Walking ‘in the footsteps of’ a famous author has long been a favourite past-time – and not just one of mine. Since at least the 1790s, when writers began to describe their favourite walks, visitors have retraced them. Rousseau’s descriptions of his walks in his Rêveries on an island in the Lac de Bienne in Switzerland brought all sorts of visitors keen to mimic his state of mind; William Cowper’s walks around Olney, lovingly described in his poem The Task also prompted admirers to put on their boots and follow his path. But the late eighteenth century also saw the birth of the desire to follow in the footsteps of literary characters into a real landscape, as in the case of Loch Katrine or indeed Exmoor, that is, if you have read Lorna Doone (1869), and this is today’s adventure.

R.D. Blackmore’s novel used to be a set text in schools, was still a children’s classic in my day, and is periodically revived as costume-drama, but all the same these days ‘Lorna Doone’ country has faded in much the same fashion as the territory of The Lady of the Lake – the topic of my last post. In Lorna Doone, Blackmore drew upon a fund of local legend, anecdote, and historical titbit detailing the story of the seventeenth-century Doones, a clan of aristocrats who, outlawed and landless, took up residence in a remote Exmoor valley and terrorised and robbed the natives until they were eventually cleared out by government forces. Blackmore combined this material with the tradition of John Ridd, a giant among local men; the story of a local highwayman, Tom Faggus; and the tale of the Monmouth rebellion. He then brought the whole to life with striking descriptions of landscape, almost pre-Raphaelite in intensity.

There is still a Lorna Doone hotel in Porlock, the girl behind the bar, as I discovered upon asking, has very little idea of the reason behind its name. The gift-shops may sell ‘Lorna Doone’ biscuits, thimbles, and coasters, but there is hardly an edition of the book itself to be had. It seems the very strategy that enabled Lorna Doone to be imported into the landscape and detached from the author has been the text’s undoing, as it has decayed back into history in popular memory. The captions in the Exmoor Visitor Centre manage to unravel the magic mixture of fiction and past that so entranced the Victorians: providing information on the tradition of the Doones, they offer a health and safety notice designed to police the unwary literary tourist: ‘FACT: Did you know that Lorna Doone is a fictional character?’ Spoilsports.

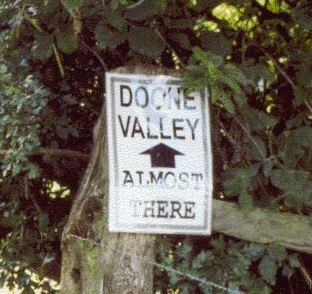

Yet I must admit the charm of visiting Doone country is in many ways enhanced by this spectacular forgetting of the book. Nowadays there is remarkably little competition to take the classic literary walk, following in the footsteps of the young John Ridd up Badgworthy Water, past the stone monument to Blackmore, and up the ‘water-slide’ into the Doone Valley. Imagination is needed to squint past the realities of the farm campsite, it is true, but once past it, if you can’t imagine the figure of John Ridd, you may just be able to catch a sight of Edwardian riding-habits trailing from small shaggy ponies up the bracken-fringed path ahead. Thirteen-year-old John Ridd’s first-person account of his excursion up Badgworthy Water is the defining episode of Lorna Doone, the one that sticks in the imagination, and that has inspired tourists from the nineteenth-century onwards to retrace his footsteps:

I stood at the foot of a long pale slide of water, coming smoothly to me, without any break or hindrance, for a hundred yards or more, and fenced on either side with cliff, sheer, and straight, and shining. The water neither ran nor fell, nor leaped with any spouting, but made one even slope of it, as if it had been combed or planed, and looking like a plank of deal laid down a deep staircase.

As John’s account suggests, Lorna Doone represented Exmoor as a place of historical romance, and wildly picturesque landscape. Unfortunately, however, the Exmoor scenery, and in particular Badgworthy Water and the Doone Valley, were not (and are not) anything like as picturesque as Blackmore had made them out to be. In 1887 Baedeker’s Guide accordingly warned tourists that they were liable to disappointment when they identified the water-slide, so far short did it fall from the sort of expectations generated by the book. As I found out for myself, even in a wet summer the water-slide does not look anything formidable; Doone Valley itself looks like a fairly undesirable camp-site.

Despite Baedeker, Blackmore’s extraordinary writing of intensely observed detail, together with the inclusion of many actual mappable places, promoted an industry in identifying Blackmore’s locations, whether real, thinly fictionalised, or altogether and frustratingly fictional. The burial place of Lorna’s mother, for example, was for a while pointed out by the vicar of Watchet, and there was a spirited argument over the rival claims of Hoccombe and Lank Combe as the original for the Doone Valley, settled only by the intervention of the Ordnance Survey in 1968 and clinched by a plaque.

While it was perfectly possible to publish and sell maps, detailed descriptions of the Doone Valley walk, editions extensively illustrated with photographs of the localities, and full-length studies such as F. J. Snell’s The Blackmore Country (1906) which came complete with no fewer than fifty photographs, the core of the romance remained as nearly inaccessible as it is supposed to be in the fiction. The American traveller who wrote up his visit in 1893 for The Atlantic Monthly is forced as a result to pay tribute to ‘the might and majesty of genius:’

For, lovely as this enchanting valley is when seen in its length and breadth, it yet needed the power of a creative imagination to describe so vividly and circumstantially the scenes of a tale of 200 years ago.

What is not there – and after all, historical romance never has been there, even for the author – is in this account recuperated as just as important to the literary visitor as what is there. The power of fiction is actually confirmed by the tourist’s disappointment, which drives the reader back to memories of the text in preference to the real landscape. And, of course, to the really excellent cream tea down at the bottom of the walk, in Malmsmead. A real literary tourist experience all round.