Post 8 Travels in the Library

July 2013 These last two weeks, I have been hunkered down in the Upper Reading Room of the Bodleian Library in Oxford, reading. To my right, coat, bag, phone, and a pile of eighteenth century calf-bound books stashed in grey cardboard boxes. These are the travel-books that have never done much travelling themselves. Instead of falling to pieces in a long-dead traveller’s pocket in some hotel or inn, they are the one copy of that book that a copyright library like the Bodley is entitled to.

In their pages I have been travelling across Europe at break-neck speed. I have left from Dover by packet and hurried to Dieppe, taken carriage or post-horse through Rouen to Paris, paused to sample Paris society before taking the road again for Nice or Marseilles, packed again to travel across the Jura and so arrived in Turin and then onwards; I have travelled to Plymouth, taken ship via Biscay and been landed sick in Lisbon or Leghorn; I have been ferried to Brussels and then been rowed down the Rhone into the heart of Switzerland, paused in Geneva, made a series of excursions around the Alps, hurried over Napoleon’s new road through the Simplon pass and so down to Milan and then through the Veneto to the sleazy delights of Venice. I have travelled by packet, row-boat, cabriolet, calèche, char-a-banc, post-chaise, private carriage, cart, by donkey and on foot. I have viewed antiquities, art, churches, literature, landscape beauties, geology, local customs, and considered the political and religious state of the nations. I have travelled with poets young and old, bad and good, with a honeymooning wife and a middle-aged Oxford don, with an engagingly silly young gentleman pedestrian and with milord’s six carriage entourage complete with library and menagerie, with intrepid women and invalid men. I have travelled with some of the best company the age could offer – with Byron, Shelley, Mary Shelley, Rousseau, Madame de Staël, William Beckford, Lady Sydney Morgan, Humphrey Davy, Chateaubriand and many others.

The object of this odd and enthralling exercise is to write a conference paper to an unnervingly tight deadline. I am trying to describe how travel and tourism lived out and inscribed a global literary culture across the European map. My interest spans from the late 1780s through to the 1830s, but this paper is about the years immediately following Waterloo, when English travellers flooded into continental Europe and conducted a stock-take on the wreckage of what was left after a world war. I’ve been trying to work out what were the must-see literary locations for the post-Waterloo traveller. What emerges looks something like this:

Literary Locations: The Top Ten

- Voltaire’s chateau, Ferney

- Locations associated with Rousseau’s novel at Clarens and Vevey, on the shores of Lake Geneva

- Rousseau’s houses at Motiers, and Ile St Pierre in Lake Bienne

- Gibbon’s summerhouse, Lausanne

- Petrarch’s house, Vaucluse

- Petrarch’s house, Arquà

- Juliet’s tomb,Verona

- Tasso’s cell, Ferrara

- Ariosto’s armchair, Ferrara

10. Virgil’s tomb, near Naples

11. Loch Katrine, associated with Walter Scott’s poem The Lady of the Lake

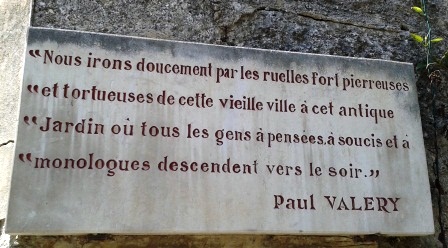

But there were, of course, others. One of the more surprising is the so-called ‘tomb of Narcissa’, the poet Edward Young’s daughter in what are now the botanic gardens in Montpellier. Buried there at the dead of night because she was a protestant, the young woman’s grave became a paradigmatic romantic location, as the many plaques there, quoting Young, Valery and Gide on their visits now attest.

As a risky generalization, what gets romantic tourists going is solitary figures expressing extreme and irresolvable emotion in extreme settings. These figures may be historical or fictional; what is essential is that they should have a first person voice, which must place them in the setting and suffuse it with ‘associations’. The tourist then revives these within their memory, and the travel-writer reiterates this process by selective quotation. The figure that links the most important sites is imprisonment or exile.

So much for the basic academic enquiry I’m working out. Round the edges of it, though, all these travellers come alive – the exasperatingly silly, the depressingly practical, the man of the world, the crashing bore – no doubt all dragged at the heels of the same long-suffering post-horses. What discomforts, miseries and adventures these privileged travellers endured – the bride who found herself giving birth at Como on her extended honeymoon and a few days later having her new baby baptised in the snows of the Simplon pass because there was an English clergyman passing through; the undergraduate who thought it would be reasonable to walk the St Bernard Pass bare-legged one night in December; the woman whose daughter sickened, died, and was buried in a matter of hours at Rome; the callow lawyer of ‘military height’ who narrowly escaped enlistment into the Prussian army!