones”, who are characterised by a range of spiritual beliefs and practices, as much as many people who tick the “Religion” box (Waite 2022, 6).

In the course of the ‘Pilgrimage and England’s Cathedrals Past and Present’ research project, we discovered that people who self-identify as being of No Religion, the Nones, appear to be regularly visiting cathedrals in England today. What are they doing there? And what does this tell us about the internal diversity of this growing demographic?

The 3-year interdisciplinary AHRC-funded project, ‘Pilgrimage and England’s Cathedrals, past and present’ (pilgrimageandcathedrals.ac.uk) involved partnership with Canterbury Cathedral, Durham Cathedral and York Minster (all now Anglican, Church of England), and Westminster Cathedral (Roman Catholic). The genesis of the project was the fact that both pilgrimage and engaging with cathedrals now appear to be more popular in England than at any point since the Reformation. This popular mapping of meaning onto special places and interest in pilgrimage gives rise to questions such as: ‘Why is this happening now?’, ‘What is going on?’ and, significantly for our purposes here, ‘Who is involved?’.

For the contemporary data collection, we employed both qualitative and quantitative methodologies. Altogether, we conducted 110 face-to-face interviews and 25 email interviews, and received 500 completed paper questionnaires and 58 online questionnaire responses. We also employed participant observation, and ‘hanging out’ which included sitting in different parts of a cathedral at different times of day and simply people-watching. This allowed different forms of data to be linked together. For example, an activity that shows up in statistics like candle lighting could be followed up by talking to the volunteer who cleans the candle stand, the visitor who lights the candle, but also by simply observing a candle stand over time, without intervening, just to see how often candles are lit, what might be done in relation to candle lighting, where the most popular spaces to light a candle might be, and so on. I’m going to concentrate here on findings from our three Anglican cathedrals— Canterbury Cathedral (one of England’s preeminent medieval pilgrimage destinations), York Minster (one of the largest medieval Gothic cathedrals in Northern Europe) and Durham Cathedral.

Site of Shrine of Thomas Becket, Canterbury Cathedral (Photograph Marion Bowman)

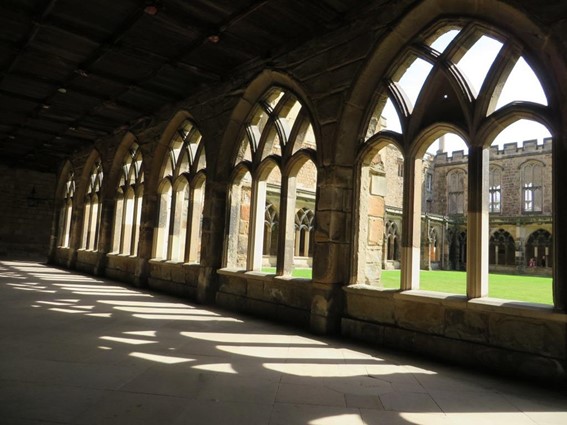

York Minster (Photograph Marion Bowman)

St Cuthbert’s Shrine, Durham Cathedral (Photograph Marion Bowman)

The current popularity of cathedrals like these has taken many by surprise. Grace Davie comments that, as late as the 1970s, ‘these iconic buildings were frequently referred to as dinosaurs, large and useless’ (2012, 486). However, since the mid-1990’s visitor numbers and numbers attending Cathedral services have grown substantially, and the most popular cathedrals have been those that are both medieval and larger in scale—like Durham, York and Canterbury.

There has been a gradual recognition that cathedrals are seen by a great range of people, including Nones, as different and significant spaces. In 2012, over a quarter (27%) of England’s adult population stated that they had been to a Church of England cathedral within the previous 12 months. However, the people who visit cathedrals are very varied. As the Theos Report Spiritual Capital: The Present and Future of English Cathedrals put it,

Because…the established Church, has long been (understood as) an institution with clear and confirmed views on spiritual issues, it does not naturally inhabit the more liminal spiritual space that ever more people are occupying. While not necessarily unique in their position, cathedrals are an important exception to this—clearly and distinctly perceived as Christian, and as institutions, but at the same time understood as open spaces of spiritual possibility [italics and bold in the original] in which exploration and development of emergent spiritualities are made possible (2012, 55).

