This post is the English translation of a Welsh-medium article by Dr. Carys Jennings written for a special edition of the Primary First journal, edited by the Open University’s Early Childhood team ( Journal – NAPE )

One of the three questions that parents often ask during a meeting with their child’s teacher is, does he listen? Does he have friends? And the favourite – is he happy at school?

Happiness at school is important for parents, teachers and pupils because it can contribute to fostering a positive learning environment, which can also possibly help improve academic performance and the individual’s personal growth (Musgrave, 2017). I know from my own experience as a class teacher and researcher, that when pupils feel happy they are more motivated, they are better engaged and are ready to participate in activities and lessons, leading to better learning outcomes.

For parents, a happy school experience supports their child’s emotional well-being and helps them develop confidence. And when the pupils are happy, teachers can benefit from a comfortable classroom climate which often leads to better behaviour, easier relationships and effective teaching. Usually children spend a significant period of their lives at school therefore understanding what influences their happiness is a matter that should be considered seriously (Jennings, 2025). Overall, happiness promotes a sense of belonging and encourages enjoyment of learning.

What? Child wellbeing in the context of education in Wales

There has never been a time in Wales when such priority was given to the importance of children’s well-being and to children’s voices, significantly within the context of education. This can be seen clearly in the latest education reform documentation Curriculum for Wales (CfW) (2022), which has been implemented as a rolling programme across Welsh schools since 2022. Although the health and well-being of children has been the foundation of the Welsh education system for several decades, there is little research that shows that the system includes and responds to considerations related to children’s emotions by including their voices as influential factors.

Well-being or happiness?

Musgrave (2017) and Layard (2018) argue that investing in the well-being of young children is a valuable investment for the individual and for society, emphasizing that all adults share the responsibility of supporting the health and well-being of our youngest citizens. They also note that, like happiness, the concept of well-being is challenging to define and explain (Musgrave, 2017). With so many different definitions of well-being, there is a danger that its importance will be underestimated due to the lack of consensus on its meaning (Sharman, 2019; Manning-Morton, 2014). However, Sharman (2019) claims that, although an accurate or precise definition is difficult, there is broad agreement within research literature that well-being, in essence, includes positive emotions such as happiness and joy, which help to overcome negative feelings such as depression and sadness.

Ensuring children’s wellbeing has always, and continues to be, a shared responsibility between professionals (including teachers) and parents. Some methods of measuring well-being, such as testing specific growth and developmental stages from birth and tracking progress in areas such as response, hearing and weight, have continued over time (Bedford et al., 2013). However, recently there has been an increasing focus on children’s emotional well-being, both in the media and within domestic policies in Wales.

This change has been driven by reports such as The World Happiness Report (2025), The Good Childhood Report (2024) and Welsh Government research, ‘Well-being Wales, 2022: The well-being of children and young people’ which highlights the importance of children’s well-being and happiness. The Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act (2015) outlines recommendations for the well-being of communities, and the document Our Nation’s Mission (2017) acts as a foundation for current educational reforms to ensure the well-being of children within the curriculum. In CfWs documents (2022), Health and Wellbeing is recognized as a key area of learning and experience, reflecting how well-being is now central to children’s education in Wales.

Why happiness as a research focus?

The reasons for focusing on children’s happiness rather than their well-being stemmed from the belief that happiness is a key part of a wider general well-being. It was one of the themes that constantly resurfaced within my practices as a teacher and researcher. The well-being and voice of the child are core considerations when developing pedagogies as a teacher, to ensure effective and appropriate provision. Happiness is a central and essential aspect of a child’s emotional state, and when it is nurtured within the educational space, positive outcomes are more likely to occur. By prioritising happiness, we lay the foundation for emotional well-being, which in turn can lead to better learning, stronger relationships, and a more positive school environment.

Researchers in the field of Psychology and Sociology state that happiness is a subject of worldwide importance (Seligman, 2000; Haan, 2002). Happiness is considered an integral part of an individual’s well-being and which contributes significantly to the quality of life (Layard, 2020). Layard adds that the attention given to happiness in the media has doubled since 2010, and incidents involving mental health have increased over five times more frequently (Layard, 2020). This is also seen within published research with only small numbers existing in 2000 to around two thousand per year within educational, economic and psychological texts in 2020 (Seligman, 2011) but they rarely include the voices of young children. This leads us to the conclusion that happiness is a developing field, and could be considered a culture in itself.

