Photograph by Peter Smith © Jane Austen’s House Museum.

I love going to Chawton. It’s deepest, most idyllic Hampshire, all red-brick cottages, slightly wonky tile roofs, and enormous swaying candled horse chestnuts. It’s everything that Jane Austen is supposed to be but wasn’t really. It’s worth remembering that Chawton Cottage was smack on a curve in the main road from Southampton to London, which is one reason why Austen’s brother bricked up two windows when he offered the estate cottage to Mrs Austen and her two daughters; it ensured privacy from travelling gawpers. It’s worth remembering, too, that for most of her life, Jane Austen was writing in and about wartime England. Still, I’m not immune to a country idyll, especially one that ends in the Cassandra’s Cup tea-room, where I fetch up along with a roomful of women bringing their mothers as I have done, to chat a little about Austen while drinking tea from proper bone china.

Like all the sites I’ve visited in the course of this blog, Chawton Cottage is an invention and a fantasy, with chips of the real buried at its heart to assure its imaginative power. The piece of writing by far the most important to the invention of Chawton Cottage as the centre-piece of ‘Austen-land’ was not by Austen but by a woman called Constance Hill, a book entitled Jane Austen, Her Homes and Her Friends (1902). Rivalling myself for the title of most dedicated literary stalker, Hill describes a tour taken in the company of her sister with the object of visiting all the locations they can find that are associated with Austen. In documenting this hunt, Hill’s book not only locates and records places associated with Austen; it also models a way of visiting and enjoying these locations for future tourists. This involves drawing together personal experiences of place by gathering up such descriptions as can be gleaned from Austen’s letters, biographical information, details from the novels themselves, and supplementing them with information poached from other literary contemporaries.

One typical chapter of the book opens with an account of Hill’s drive to Austen’s birthplace at Steventon. Enlivened with information about Austen’s parents’ move to the village, derived from the Memoir of Jane Austen (1869) written by the author’s cousin James Austen-Leigh, the chapter tells how Hill identified the site of the old parsonage through quizzing the locals, checked what the locals said against the testimony of Lord Brabourne’s edition of Austen’s Letters (1884), sketched the site, pictured the now vanished house with the help of ‘two old pencil views’, noticed the stumps of elms described in Austen’s letters, remembered the description of the shrubbery of Cleveland in Sense and Sensibility and wondered whether this was the original, and engaged in fanciful reanimation of ‘two girlish forms… Jane Austen and her sister Cassandra.’ The following chapter uses information about Mary Russell Mitford’s roughly contemporaneous life just down the road recollected in Our Village (1824), adds details drawn from Gilbert White’s diaries at neighbouring Selbourne, and quotes from Anna Lefroy’s manuscript memoir to give more substance to an account of Jane Austen’s daily life. To peep ‘in through the window of the parsonage’, Hill plunders both the description of Uppercross in Persuasion and Austen’s favourite poet William Cowper’s description of his room at Olney in the 1780s in his poem, The Task. On reaching Chawton Cottage, Hill engages in similar imaginings to reanimate it as Austen’s home despite its contemporary (and, as she sees it, unfortunate) function as a working-man’s club.

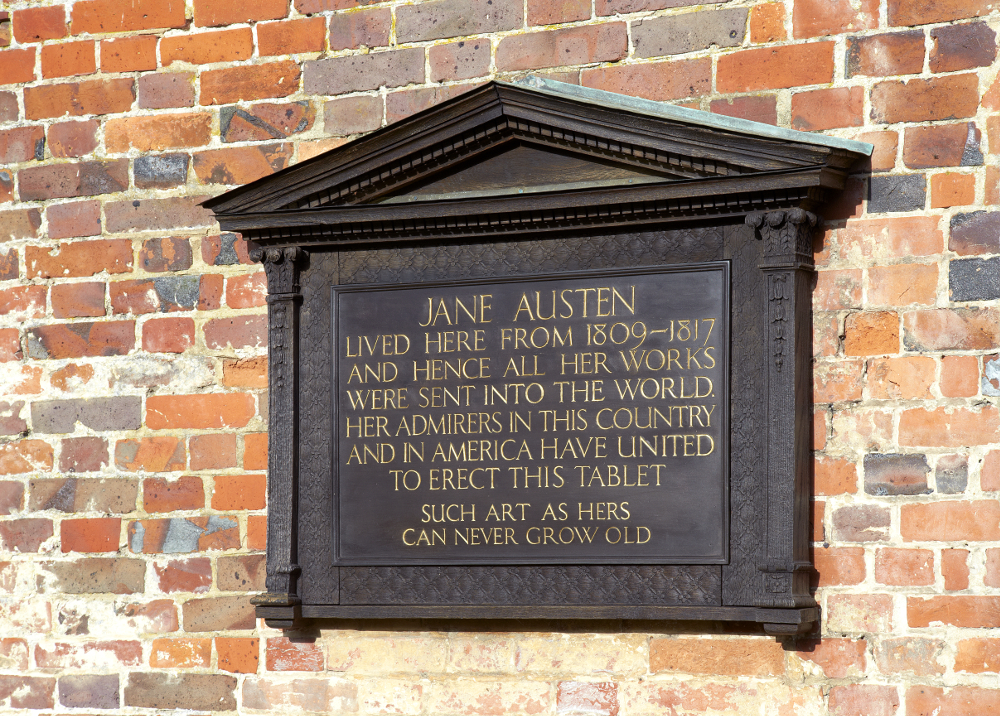

Hill’s efforts to imagine Chawton Cottage at the heart of what she called ‘Austen-land’ culminated in a campaign to place a commemorative marker on the building. In 1917, she and her sister were key players in the funding and design of a plaque on Chawton Cottage to mark the centenary of Austen’s death. The plaque, and the ceremony surrounding it, sealed Austen’s importance in guaranteeing the continuities of English life in the face of historical change. The speeches given at the unveiling ceremony present the cottage as a site of continuity, as a place of refuge and source of consolation in wartime, and as the classic literary ground of England. In the words of one speaker recorded in a scrapbook held in the Chawton archives:

It is perhaps a remarkable thing that, in these days of war, we can turn aside, even for a day, from the sterner demands of the moment to come together to pay this homage to the genius of Jane Austen, and may we not take from this thought a new hope of the civilisation that we are fighting together to save?

Turning aside from sterner demands, I take my mother’s arm, and we slip away into the tea-room to pay homage to genius.