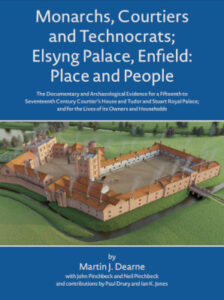

Dr Martin Dearne has been an Associate Lecturer with The Open University for twenty years, and has taught on many of our Classical Studies modules (AA309, A209, A251, A330, A219, A229, A105, A151, A112). He is the author of six books, the most recent of which is an archaeological study of Elsyng Palace in the London Borough of Enfield. In this blog post, Martin tells us more about Monarchs, Courtiers and Technocrats; Elsyng Palace, Enfield: Place and People: The Documentary and Archaeological Evidence for a Fifteenth to Seventeenth Century Courtier’s House and Tudor and Stuart Royal Palace; and for the Lives of its Owners and House

Dr Martin Dearne has been an Associate Lecturer with The Open University for twenty years, and has taught on many of our Classical Studies modules (AA309, A209, A251, A330, A219, A229, A105, A151, A112). He is the author of six books, the most recent of which is an archaeological study of Elsyng Palace in the London Borough of Enfield. In this blog post, Martin tells us more about Monarchs, Courtiers and Technocrats; Elsyng Palace, Enfield: Place and People: The Documentary and Archaeological Evidence for a Fifteenth to Seventeenth Century Courtier’s House and Tudor and Stuart Royal Palace; and for the Lives of its Owners and House

Hello Martin, and congratulations on your new book! Please could you start by introducing our readers to Enfield and its history?

Hello Martin, and congratulations on your new book! Please could you start by introducing our readers to Enfield and its history?

Enfield today is a London borough – at the top centre of Greater London just south of the M25 – made up of two or three distinct Medieval villages in the Lea Valley that expanded into towns and eventually got swallowed up in the urban sprawl of the capital. Enfield itself was the most northerly of them, from the Norman conquest on quite a small market town in what was then rural Middlesex, but dominated by the nearby royal hunting forest of Enfield Chase. It still has a market square opposite where a manor house used to stand, but as the town grew in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries it became best known for the industries that grew up east of the original town along the River Lea (the largest tributary of the River Thames) such as that making Lee-Enfield rifles.

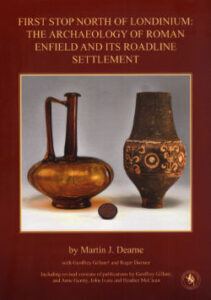

Your first book on Enfield (First Stop North of Londinium: The Archaeology of Roman Enfield and its Roadline Settlement) dealt with the ancient history of the town. How did you come to write that book? And what did you discover about Enfield’s Roman past?

I was born in the borough and the first archaeological dig I ever went on was with the local archaeological society on a Roman site here. After many years at Sheffield University when I moved back to Enfield I got involved in that society which was active at the time in excavating a Roman settlement that lay on Ermine Street – the main Roman road north out of Londinium which ran ultimately to York and beyond – but a little at a time in people’s back gardens. Nobody had tried to take all these little pieces of a jigsaw and put them together and the book grew out of the process of doing that. The result was a picture of the first roadside settlement along the road once you left Roman London, a settlement that combined farming with providing for travellers, probably had a mansio (official ‘hotel’) and lay in a wider landscape that may have included a tannery site and a large estate farm.

This new book moves the story forward by looking at a later period of Enfield’s history, and at a particular site – the royal palace of Elsyng. How did you come to that topic?

Yes, that’s right. While I was working on the first book I was asked to direct new excavations on the site of this Tudor and Stuart palace. Some very impressive remains of it had been excavated in the 1960s, but nothing had been done on the site for about 40 years and, as it is a Scheduled Ancient Monument, English Heritage required a professional archaeologist to lead the local team who wanted to uncover more of it. And that fairly rapidly became an annual excavation taking in student training, community open days and even a TV documentary. But, as the team (which includes two other current or former OU Associate Lecturers) uncovered more and more of the palace, it became more and more important to publish what we had found and link it to the people who had once lived here. Surprisingly royal palaces like this are in fact a very under explored part of the national story and Elsyng was also the most important element in putting Enfield on the map over about 300 years. So once I finished the book on Roman Enfield I decided that I would try and research its history as well as publish the archaeological work I had led.

Can you introduce us to some of the historical figures you study in the book? Maybe you can tell us which figure interested you the most?

I could tell you about a variety of people who I look at, from an Earl of Worcester in the Wars of the Roses who was called ‘the Butcher of England’ to Elizabeth I who lived at Elsyng at times when she was a girl. But one I got particularly interested in was John Carleton. Before it was a royal palace, Elsyng was held by Sir Thomas Lovell – one of the technocrats who ran early Tudor government. He was very rich, had vast estates all over the country, many governmental positions and was constantly being visited here by Henry VII and VIII. But it was Carleton, his own ‘Receiver General’, who ran Lovell’s private affairs and then organised his lavish funeral when he died in 1524 and had to disentangle his complex financial affairs as his executor. And it is through Carleton’s accounts books with their detailed pay records and tradesmen’s bills that we get an insight into how Elsyng functioned as a ‘courtier’s palace’ with a staff of about a hundred. He is the sort of figure who stands just outside the spotlight of history, but without whom those in the spotlight couldn’t have functioned.

How did you go about researching the book? Was it archival research, archaeological fieldwork, or both?

The site of the furnace of the boiling house at Elsyng. Whole sides of meat were boiled in a large vat set over the furnace.

It was very much both. I reassessed the 1960s excavations and synthesised the 16 years of those I had up to that point directed myself, which in some ways was the easy part. The more difficult was writing the history of the site and the people who lived there because it meant getting into late Medieval and early Modern studies which I didn’t have a background in. Fortunately I had colleagues from the excavations, one of whom took on photographing hundreds of documents in the National Archives and elsewhere and another of whom taught himself to read and transcribe them – because often they were written in things like Tudor secretary hand which at first glance is as hard to read to the uninitiated as cursive Latin. Even then though it meant trawling through and cross referencing vast numbers of printed ‘calendars’ (summary publications) of documents. In fact it is only the fact that so many of these can now be read on line that made this side of the research possible.

Did you find many links between the Roman and later periods of Enfield’s history?

To borrow a phrase, it’s about location, location, location. The Roman settlement in Enfield was here because it was a convenient distance out from Roman London for travellers to break a journey. In the same way the palace was near enough Medieval and Tudor London to easily reach it, but far enough away to escape its plague outbreaks and develop a prestigious house in a large estate. Then where exactly the palace was sited was in part determined by the survival of Ermine Street; in the 1430s, when it was first built, Roman roads like Ermine Street were still the backbone of the road network in Britain.

Which is your own favourite historical spot in the town of Enfield – and why?

Well, it would have to be the site of Elsyng palace, but one specific spot on the site. At that point you can see over 1,600 years of Enfield history in one go. Look in one direction and there is a modern road that follows the line of Ermine Street to an eighteenth century bridge over a brook that stands where a Roman bridge or ford once did. Turn round and across the modern park it edges you can still trace the approach road to the palace that ran off of it. And turn half way back and look uphill and there stands the early seventeenth century Forty Hall, the country home of a Lord Mayor of London (the excavations I have directed around and inside which look dangerously like turning into another publication !)

Thank you Martin, and congratulations again on this new book!

Monarchs, Courtiers and Technocrats is available to buy via the website of Enfield Archaeological Society: https://www.enfarchsoc.org/publications/