By Hugh Beattie

Commentators sometimes give the impression that the Taliban, who ruled Afghanistan from the mid-1990s until 2001 and have recently taken over the country again, represent traditional Afghan Islam. Of course there are continuities with the past, but the Taliban are a modern phenomenon. Among the main reasons for their emergence are British rule in India followed by its partition and the creation of Pakistan, as well as the cold war, and the support from the West and Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf states for the anti-Soviet jihad during the 1980s. The idea that their aim is to return the country to a medieval past is an oversimplification for a number of reasons. Here we look at two in particular, their interpretation of Islam and their political role.

Just a little background first. Afghans are almost entirely Muslim, though Hindus and Sikhs still live in the cities. There were once small Jewish and Armenian communities too, and Ahmadiyyas, inspired by the controversial Muslim modernist and reformer Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835-1908), also made some converts. The Muslims are mostly Sunni, but there are some significant Shi‘a communities, both Imami (the dominant strand in Iran) and Nizari Ismaili (who follow the Aga Khan). There are other Shi‘a communities in Afghanistan, but the majority of those practising Imami Shi‘ism are Hazaras, belonging to an ethnic group whose homeland is in central Afghanistan (though many now live in Kabul and in Quetta across the border in Pakistan). Afghan Ismailis mostly live in Badakhshan in the north-east. As in other parts of the Muslim-majority world, there have often been tensions between Sunnis and Shi‘as, particularly the Hazaras. Recently the Taliban destroyed a statue in Bamiyan, a valley in central Afghanistan with a largely Hazara population, to commemorate a Hazara Shi‘a political leader Abdul Ali Mazari, killed by the Taliban in 1995. Bamiyan was known for its two huge statues of the Buddha carved into a cliff face, which were largely destroyed by the Taliban in 2000. A Hazara boy is also the ‘kite-runner’ of the novel of the same name by Khaled Hosseini.

Traditional Afghan Islam was very different from the Islam of today’s Taliban – let along ISIS-K, which has gained a foothold in eastern Afghanistan since 2014 (K for Khorasan, a province of the ancient Iranian Sassanian empire which comprised eastern Iran and much of Afghanistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan). In particular traditional Afghan Islam combined law and ethics (shari‘a) with Sufi teaching and practice. This Afghan Islam, the scholar Bashir Ahmad Ansari, argues, ‘encouraged peaceful life with justice, compassion, and tolerance among the largely illiterate peoples of the region before the 1970s’ (Ansari 2018, p.37).

Tiles from the shrine of the Khorasani Sufi poet and scholar Abdullah Ansari (d.1089 CE) in Herat in western Afghanistan | https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/en/reports/context-culture/a-sufi-lodge-a-leaning-minaret-and-a-polymaths-shrine-a-look-at-recent-efforts-to-preserve-and-appreciate-historical-herat/

An important feature of this Afghan Islam, as with popular Islam throughout most of the Muslim-majority world, was the way that Sufi masters were believed to possess miraculous powers and their tombs became places of pilgrimage, shrines (ziyarats) that were visited, particularly by women, in the hope that this would bring healing, good fortune in general, and ultimately salvation. These shrines have played a very important role for hundreds of years; some were located at important pre-Islamic religious locations, and sometimes the practices associated with them incorporated extra-Islamic elements.

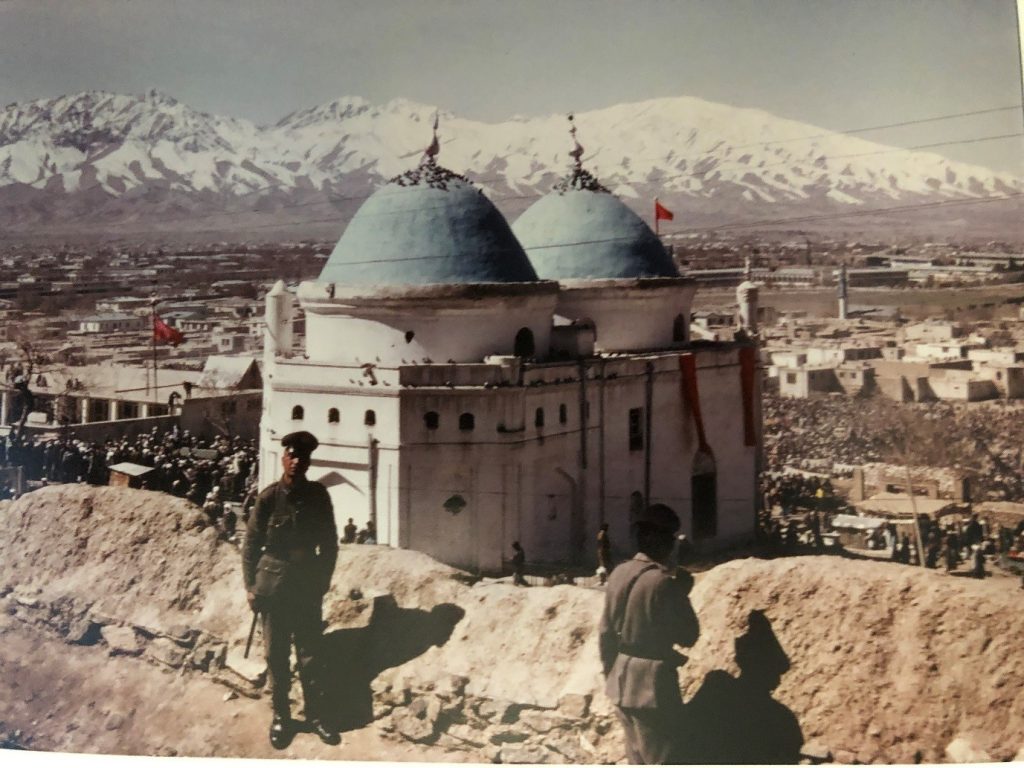

A good example of this is the annual ritual of raising a 75 foot high iron pole wrapped in green silk, with colourful scarves attached around the top (known as janda bala kardan), at the supposed tomb of the fourth caliph, Ali, in the Blue Mosque in the city of Mazar-i-Sharif in northern Afghanistan. This still takes place on Nowruz, New Year’s Day according to the solar Hijri calendar (March 21), and is always a joyful occasion, a kind of spring festival. Similar rituals on a smaller scale used to take place at a number of other shrines in northern Afghanistan, and in Kabul itself. In the image at the beginning of this article, taken in 2012, we see the standard about to be raised.

