Marilyn Booth completed her MA in Classical Studies with the OU in September 2018. Her dissertation focused on the sensory experience of everyday Romans in the home, working environment and public spaces. Her interest continues and this report enabled her to consider likely sensory experiences of one such relatively undervalued public space, the Circus Maximus.

I visited the Circus Maximus in late May 2019, two days after the opening of a new virtual/augmented reality exhibition (The Circo Maximo experience) in the site’s archaeological area. While much of the site remains unexcavated and open to the public as a free space, I had been aware that I could visit the archaeological area, which has largely been excavated and revealed in the last fifteen years (Buonfigio, 2015). As Figure 1 below shows, there are 8 information points dotted around the site at which visitors direct their headsets in order to initiate a dedicated virtual reality presentation of the site.

Some 40 minutes’ worth of such information is provided, centred around 8 broad themes:

- The Valley and the origins of the Circus

- The Circus from Julius Caesar to Trajan

- The Circus in the Imperial Age

- The Cavea

- The Arch of Titus

- The Shops of the Circus (tabernae)

- The Circus in the medieval age and in modern times

- “A day at the Circus”

There is also an opportunity to experience a panoramic viewpoint from the top of the medieval Torre della Moletta. As such, the overall experience provides a relatively comprehensive introduction to the life of the Circus for visitors, giving a real sense of the site’s evolution over time, as well as providing a useful introduction to the role of religion and the site’s potential significance in archaic Rome. It also provides a unique sensory experience in its own right, adding new elements to any potential sensory analysis of the site.

Experiencing the space

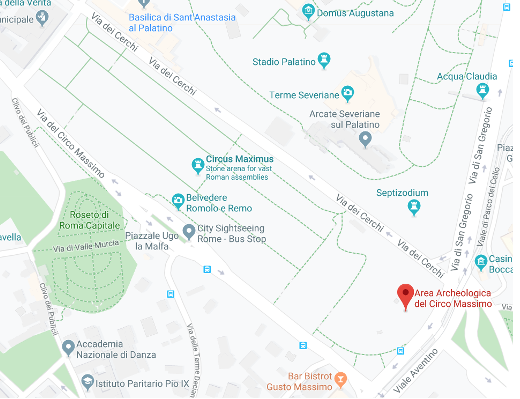

The area covered by the visit represents a relatively small portion of the south eastern (Porta Capena) end of the Circus site, as shown in Figure 2, with sections of the cavea and tabernae open to view. The area corresponds to the curved end of the stadium, which also housed a triumphal arch dedicated to the Emperor Titus.

The visit took place between 10 and 11.30 am on an unseasonably cool May morning. Temperatures were in the early 20 degrees Celsius, with both sunny and overcast skies witnessed during that time period. The sun was almost directly overhead for much of the visit duration and would remain so for the majority of the day. In the site’s early iterations, there would have been no respite from the elements. While the current site contains none of the shelter that would have been available to users in later iterations, it was obvious that there was little respite from the overhead sun at many points in the day for both spectators and those involved directly in the action in the middle of the Circus space. While on an obviously much smaller scale, a recent visit to Shakespeare’s Globe for a summer afternoon performance showed that even roofed enclosures do not provide complete shelter from the midday sun.

The reconstructed course

The virtual reality presentation certainly brought the site to life, and from a sensory perspective bring both the colour and size, as well as the spectacularly opulent nature of the site into sharp focus. Visually, this is a stunning and evocative realization of the site. Aurally, sounds including the roar of the excited crowds, the galloping horses and grinding machinery are also evoked. Less easy to replicate are potential smells, and taste elements, although forcing the viewer to sit down while a virtual race occurs (presumably to avoid complete disorientation and dizziness) was a useful device. Equally, the ability to touch the various extant construction materials, and interact with surfaces including elements of the cavea and tabernae, enriched the experience. Those surfaces ranged from the rough brickwork of the tabernae, to original roadways and passages, to the smooth and cool marble remains of the Arch of Titus which were scattered across the site.

Once “inside” the virtual reconstruction, rich golds and reds marked the starting gates, and the viewer is even given a viewpoint from the spectacularly lavish emperor’s box at one point. Unsurprisingly, the view from both here and the judges’ box / Temple of Sol opposite were clearer and less constricted than many people within the stands would have experienced.

Figure 3: Reconstruction of the Carceres or starting gates at the straight end of the course (Virtual views taken from Circo Maximo’s Instagram account and website)

The demonstration effectively showed how the course evolved from an ad hoc space used in the archaic period, with elements such as the early shrine to Consus eventually being incorporated into the splendidly opulent Euripus or spina in the middle of the racetrack area. While citizens would undoubtedly have been exposed to grandeur at other iconic sites, including forums and temples, clearly there would have been a sharp and highly visual contrast with the lack of splendour in the majority of non-elite homes: the insulae buildings dotted across the city. However, as the presentation tracked the development of the course over time, it became clear that questions could be asked about just how clear views were for spectators, with the amount of material housed on the Euripus increasing over time, creating a crowded and distracted space that could only have obstructed the view for many audience members. The obelisk visible in the virtual image in Figure 4 below is now located in a square beside the Lateran Palace, and personal photographs show that it does, in fact, split the view of the site for the viewer.