Undoubtedly this is part of the broader trend towards ‘heritagization’, whereby material culture, places and praxis from the past are made, or presented as, meaningful in the present. While the ‘heritagization of religion’ may well be instrumental in the broadening appeal of cathedrals, arguably the ‘spiritualization of heritage’ is at work here also. The presentation of cathedrals as heritage, open and meaningful to all, regardless of religious or spiritual affiliation, seems to be taken a stage further by many visitors who find these heritagised buildings inherently ‘spiritual’ in a non-aligned or supra-confessional way (Bowman and Sepp, 2019; Coleman and Bowman, 2019).

Some interesting observations emerged from our fieldwork and interviews in relation to what sort of spaces cathedrals are, and how they can relate to the broader social, spiritual and secular milieu. Cathedrals are multivalent spaces, spaces with many different meanings, and what people do, or find, or encounter or expect within them can be endlessly varied and complex. On any given day, cathedrals, which tend to see themselves primarily as working churches, may play host to hundreds of unpredictable visitors, with varying degrees of religious literacy, and with a range of expectations and agendas in relation to how they regard these places and want to interact with them.

Cathedrals are also spaces of ‘relationality’. That relationality or connectivity, for many visitors to cathedrals, as well as staff and volunteers, might now be not so much with saints but with the building itself, and through its multivalent spaces connections with the past; with local, regional or national history; with family and personal biography; with the people of faith who have prayed there over the centuries (even if that faith was very different from the worldview of contemporary visitors); or simply with a more generalised sense of sacredness, holiness, or specialness.

In ‘Possibility and Diversity in Urban Life,’ the geographers Karen Franck and Quentin Stevens (2007) talk of how cities are composed of a great variety of place types. What they call tighter, more constraining types include office towers or libraries, where behavioural norms are coercive, and surveillance is evident. But they also note that much public space and civic space involves expectations that are less exclusive and more fluid and they refer to what they call ‘loose space’. We realised that the categories of looseness and tightness could apply not just to cities but could also express well the tensions, ambiguities, and above all opportunities that manifest around and within cathedrals as spaces with multiple frames and multiple claims.

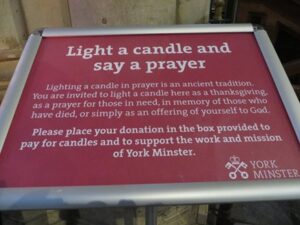

Sometimes, activity in a cathedral is highly focused and regulated in space and time, as during a service. However, some spaces and activities are far less regulated and focused (e.g. the ‘empty’ spaces of the nave where one can sit undisturbed, the cloisters, the cathedral shop) and we came to appreciate that the idea of looseness is a considerable part of the attraction of cathedrals. Furthermore, this looseness works well for certain types of Nones. In addition to tight and loose spaces, we might also think in terms of loose activities—candle lighting being an excellent example of this. Key to the candle’s multivalence (its ability to produce and express multiple meanings) and its ambivalence (the fact that we can never be entirely sure what is going on when a candle is lit) is that candle lighting can be performed with or without precise articulation of what is being done. Lighting a candle can be intensely meaningful, whether or not that meaning is or can be expressed, and in many ways this really suits the cathedral context with a broad spectrum of visitors.

Sign about candle lighting, York Minster

Candle stand, Durham Cathedral

One long-serving guide at Durham Cathedral told us in relation to people lighting candles: ‘I’m really astonished that people will come… and I’m there, stewarding for a service… and quite often somebody will say, can I just go and light a candle? They’re not wanting to come to the service, they just want to light a candle, and the candle does something for them.’