The ritual is attended by both Sunni and Shi’a pilgrims. Ansari’s characterisation of traditional Afghan Islam may be a somewhat idealised one, but there is no doubt that it was very different from the Islam of the Taliban and ISIS-K. Both are opposed to the practices associated with shrines (known as ziyarats) because they see them as non-Muslim in origin, and argue that prayers to Sufi ‘saints’ (pirs) for healing and intercession are sinful because they implicitly deny the oneness of God. During the earlier period of Taliban rule it seems that they often banned Sufi meetings (see e.g. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-south-asia-12539409).

A second difference between traditional Islam in Afghanistan and the Islam of the Taliban and ISIS-K is the extent to which the latter groups have taken a political role. In the past, Sufi saints were sometimes able to use the authority that belief in their spiritual power (karamat) gave them to acquire political influence, and their descendants sometimes inherited this. An important example in Afghanistan has been the Mujaddidi family (linked with the Naqshbandi Sufi tradition). Mujaddidis moved to Afghanistan from India during the 18th century and became very influential, even claiming the hereditary right to crown Afghan rulers at their coronations. The Gailanis, linked with the Qadiriyya Sufi order, are another influential family with inherited religious charisma. But figures like these rarely if ever actually ruled the country.

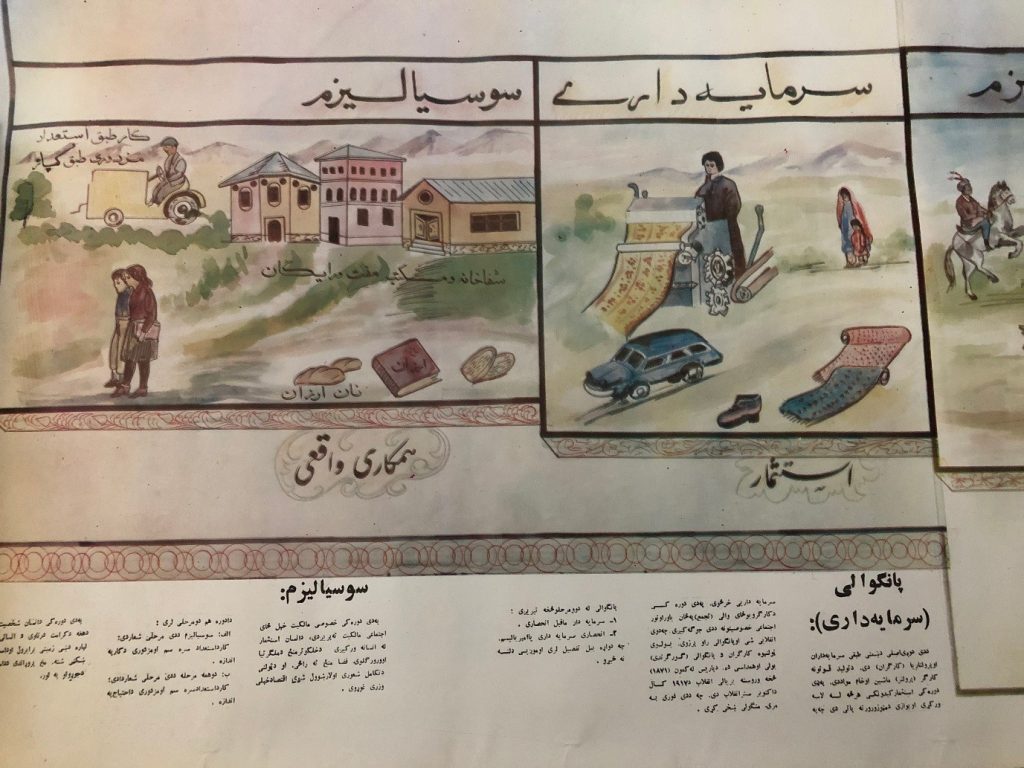

Since the late 1970s, however, the political importance of religion and men with a religious training has grown. The Taliban themselves mostly belong to the revivalist Deobandi tradition, which developed from an influential seminary (madrasah) found in northern India in 1867. Its founders were determined to resist the modernizing and secularizing pressures that accompanied British rule in India. This was to be achieved by working to ensure that Muslims would continue to live as far as possible according to Islamic principles and Islamic law. After the British withdrawal from India in 1947, Deobandis began to set up seminaries in the new state of Pakistan. During the Afghan jihad in the 1980s they set up many more along the frontier with Afghanistan which were attended by young Afghan male refugees fleeing the Soviet occupation that had begun in 1979. It was and remains these men, led by graduates of seminaries (mullahs), mostly lacking Sufi connections, who are the core of the Taliban.

Taliban rule, therefore, was not and is not simply a return to traditional Islam in Afghanistan. Since Afghanistan became predominantly Muslim, rulers have always proclaimed their support for Islam, but government by men claiming that their religious training and mission entitle them to take control of the country is something new.