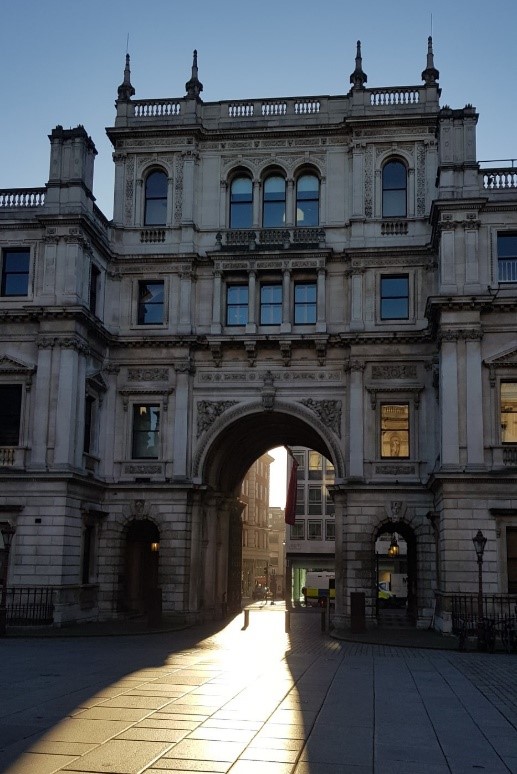

On the 17-18th January this year, academics, activists, journalists, religious, policy makers and artists assembled at Burlington House in London (see photograph) for a series of trans-disciplinary talks and activities to address the role of religious institutions and religious communities both in the generation and dissemination of disinformation but also in the cultivation of information literacy to resist information manipulation. The event was organised by Dr Paul-François Tremlett (Religious Studies) and Dr Precious Chatterje-Doody (POLIS) and was funded by the Open Societal Challenges initiative at the Open University (see Democracy, Information, and the cultural capital of Religion: Sharing Global Best Practice on Press and Election Manipulation (open.ac.uk)). Their respective expertise in the Philippines and Russia – countries where powerful religious institutions have promoted disinformational and anti-disinformational narratives – was the catalyst for the event, which sought to analyse shifting and multi-layered contexts including a neoliberal frame that pervades contemporary economic and political discourses where the financialization of everything means big profits for those creating and dissemating disinformation, huge dissatisfaction with ruling elites across the global South and global North accompanied by a rise in populist and divisive politics, and widespread disengagement from traditional forms of political participation as governments appear increasingly distant from and unresponsive to the populations they are supposed to serve.

In such fractious times disinformation, conspiracy theories and dissension can feel like the means to “stick it to the man”. Indeed, they offer forms of political and discursive participation albeit ones grounded in a constellation of affects from anger to vexatiousness (among others) that signal a breakdown of trust in once hallowed and taken-for-granted institutions, political and cultural traditions and social memories. Bringing religion – often a synecdoche for stability, morality, tradition and trust – into the conversation about democracy and disinformation, means that we can start to explore the involvement of religious institutions and communities in spreading and/or contesting disinformational narratives, but also work to refine our theoretical and methodological tools to study the entanglements of the information and disinformation-scapes of religion and democracy.

When it comes to information, of course, there is no passage to a neutral language or medium that can be detached from politics, history or passion or indeed from situated reception and interpretation. We know that what we’re talking about is power; networks of alliances and forces which the political strategist Antonio Gramsci, in the Prison Notebooks, characterised as “unstable equilibria”. Solving the problems around democracy, information, election manipulation and religion cannot be done by fact-checking or media, political and religious literacy training alone, as much as such initiatives help. Rather, the interventions we design must make the most of those “unstable equilibria” to find new centres of gravity around the commons and the public good. We’re hopeful that through our event and the interactions and collaborations it has set in motion, we will develop new initiatives to tackle what’s rapidly emerging as a key challenge of our time.