Marjan Ajevski, Research Fellow in Law

In early July, 22 countries, all from the West, sent a letter to the UN Commission on Human Rights condemning the treatment of the Uyghur minority at the hands of the Chinese government. They raised serious concern regarding China’s arbitrary imprisonment of as many as 1 million Uyghurs in what China calls re-education camps under the guise of combating extremism. A few days later, a letter released by 37 UN ambassadors defended China’s treatment of the Uyghur minorities. They commended China’s human rights record and excused China’s treatment of the Uyghurs, noting that terrorism and extremism has caused enormous damage to the region where Uyghurs live. This polite exchange of diplomatic language over the backs of a million interned Uyghurs is a microcosm of the dilemma that liberal democracies are facing in the current international system. Let me explain.

World Flag Map; Author: Mason Vank (CC, Attribution, ShareAlike)

In its classical account, the international system is a system of anarchy, having no central authority, including a central lawmaker. It is predicated on the assumption that equal and independent states create and implement legal norms and that International law regulates the relationship between states or groups of states. Hence the states create, interpret and apply international law at the same time. A classical map of the world would like like the picture above, populated with states that have clear(ish) borders between inside/outside.

In this account, international norms must be connected to the consent of the state in some manner for them to be valid norms: treaties are negotiated, signed and ratified by states, custom is consistent state practice back up by opinio juris – the belief that the practice reflects a legal requirement; general principles are legal principles found in the legal systems of most states. Moreover, it is not only that consent is needed for an international norm to be opposable to a state, when consent is absent, international law accommodates the non-consenting state. For example, a state cannot be deemed to be obligated by a treaty that it is not a party to, and, under the persistent objector rule, a state that consistently and clearly objects to the emergence of a new custom, can be exempt from that custom. Unfortunately, this account of how international law works is no longer valid.

Since the end of WWII, there have been two streams of thought pushing to shape the international system. One is the reactionary force, trying to bring to life or preserve the relevance of the classical account. The other is the force that can best be described as the reform movement, an intellectual and political force, present since the beginning of the international legal profession, that tries to improve the position of individuals through the international system. The movement (not really an organization but more of a mood, a way of thinking) not only created and developed mature branches of substantive law, like international human rights and international criminal law, but also changed the way that international law was created and implemented. By the end of the 20th Century, we were starting to talk about a system of global governance, but without a government.

Global Air and Sea Routes by Dominic Alves (CC BY 2.0))

The global governance system is not a simple system to pin down. It’s a system that allows for (hard and soft) norms created at the international level to pierce the bubble of sovereignty and be implemented without the traditional constitutional gatekeeping mechanisms to be triggered. States are no longer the only ones that are involved in creating these norms, non-state actors, primarily international organizations, but NGO’s and multinational companies also participate in this norm-making. In addition, rather than operating as solid billiard balls, states are better seen in a disaggregated manner, where the different levels of government (both vertical and horizontal) can directly connect with levels in other jurisdictions, including the international level, therefore piercing the veil of sovereignty.

This system has created clear benefits, after all we are the richest, healthiest, oldest and most interconnected generation in the history of humanity. Moreover, if we are to tackle global challenges, like climate change, we need effective global institutions and mechanisms for cooperation. Nevertheless, this system created a problem for well-functioning and emerging liberal democracies – their internal constitutional arrangements that were predicated on a system of separation of powers, and some form of checks and balances, suddenly found itself out of balance in favour of the executive, but other non-state actors as well (think giant multinational companies).

For the past decade we have been debating how to reform the international system so as to remedy the problems for well-functioning liberal democracies. I’ve written previously why I think these debates didn’t produce the desired result, but to make a long story short, I argued the debate took for granted that projecting democratic governance internationally was the generally accepted attitude and therefore, did not build a case for international democratic governance. We were having a debate about how to reform world governance, without establishing a case for why, other than it is what liberal democracies need in order to return balance their domestic constitutional orders. It was presented as fait accompli.

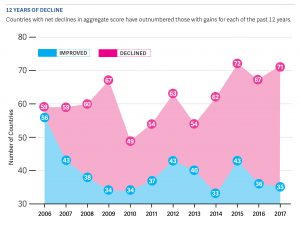

Figure 1: Freedom in the world 2018; Source: Freedomhouse

I wish it were so, but data from Freedomhouse show that liberal democracy has been in decline around the world for the last 13 years, and there is no reason to believe that illiberal and autocratic regimes will support changes to the global governance system that empowers pro-democratic constituencies at home.

Which brings us back to China’s treatment of the Uyghurs. What the ambassadorial squabble shows is that we may be too late to reform the world to suit liberal democracies. The balance has shifted. While China has surpassed the US and the EU as the world’s largest economy, it is still less than half of the combined economy of the OECD countries, and not likely to change any time soon. That in turn means that, on the whole, the current global order of governance without a government will continue – dragging along its legitimacy problems, since liberal democracies, who see the problems as bugs rather than a feature of the system, will not have the power to reform the world to their liking. Consequently, we are likely headed towards a mid to long term status quo in the global order where countries retreat in their respective blocks (EU, NAFTA, ASEAN, Eurasian Economic Union) protecting their internal constitutional settlements.

Figure 2: Global status by population; Source: Freedomhouse

Figure 3: 12 years of decline; Source: Freedomhouse

It will be different from the post Second World War balance of powers world between two powerful blocks, since the powerful actors will still have substantial interconnectedness, mostly in free trade, finance, migration and tackling human made climate change. There will be much greater openness between nations than there ever has been in human history, but it will not be on liberal democratic terms. There is also the possibility of greater regionalisation of political and economic life. Sadly, Fukuyama’s prediction of a future world order populated with liberal democracies will not come to pass, for while there might not be a great ideological struggle of what is the best political/economic order for humanity (the way that it dominated the Cold War era), there will be a struggle in liberal democracies of what is the best political/constitutional order for us as a people, as a country or a region.