Over the past couple of months I have taken you on numerous trips to writers’ houses scattered all over the place : we have trekked across the moors to the Brontës’ home in Haworth, admired the desk at Walter Scott’s house in Abbottsford, and felt dizzy and bewildered while touring Hans Christian Andersen’s home in Odense. Recently, I have extended my thoughts from writer’s home, to writer’s landscape. I have been considering what putting a writer at the centre of a landscape, rather than a house, does to the landscape for the reader. The effect, I feel, is particularly interesting when the writer in question is a woman, as it reveals so much about how a woman-writer might think about writing, and be thought as a writer, in relation to the domestic.

One might consider in this respect Marie Corelli’s garden-folly. This is set in the garden of the house she leased in 1899 and eventually bought, Mason Croft, in Stratford-upon-Avon. She renovated the eighteenth-century folly as her summer study. Lavishly ornamented with leaded glass in the windows, dark oak panelling and cabinet bookcases punctured with cut-outs of hearts, vine-covered and picturesque, the total effect is sweet, pretentious, aggressive and sentimental, and it became an important part of her private and public mythos. Her biographers tellingly provide a view from the ‘watch-tower’ through the classical arch as their frontispiece, a decision warranted by contemporary publicity photos of Corelli leaning out of the window on the folly’s first floor. The ‘watch-tower’ thus envisioned Corelli as a heroine of romance, but it also furnished a window from which to wave to a global public.

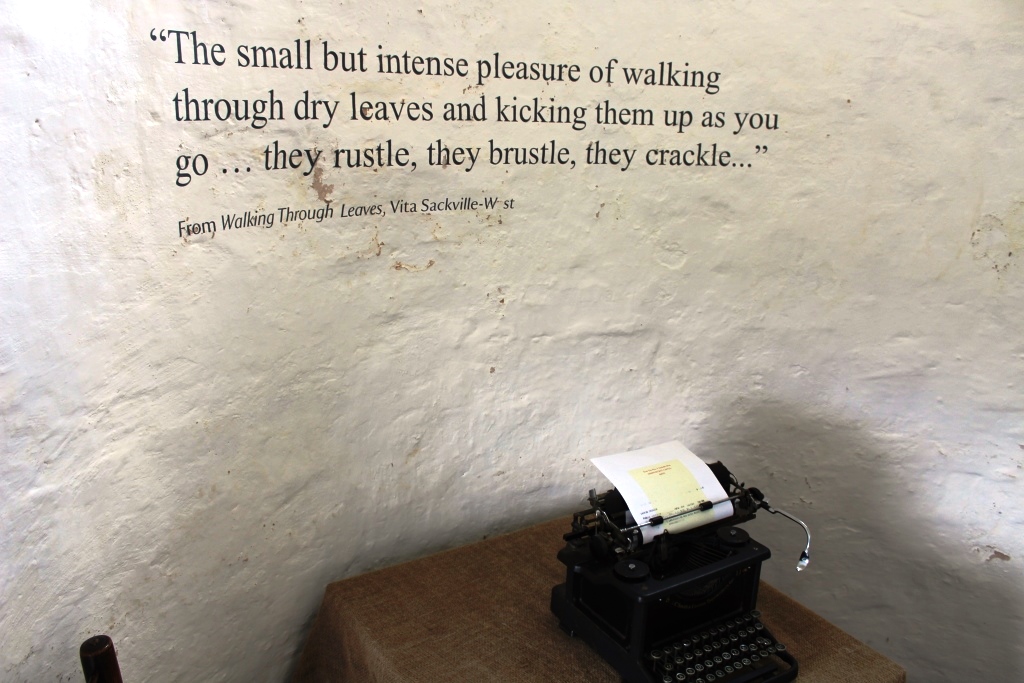

By contrast to Corelli’s garden-folly the most famous tower writing-space associated with a woman decisively turns away from house, garden and the larger landscape, folding in upon itself. In 1930 Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson bought the mutilated remains of a moated Elizabethan courtyard house set within a small estate. Here Sackville-West, poet, novelist, journalist and gardener, commandeered the most improbable looking building in the motley collection, what might once have been a platform from which to view the hunt in the deer-park, and was now entirely isolated. Within this, she made a writing-space at the centre of what would become the famous Sissinghurst Castle Garden. Her study on the first floor is now set up by the National Trust as she used it, high-windowed, curtained, lamp lit, and barred to all but very few visitors: as the interpretive caption notes ‘Vita allowed very few people into her sacrosanct space during her lifetime, including her two sons, this is why we do not allow access into this delicate room.’

In her account of discovering the property, Sackville-West herself characterised the tower as ‘Sleeping Beauty’s castle’. Her self-mythologising poem ‘Sissinghurst’ (1931), dedicated to her ex-lover Virginia Woolf who had just celebrated her as the androgynous protagonist of her novel Orlando (1928), was written in this study. In it she describes the tower as ‘Buried in time and sleep,/So drowsy, overgrown,/That here the moss is green upon the stone,/And lichen stains the keep.’ The paralysis of time allows for the growth of dream: ‘For here, where days and years have lost their number,/I let a plummet down in lieu of date,/And lose myself within a slumber…’ Sackville-West characterises herself as a counter-version of Tennyson’s Mariana and the Lady of Shalott, a lady in a moated grange who is not waiting for a lover, and who is not seduced into looking out of the window. Instead, she remains devoted to fragile illusion, living in reflection, mirror and trance: ‘I’ve sunk into an image, water-drown’d…/Illusive, fragile to a touch, remote/As no disturber of the mirrored trance/I move…’

For more on Marie Corelli’s garden-folly see https://www.open.ac.uk/blogs/literarytourist/?p=219