Questionnaire responses from our Anglican cathedrals revealed some interesting data in relation to ‘Nones’. Depending on the cathedral context, between a third and a half offered ‘no religion’ as affiliation in our surveys, slightly outnumbering those who described themselves as Anglican or Catholic. And here there’s a confession to make: we probably shot ourselves in the foot a bit by how we worded one of the demographic questions, ‘Please indicate any religious affiliation’. The fact that this question got an uncharacteristically high ‘no response’ level could well indicate that this question was simply ignored or passed over by many without any religious affiliation so that should be taken into account when you see the graph below.

Naturally we wanted to get an idea of what people were doing in the cathedrals, and we were trying to challenge the idea that some cathedral staff and volunteers seemed to have that people were either Christians and potential worshippers or ‘just visitors’ with no interest in the religious or spiritual side of the cathedral.

‘No religion’ often means no institutional religious affiliation, but does not necessarily mean not religious or spiritually inclined. We found that the self-identified Nones who responded to our questionnaires were not only taking guided tours of the Cathedral or reading guidebooks, but also lighting candles and praying.

From some of the responses for ‘Other’ among the Nones, we can see that the cathedrals were offering not simply the context for appreciation of architecture and aesthetic pursuits, but providing meaningful spaces for quiet reflection, meditation, remembrance of the dead, as well as candle lighting and prayer. Examples included ‘Thought about my life; the significance of other people’s contribution’; ‘Sat to reflect on those most dear to me, dead and alive’; ‘Meditated’; ‘Spoke to someone about the meaning of life’.

For some Nones, those who are outside institutional religion but not entirely ‘secular’, it appears that cathedrals, presented as heritage—open and meaningful to all, regardless of religious affiliation—can be ‘spiritual’ in a non-aligned or supra-confessional way. The cathedrals can act as comfortable open spaces of spiritual possibility.

Just as we are finding Nones in the cathedral, Nones are also frequently to be found on routes with roots, part of the trend of new pilgrimage where heritagised, linear loose spaces afford opportunities to feel part of a spiritual tradition though removed from doctrinal constraints or expectations (see Bowman, Johannsen and Ohrvik, 2020). The convergence of these trends was neatly summed up for me in communication with a pilgrimage service provider in Canterbury:

The secret may lie in the fact that while many people no longer take part in organised religion, they still recognise a spiritual dimension to their lives. They don’t want the commitment or the formality of going to church but are happy to pop into a cathedral or say a quick prayer. A pilgrimage is the perfect opportunity for this sort of informal spirituality.

Nones are a variegated demographic, ranging from militant atheist, through humanist, to agnostic to extra-institutional spiritual seeker and spiritual experiencer. Perhaps the Nones we encountered would, in Waite’s terminology, be characterised as ‘Tolerant Nones’ and ‘Spiritual Nones’. It does seem that when we are thinking about what Nones ‘do’ and where Nones are to be found, cathedrals and pilgrimage are fruitful loci for research. Based on our research, it certainly seems that at least some of those who self-identify as being of No Religion appear to be comfortable doing a variety of things and having varied experiences in cathedrals in England today.

References

Bowman, Marion and Sepp, Tiina. 2019. ‘Caminoisation and Cathedrals: replication, the heritagisation of religion, and the spiritualisation of heritage’. Religion 49 (1): 74–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/0048721X.2018.1515325

Bowman, Marion, Dirk Johannsen and Ane Ohrvik. 2020. ‘Reframing Pilgrimage in Northern Europe. Introduction to the Special Issue’. Numen 67 (5-6): 439-452. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685276-12341597

Coleman, Simon and Bowman, Marion. 2019. ‘Religion in cathedrals: pilgrimage, heritage, adjacency, and the politics of replication in Northern Europe’, Introduction to co-edited, themed issue of Religion 49 (1): 1-23 https://doi.org/10.1080/0048721X.2018.1515341

Davie, Grace. 2012. “A Short Afterword: Thinking Spatially About Religion.” Culture and Religion 13: 485-489. https://doi.org/10.1080/14755610.2012.728387