Sarah Middle is a PhD student in the Department of Classical Studies. She tweets at @digitalshrew

—-

During the first two weeks of September I took part in the Institute in Ancient Itineraries, an international collaborative research project funded by the Getty Foundation and led by King’s College London. The main aim of the project is to develop a digital proof of concept to facilitate the study of Art History in general, and the art of the Ancient Mediterranean in particular. This prototype will draw strongly on the concept of object itineraries, the journeys that objects take through space and time, including their interactions with people and organisations.

Project participants came from all over the world and had a wide range of academic backgrounds, specialising in areas such as Art History, Archaeology, and Computer Science. Everyone had some Digital Humanities experience, which included spatial analysis, data modelling and 3D visualisation. At the start of the two weeks, we divided ourselves into three groups – Geographies, Provenance and Visualisation – based on our previous skills and experiences. However, these terms turned out to be more problematic than anticipated, with considerable overlap between the three groups.

Welcome #AncientItineraries members! pic.twitter.com/yKypWkS8dR

— Stuart Dunn (@StuartEDunn) September 3, 2018

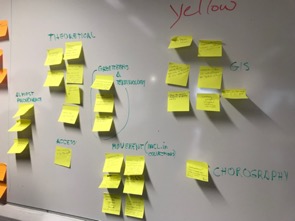

I was part of the Geographies group with four other participants. We fairly quickly renamed our group to Space, as we felt that this term encompassed more than the notion of Geographies. Spaces we discussed included those in the physical world, imaginary spaces, museum/gallery spaces, and the spaces depicted in artworks, as well as the conceptual space of intellectual networks. We then discussed ways of bringing these spaces together digitally to provide an effective representation of the ‘itinerary’ of an art object.

Many of our discussions centred on the idea that there is a huge amount of Ancient Art related data online already, which is held by different institutions and represented using different standards and formats. What we hoped to do was to develop a specification for how this data could be connected, along with documentation about how it could be used, written clearly enough as to be understandable by people with varying levels of technical experience. We felt that finding a way to bring existing material together might be more sustainable in the long-term than building something completely new.

The Provenance group created a mock-up image of an online resource to find provenance details of art objects (incorporating information about related people, places, dates and materials), and had thought about renaming their group to Context. The Visualisation group had discussed different methods and meanings of representation, including appealing to senses other than sight; as such, they considered renaming their group to Representation. All three groups, therefore, realised early on the limits of the terms that defined them, and sought to develop ideas relating to a much broader context. Additionally, all groups discussed the idea of how best to digitally represent uncertainty about any of the information associated with an object and the reasons why particular interpretations have been suggested.

The question of uncertainty keeps cropping up at #ancientitineraries. We really need a #digitalhumanities group / conference / workshop on getting us all talking the same way about uncertainty / creating an ontology of the unknown.

— Ryan Horne (@RyanMHorne) September 4, 2018

Realizing a basic truth that studying/ appreciating/researching art of any period is a *spatial process* in myriad different ways #AncientItineraries

— Stuart Dunn (@StuartEDunn) September 7, 2018

Our group discussions were informed by excursions to the Soane Museum, Leighton House and the British Museum. During the second week, we formed four new groups, which each selected three well-documented items from these collections and discussed the information that is known about them, as well as how this information should be represented. My group decided to base our choices on the theme of whether the object had been taken from the place where it was created – our three objects incorporated:

- An object that remains in situ (for this we visited the London Amphitheatre)

- An object that has been taken from its place of creation (Ephesian Artemis at the Soane Museum)

- An object that has been taken and then returned (Leighton’s painting of Clytie)

In addition to each object’s relationship with the place where it is currently situated, we also discussed the places and people depicted, the objects’ itineraries through space and time, and the people involved.

As well as discussions among ourselves, over the course of the two weeks we heard talks from staff at King’s Digital Lab, the National Galleries in London and Washington, and the Institute of Classical Studies. These introduced us to existing projects in a similar subject area and issues they had faced, which often related to technology and sustainability, as well as access, usability, and the representation of complex ideas within the restrictions imposed by metadata and cataloguing systems.

.@nottinauta demonstrates Recogito https://t.co/MfwyPnBgDh #ancientitineraries @Pelagiosproject pic.twitter.com/iGKYQSJt3U

— Sarah Middle (@digitalshrew) September 4, 2018

We ended the two weeks with the seed of an idea to bring together the findings from all three groups, which will possibly take the form of an interactive online publication. This will be developed further at the next Institute in April 2019 to produce a specification for our proof of concept, to be built by King’s Digital Lab. In the meantime, we are in the process of producing a set of white papers that outline the issues identified by each of the Geographies/Space, Provenance/Context and Visualisation/Representation groups.

As well as having this incredible opportunity to take part in an international research project, I came away from the first Institute having made new friends, and with new ideas about how to approach my PhD topic. I would like to thank King’s College London and the Getty Foundation for their support and funding and am looking forward to seeing what the next Institute brings.

By Sarah Middle