Where? The importance of the learning enviroment

Any discussion about a child’s happiness will eventually turn to the world the child lives in; and any solution to education must address the adults who create the conditions in which learning takes place (Harrison and Hutton, 2013). It is widely believed that focusing on children’s happiness at school is essential because it plays a core role in their overall well-being and development, but it is often overlooked in favour of wider wellbeing, academic performance or a means of controlling behaviour.

Happiness in the school environment can significantly improve a child’s emotional and psychological growth, fostering resilience, creativity and the desire to learn. As someone who is very interested in this aspect, I believe that when children feel truly happy and supported at school, they are more likely to thrive socially, emotionally and academically. This is not only important for the children themselves, but also for parents and teachers, who benefit from seeing the children develop a positive relationship with the school. When a child’s happiness is prioritised, it lays the foundation for a lifelong appreciation of learning, as well as a healthier, more balanced approach to education. It is therefore believed that by highlighting the emotional side of education, we can create a more holistic, compassionate environment that supports the well-being of all.

How: The investigation

A qualitative study was carried out as part of my Educational Doctorate to investigate the influences on the happiness of young children at school, and to find out if this information, when shared with the children’s teachers, could further improve their understanding of their pupils and be a factor that contributes to the children’s emotional well-being. The participating sample was drawn from across three counties in Wales and from different schools in terms of size, language and geography. Although a small sample of nine children and six teachers were included within the data, the results were sufficient to demonstrate themes and relevance to classes across Wales (Bassey, 1981).

The procedure below was followed in terms of getting to know the participants and collecting the data with a second visit to ensure a correct analysis of what was collected in order to present it correctly.

Visit1- With teachers, explain the purpose of the research

Visit 2- speak with the children and gather the various data

Visit 3- share feedback from visit 2 and collect initial data from the teachers (current practice)

Visit 4- re-visit with the teachers to see if their practice had changed

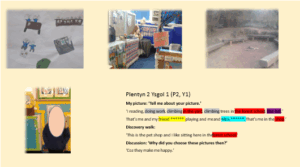

Braun and Clarke’s (2022) thematic analysis method was the vehicle for identifying themes within the data and the children’s responses were shared by collating works (below) that brought together their drawings, paintings, transcripts of the conversations and photographs of what made them happy at school.

The decisions made by the researcher about how the research is handled include accountability and taking responsibility for those decisions (Clark, 2017), this was in line with my personal values of securing children’s voices as a necessary source within research that relates to their worlds.

Conclusions were drawn and implications were discussed to further support educators as they plan provisions and to inform legislative makers of the power to listen to children’s voices for their happiness.

So: The findings

In conversation with the young participants it became clear that they understood the concept of happiness and they were able to explain their experience of it. They offered examples of their happiness when at school. One expressed that happiness was…’when playing in the outside area with friends’ and another felt happy when…’received a golden ticket from Miss’.

Schools have now established various ways of checking children’s feelings at the start of the day or a learning session by recording in various ways on a chart or digital app. This investigation was different as it’s purpose was to find out what in schoolenvironments influenced the children’s happiness. This offered new insight to the teachers in terms of their planning and provisions and enabled them to enrich what was offered.

The children’s conversations showed that there were positive influences on their emotions while at school and this brought them enjoyment. Among these influences were, indoor and outdoor spaces, activities in and beyond the classroom, people, and opportunities to choose which activity to do for themselves. This was one of the unexpected findings, namely that they not only they express a preference for doing certain things with their peers or teachers, but the fact that they also enjoy doing an activity independently. This was evident from all of the participants regardless of their age. There are implications here for educators to consider offering opportunities for children to engage independently as well as being involved in pair, group or whole class activity.

As for the teachers, their inclusion within the investigation offered them space and time to think about their practices, and to evaluate and refine their current pedagogies. By participating and discussing the data capture methods new ways of identifying the children’s preferences, understanding and experiences of their happiness at school were introduced and opportunities for incorporating these within their normal routines became evident. Their participation was also to secure opportunities for young children to maintain their participatory rights as Welsh citizens via multi-modal communication methods. Following the investigation, the teachers recognized that this process helped them to foster a deeper understanding of their pupils’ emotional intelligence, laying the foundation for more meaningful and inclusive interaction in the classroom.

Investigating children’s happiness at school through multi-methods, such as combining, interviews, paintings, photographs and participatory activities, allows a more nuanced understanding of their emotions and experiences. By embracing multiple perspectives, educators and researchers can create more responsive strategies that truly address the factors that shape children’s happiness and well-being in schools and offer a broader and richer way of understanding and knowing the individual. This could also inform policy makers of the importance of ensuring consistent and suitable ways for children to be able to voice their opinions and experiences and for us as educators to be able to respond confidently to parents… this is what makes them happy at school.