Post 2 Juliet’s tomb

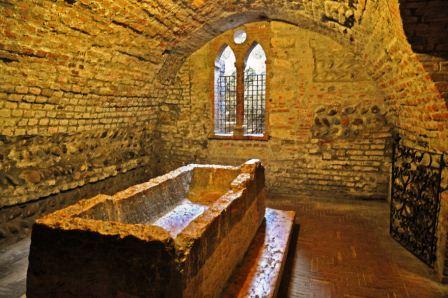

To Shakespeare’s ‘fair Verona’. I’ve been invited to speak on Shakespeare tourism as part of a conference on Romeo and Juliet. In between sessions, I hurry off to places that early nineteenth-century English travellers passing through Verona put on the top of their must-see lists. Byron, Mary Shelley, Chateaubriand, Heine, Kotzebue, all came to see what was reputed to be the original Juliet’s tomb. In 1816, when Byron saw it, it was lying derelict in the garden of an abandoned monastery; later in the century it was moved under a portico and tidied up; and in the nineteen-thirties it was housed in a crypt adapted for it, mostly to make it look more like Juliet’s tomb in Cukor’s film. Nowadays you reach it through an elaborate installation of statues, busts, sculptures, paintings and plaques bearing quotations associated with the play and its author. This is what it looks like today, installed in an atmospheric crypt.

This tomb seems to have been invented in ravaged post-Napoleonic Europe almost entirely to please wealthy English travellers. There had been some tradition in the eighteenth century of the tomb of Juliet Capulet, but it had certainly disappeared. Yet the poet Samuel Rogers, who had hurried over onto the continent in 1814, fleeing back home after Napoleon’s escape from Elba, records viewing ‘with the eye of faith Juliet’s stone coffin, the niche for her lamp, the spiracle for her respiration.’ By the early 1820s viewing it with ‘the eye of faith’ seems to have been very much the order of the day, and tourists were romantically inventive. ‘With what feelings of fond, and pensive melancholy did I approach that shrine sacred to hapless, blighted love’ mused the anonymous author of A Classical and Historical Tour through France, Switzerland, Italy in 1821 and 1822 (1824, 1826), before exerting himself in extensive Shakespearean quotation on the spot. He is one of the first to note ‘the impress made purposely in the stone for Juliet to recline her head’ (again if you look at the picture above you can just see the ‘pillow’) and reveals that there was by now a visitors’ book in which it was customary to write ‘effusions’. Rogers also remarked that the coffin was already being damaged by English relic-hunters. If you look at the picture above you can see that the sides have been chipped away. Chateaubriand, attending the Congress of Verona of 1822, said that the necklace and bracelets worn by Maria-Louise, Archduchess of Parma and widow of Napoleon, were made of the reddish stone of the sarcophagus. Valery wrote of a visit in the 1820s that ‘some illustrious foreigners and handsome ladies of Verona wear a small coffin of this same stone’ ; and in 1829, the traveller Maria Callcott remarked on meeting a gentleman, who, being ‘dans le gens romantique’, sported a fragment of the tomb set in a ring.

This habit was later satirised in The Struggles and Adventures of Christopher Tadpole (1848) in which the souvenir collection of a woman traveller, the silly and victimised Mrs Hamper, contained ‘all sorts of Juliet’s tombs from Verona, to supply all of which that have been made from the monument itself, the original must have been an entire quarry’. Although by mid-century the tomb was regarded as a fraud, tourists still seem to have gone in for sentimental self-staging. William Harrison Ainsworth retailed a story ‘of an English lady, who, being missed, was found half dead and in a state of ecstasy – in a white muslin morning dress and satin shoes – in the tomb itself’. The intention here is satiric— but it is much less clearly so in an 1846 report of an English male enthusiast laid at full length within the sarcophagus. These private rituals were matched by more consciously public ones; in 1887, a visitor reported the tomb’s inside as ‘strewn with visiting-cards – travellers from all parts of the world paying this tribute of respect to the memory of the unfortunate girl-bride’. There were even photographs amongst the litter, including one of a young lady superscribed with a message of sympathy for Juliet. This is the ancestor of the famous letter first left at the tomb in 1937. Relic-taking is here replaced by message-leaving – but the impulse is very similar – a public display of feeling and empathy.

When I went (in the rain) Juliet’s tomb was virtually deserted. Nothing could more strikingly exemplify the difference between nineteenth-century and modern enthusiasm. The site is covered in graffiti, and you can still get married in the chapel above the tomb, but there is a certain dereliction in the air. Perhaps the lovers’ death together is less erotic than once it was. Scattered about the site are various monuments and sculptures that meditate upon Shakespeare and his works – an indigestible mix of older ideas, like the 1902 bust of Shakespeare, and very modern takes, like the vast double metal heart, made by the designer of Juliet’s desk. Most aggressive of all is a huge sculpture shipped over from China depicting what purports to be ‘the Chinese Romeo and Juliet’ that dominates the walkway to the tomb. It seems strange that Romeo and Juliet should have become some of the world’s most famous and influential people who ever lived, stranger still that they have become patron saints of marriage, given that the whole affair was more of a disastrous one-night stand.