Words associated with “dust” are quite common in ancient descriptions of the site, and that dusty element was recreated as racing quadrigae thundered past, conjuring up clouds of dust. The virtual element also vividly brought home the Circus’ key role in iconic historical events, including its position as the starting point for the fire of AD 64.

Tabernae

The tabernae, such as that depicted in Figure 7, evoked the type of construction used in the Markets of Trajan, perhaps not unexpected given Trajan may have been the last emperor to develop the site. As such, his architects and building teams may have used similar techniques and materials, albeit on a different scale. While there are relatively limited tabernae remains at the Circus, they were surprisingly complete in some instances. I was able to physically stand up upright in one of the “shops” and stretch my hands out without reaching either side wall, a contrast to the experience of a researcher who had previously told me that they were unable to stand fully upright in one of the shops above the insula dell’ara coeli. At 1.55m tall, I am relatively short by both modern and Roman standards, so this may or may not have much significance. However, it showed that some people at least would have had a relatively comfortable experience while in the work or leisure environment that these small shops represent. However, it is also clear that that comfort would have been somewhat compromised at various intervals during a day’s activity at the Circus: during particularly crowded moments, for example during arrival to or departure from the site, these would still have been constrictive spaces for people working within them as crowds congregated in the relatively narrow corridors and streets around the outside of the building, cutting off light and space in which to move.

During races, workers and customers would likely have heard what was going on in/at the racetrack and performance space behind the back wall of the relevant taberna, but been relatively isolated from the action, only looking out at a windowless corridor (Figure 8) or road around the circus which would likely have been packed with people. As can be seen from Figure 8 below, even the relative height of the vaulted ceiling of the walkway would have provided little respite from an otherwise restrictive space. Evidence apparently suggested that shops, cafes (Figure 6), fullonicae and even latrines were dotted around the perimeter of the site in these purpose built spaces, resulting in a richly layered smellscape (Forichon, 2019) experienced by the workforce, and by spectators as they entered and left the perimeter of the site.

Latrines

I did not see the latrines which co-existed with the shops of the tabernae area, although their presence would surely have been felt by visitors in such a confined space. I was struck by their likely co-existence with the shops, and reminded of visits to concerts in purpose built modern stadia and concert venues (London’s Wembley Arena, Belfast’s King’s Hall and Dublin’s Point Depot) where, by the end of the night on any given event, toilets became blocked, slippery, smelly and generally unsavoury spaces. Assuming each of the Circus’s 150-250,000 visitors made at least one latrine trip on a day’s visit to the site, the chances are that these latrines must have also become blocked and equally pungent relatively quickly. Associated smells may have been limited by the proximity of purpose-built fullonicae, which could have disposed of liquid urine quite quickly and effectively. Equally, though this type of facility would have created their own distinctive sensory environments for both workers and onlookers.

The Arch of Titus

The Arch is a key feature of one of the InfoPoint stops, and is reconstructed in much detail, suggesting that it was at least as impressive as its namesake in the Roman Forum. However, that reconstruction has been decidedly whitewashed, as shown in Figure 9 above. While still impressive, it remains difficult to assess whether the arch had a similar colour scheme to other monuments in the imperial era. Surprisingly, much purported original material was available to view in a relatively compromised external position, as shown in Figure 10 below. The material on view undoubtedly attests to both the size and quality of the structure. This material was somewhat weathered, but still impressive – it struck me as I was walking around modern Rome that perhaps its closest modern equivalent in terms of visual impact is the Vittoriano which is often dazzling to the eye when struck directly by sunlight. I have since seen almost new Carrara marble in London’s Spencer House visitor attraction and it quite literally gleams even in small quantities, again suggesting that the arch could have had a noticeable visual impact.

Conclusion

Visiting the archaeological site certainly brought the detail in 21st Century excavation reports to life. Those reports actually seem to have downplayed the scale of the extant evidence. While a comparatively small area of the site has certainly been uncovered, it is nevertheless quite an extensive space. Interacting with the remains, both real and virtual, enabled a number of conclusions on the site’s likely sensory environment. The virtual/augmented reality elements of the new visitor experience added a further sensory experience which could itself be productively explored in future research. Many questions certainly remain on the site and its usage, but this visit represented a useful first step in assessing how the sensory experiences within the Circus Maximus could be productively explored in a sustained research project.