I lived in Leith when my kids were small, so I spent a lot of time pushing a pram around. I got to know the streets and paths well, and the many interesting buildings. Although more famous today for the poverty and addiction that plagued the area in the 1980s and 1990s, Leith was a hugely wealthy harbour for most of its long existence, and the evidence is written in the dark sandstone.

Figure 1 – The Green Man, Junction Street, Leith (photo by the author)

Something I quickly noticed was the many example of the “Green Man” around the place. Like many (including the King!), I’ve long been fascinated with the verdant, vigorous, vital trickster grinning down from the eaves. He seems to speak of a pagan past – even though in fact he was a Victorian invention that synthesised a number of different local figures and traditions into a single universal figure, in much the same way that today’s Wheel of the Year — the pagan calendar of equinoxes, solstices and “quarter days” — was created. He fitted the growth of interest in “folk customs” that accompanied urbanisation, and the fashion for ornate neo-gothic architecture, and so we should not be surprised that the wealthy merchants of Leith included him in their new buildings.

Figure 2 – Carved pair of heads, Constitution Street, Leith (photos by the author)

But then I noticed that in Leith, he often has a friend. I found several pairs of heads, matching except for their paraphernalia — where the Green Man seemed to be peering out from the greenery, leaves and vines and fruit in his hair, his friend had waves for a beard and shells in his hair.

Figure 3 – The Green Man, Junction Street, Leith (photo by the author)

I reached out to a local historian I know on Twitter, who told me that, in fact, most of the heads are meant to represent Bacchus (Greek god of wine), because alcohol was their primary import. This is very clear in the spectacular carving on the corner of Maritime Street, the former offices of “distillers, blenders and manufacturers of cordials”, Robertson, Sanderson & Company, which is replete with vines and bunches of grapes (as well as Scottish thistles).

Figure 4 – Bacchus head, Maritime Lane, Leith (photo by the author).

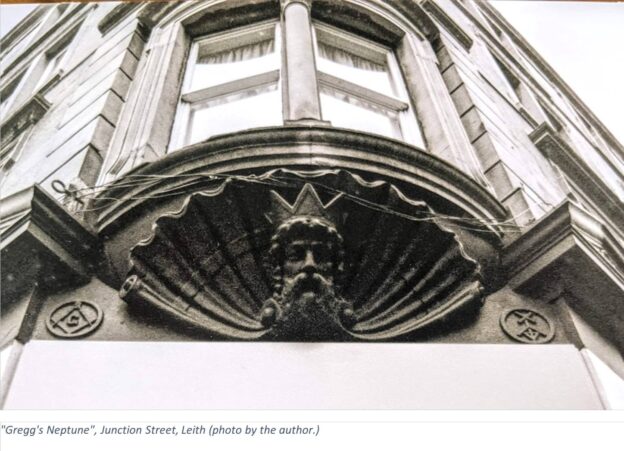

Where there are two heads, then, the second one represents Neptune, god of the sea – entirely fitting for a port. Pillars House was built by Pattison’s Whisky in the 19th century. (Pattinson’s were known for lavish spending, and they went bankrupt after caused a market crash). And on Commercial Street, the two heads appear on what was then the meeting room of the Leith Merchants’ Club. And then I found this one above the door of the Junction Street Gregg’s (although to judge by the other symbols, it must have been a Masonic Lodge when it was put up).

Figure 5. “Gregg’s Neptune”, Junction Street, Leith (photo by the author.)

This reminded me of Leonard Primiano’s principle that “all religion is vernacular”. While we have tended to think of there being five or six big, discrete and coherent religions, but when we look closely, it’s local variation all the way down. The presence of images of foreign gods in the streets of 21st century Scotland only makes sense when taking local economic factors into account.

But this should also make us reconsider these factors when we see “religious” imagery in other contexts too. While religion is clearly involved in the dedication of a temple to Jupiter or Siva, we should consider that the economics are also significant, and the presence of religious imagery doesn’t necessarily indicate devotion. A Trobriander islander might paint their canoe for religious reasons – but equally, they might be gaining a social or business advantage, or even merely decorative. We don’t, for example, generally interpret a Scottish or English flag painted on a truck or boat as indicating devotion, even though it is certainly a religious symbol.

I don’t live in Leith anymore, and my kids are both teenagers. But I still look up whenever I visit a new place, to see what gods might be up there.