Mrs Eleonora Teszenyi, Lecturer in Early Childhood

I joined The Open University in September 2019 and previously taught on both undergraduate and postgraduate degrees including the Masters programme in Early Years. Before entering Higher Education, I had worked in the early years sector for 19 years as an early years practitioner, early years teacher, Local Authority advisor and children centre teacher in one of the most disadvantaged areas of Leicestershire. Although working in Higher Education, I have remained close to practice: I am still involved with supporting early years practitioners, and my PhD study focuses on early childhood pedagogy and practice.

Thanks Eleonora. Can you tell us….

The last book you read: I always have at least two books on my bedside cabinet (often more), one of which is fiction. A novel I long to read to switch my brain off at the end of the day. But I must admit, at the write-up stage in my PhD, this feels rather like a luxury so often I pour over research books in preparation for the following day’s writing. Before you condemn me to be rather ‘sad’, let me confess to reading an easy-going novel during my summer leave. Nothing high-brow or particularly sophisticated (without wanting to offend the author), just ‘nice’. It was by Delia Owens and the title is ‘Where the Crawdads Sing’ and offered a bit of escapism.

Your ideal holiday destination: I would very much like to hike on the Inca Trail in Peru, starting from Chillca, up to the lost city of Machu Picchu. I am fascinated by ancient civilisations, although I cannot claim to know too much about them. It is more like an enthusiastic interest of a novice. Once I am in that part of the world, I’d like to travel around in South-America.

What you do in your spare time: Anything that is outdoors. Our family holidays are always about adventure and I love it all: sea kayaking, canoeing on white water, hiking, rock climbing, caving or skiing, they are all fun. I must admit, I am not too keen on biking, particularly not mountain biking. I also love pottering in the garden, growing our food on our allotment, cooking it all in a cauldron on open fire… you get the picture. Wind in my hair, sun on my face, soaked by rain… I don’t mind but love the snow the most!

Dr Joanne Josephidou, Lecturer in Early Childhood

I joined the Open University in September 2019 but before this, I was a primary school teacher for many years before entering Higher Education, as a teaching fellow, in 2009. I taught on Initial Teacher Education programmes at the University of Cumbria before joining the Early Childhood Studies team at Canterbury Christ Church in September 2014. I have taught on a variety of modules and have a particular interest in supporting students to develop early research skills. My PhD focused on appropriate pedagogies with young children and how practitioner gender may impact on these. Currently, I am working collaboratively on a piece of research which focuses on babies’ and toddlers’ opportunities to engage with the outdoor environment and nature.

Thanks Jo. Now tell us…

The last book you read: I discovered Helen Dunmore recently and read lots of her books over the summer; I have really enjoyed them all.

Your ideal holiday destination: France or France or France – I just love it!

What you do in your spare time: I love spending time with my family; I have three sons who make me laugh, wind me up and help me to see the world in a different way.

Dr Lucy Rodriguez-Leon

I joined the Early Childhood Team in 2019 and I work on module E109, Exploring perspectives on young children’s lives and learning. As a former OU student at both undergraduate and postgraduate level, I feel particularly connected to The Open University. Before teaching in Higher Education, I worked at a state-maintained nursery school for 16 years. I still miss working with children, so I really enjoy hearing about our students’ experiences in their early childhood settings.

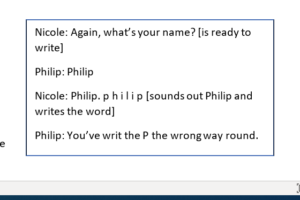

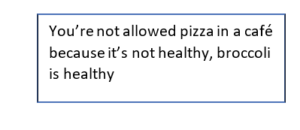

My PhD focused on early childhood literacies; more specifically, the research explored young children’s everyday encounters with written and multimodal texts, and how their experiences shape their understandings of themselves as readers and writers. I’m a member of the UK Literacy Association and co-convener of the Early Years Special Interest Group, where we advocate for broad and balanced approaches to early literacy education. I am currently co-writing an online course on promoting reading for pleasure in the primary and EY classroom, which will be freely available on Open Learn in the Autumn.

What do you like to do in your time off?

One of my favourite places to visit is Northumberland, where I like to walk in the Cheviot hills and explore the ruins of Roman forts. It can be a bit wet and windy at times, but the wilderness and spectacular views are simply stunning.

What’s the last book you read?

I’m currently reading ‘How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America’ by Clint Smith. It’s a hard hitting read, telling of the author’s experiences as he travels to plantations, memorials, cemeteries, museums and prisons connected with slavery in the USA.

What do you do in your spare time?

During lockdown, I discovered a love of gardening and now appreciate the phrase, ‘enjoying the garden’! However, I am a complete novice and have a lot to learn. I also enjoy cooking and dining out!